Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (59 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

identify the locations and functions of the main lymphatic vessels of the body.

Lymph

Lymph is a clear watery fluid, similar in composition to plasma, with the important exception of plasma proteins, and identical in composition to interstitial fluid. Lymph transports the plasma proteins that seep out of the capillary beds back to the bloodstream. It also carries away larger particles, e.g. bacteria and cell debris from damaged tissues, which can then be filtered out and destroyed by the lymph nodes. Lymph contains lymphocytes, which circulate in the lymphatic system allowing them to patrol the different regions of the body. In the lacteals of the small intestine, fats absorbed into the lymphatics give the lymph (now called

chyle

), a milky appearance.

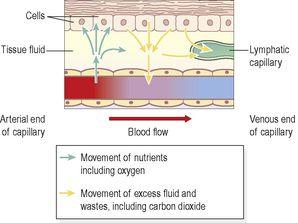

Lymph capillaries

These originate as blind-end tubes in the interstitial spaces (

Fig. 6.2

). They have the same structure as blood capillaries, i.e. a single layer of endothelial cells, but their walls are more permeable to all interstitial fluid constituents, including proteins and cell debris. The tiny capillaries join up to form larger lymph vessels.

Figure 6.2

The origin of a lymph capillary.

Nearly all tissues have a network of lymphatic vessels, important exceptions being the central nervous system, the cornea of the eye, the bones and the most superficial layers of the skin.

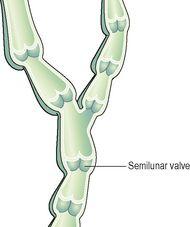

Larger lymph vessels

Lymph vessels are often found running alongside the arteries and veins serving the area. Their walls are about the same thickness as those of small veins and have the same layers of tissue, i.e. a fibrous covering, a middle layer of smooth muscle and elastic tissue and an inner lining of endothelium. Like veins, lymph vessels have numerous cup-shaped valves to ensure that lymph flows in a one-way system towards the thorax (

Fig. 6.3

). There is no ‘pump’, like the heart, involved in the onward movement of lymph, but the muscle layer in the walls of the large lymph vessels has an intrinsic ability to contract rhythmically (the lymphatic pump).

Figure 6.3

A lymph vessel cut open to show valves.

In addition, lymph vessels are compressed by activity in adjacent structures, such as contraction of muscles and the regular pulsation of large arteries. This ‘milking’ action on the lymph vessel wall helps to push lymph along.

Lymph vessels become larger as they join together, eventually forming two large ducts, the

thoracic duct

and

right lymphatic duct

, which empty lymph into the subclavian veins.

Thoracic duct

This duct begins at the

cisterna chyli

, which is a dilated lymph channel situated in front of the bodies of the first two lumbar vertebrae. The duct is about 40 cm long and opens into the left subclavian vein in the root of the neck. It drains lymph from both legs, the pelvic and abdominal cavities, the left half of the thorax, head and neck and the left arm (

Fig. 6.1A and B

).

Right lymphatic duct

This is a dilated lymph vessel about 1 cm long. It lies in the root of the neck and opens into the right subclavian vein. It drains lymph from the right half of the thorax, head and neck and the right arm (

Fig. 6.1A and B

).

Lymphatic organs and tissues

Learning outcomes

After studying this section, you should be able to:

compare and contrast the structure and functions of a typical lymph node with that of the spleen

describe the location, structure and function of the thymus gland

describe the location, structure and function of mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue (MALT).

Lymph nodes