Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (169 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Proliferation

This begins as granulation tissue, consisting of capillary buds, phagocytes and fibroblasts, and develops at the base of the cavity. It grows towards the surface, probably stimulated by macrophages. Phagocytes in the plentiful blood supply tend to prevent infection of the wound by ingesting bacteria after separation of the slough. Some fibroblasts in the wound develop a limited ability to contract, reducing the size of the wound and healing time. When granulation tissue reaches the level of the dermis, epithelial cells at the edges proliferate and grow towards the centre.

Maturation

This occurs by

fibrosis

(see below), in which scar tissue replaces granulation tissue, usually over several months until the full thickness of the skin is restored. Scar tissue is shiny and does not contain sweat glands, hair follicles or sebaceous glands.

Fibrosis (scar formation)

Fibrous tissue is formed during healing by secondary intention, e.g. following chronic inflammation (

p. 369

), persistent ischaemia, suppuration or large-scale trauma. The process begins with formation of granulation tissue, then, over time, the new capillaries and inflammatory material are removed leaving only the collagen fibres secreted by the fibroblasts. Fibrous tissue may have long-lasting damaging effects.

Adhesions

These consist of fibrous tissue, which causes adjacent structures to stick together and may limit movement, e.g. between the layers of pleura, preventing inflation of the lungs or between loops of bowel, interfering with peristalsis.

Fibrosis of infarcts

Blockage of a vessel by a thrombus or an embolus causes an infarction (

p. 113

). Fibrosis of one large infarct or of numerous small infarcts may follow, leading to varying degrees of organ dysfunction, e.g. in heart, brain, kidneys, liver.

Tissue shrinkage

This occurs as fibrous tissue ages. The effects depend on the site and extent of the fibrosis, e.g.:

•

small tubes, such as blood vessels, air passages, ureters, the urethra and ducts of glands may become narrow or obstructed and lose their elasticity

•

contractures (bands of shrunken fibrous tissue) may extend across joints, e.g. in a limb or digit there may be limitation of movement or, following burns of the neck, the head may be pulled to one side.

Complications of wound healing

The effects of adhesions, fibrosis of infarcts and tissue shrinkage are described above.

Infection

This arises from microbial contamination, usually by bacteria, and results in formation of pus (

suppuration

).

Pus consists of dead phagocytes, dead cells, cell debris, fibrin, inflammatory exudate and living and dead microbes. The most common pyogenic (pus-forming) pathogens are

Staphylococcus aureus

and

Streptococcus pyogenes

. Small amounts of pus form

boils

and larger amounts form

abscesses

.

S. aureus

produces the enzyme coagulase, which converts fibrinogen to fibrin, localising the pus.

S. pyogenes

produces toxins that break down tissue, causing spreading infection. Healing, following pus formation, is by secondary intention (see above).

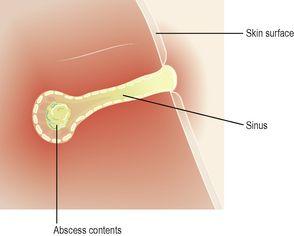

Superficial abscesses

tend to rupture and discharge pus through the skin. Healing is usually complete unless tissue damage is extensive.

Deep abscesses

may have a variety of outcomes. There may be:

•

early rupture with complete discharge of pus on to the surface, followed by healing

•

rupture and limited discharge of pus on to the surface, followed by the development of a chronic abscess with an infected open channel or

sinus

(

Fig. 14.8

)

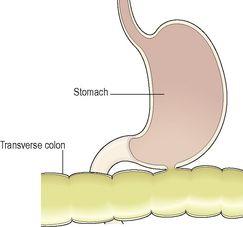

•

rupture and discharge of pus into an adjacent organ or cavity, forming an infected channel open at both ends or

fistula

(

Fig. 14.9

)

•

eventual removal of pus by phagocytes, followed by healing

•

enclosure of pus by fibrous tissue that may become calcified, harbouring live organisms which may become a source of future infection, e.g. tuberculosis (

p. 261

)

•

formation of adhesions (see above) between adjacent membranes, e.g. pleura, peritoneum

•

shrinkage of fibrous tissue as it ages, which may reduce the lumen or obstruct a tube, e.g. oesophagus, bowel, blood vessel.

Figure 14.8

Sinus between an abscess and the body surface.

Figure 14.9

Fistula between the stomach and the colon.

Disorders of the skin

Learning outcomes

After studying this section you should be able to:

list the causes of diseases in this section

explain the pathological features and effects of common skin conditions.

Infections

Viral infections

Human papilloma virus (HPV)

This causes

warts

or

veruccas

that are spread by direct contact, e.g. from another lesion, or another infected individual. There is proliferation of the epidermis and development of a small firm growth. Common sites are the hands, the face and soles of the feet.

Herpes viruses

Chickenpox and shingles (

p. 177

) are caused by the herpes zoster virus. Other herpes viruses cause

cold sores

(HSV1) and

genital herpes

(HSV2). The latter cause genital warts affecting the genitalia and/or anus and are spread by direct contact during sexual intercourse.

Bacterial infections

Impetigo

This is a highly infectious condition commonly caused by

Staphylococcus aureus

. Superficial pustules develop, usually round the nose and mouth. It is spread by direct contact and affects mainly children and immunosuppressed individuals. When caused by

Streptococcus pyogenes

(group A β-haemolytic streptococcus) the infection may be complicated, a few weeks later, by an immune reaction causing glomerulonephritis (

p. 343

).

Cellulitis

This is a spreading infection caused by some anaerobic microbes including

Streptococcus pyogenes

or

Clostridium perfringens

. The spread of infection is facilitated by the formation of enzymes that break down the connective tissue that normally isolates an area of inflammation. The microbes enter the body through a break in the skin. If untreated, the microbes may enter the blood causing septicaemia. In severe cases

necrotising fasciitis

may occur. There is oedema and necrosis of subcutaneous tissue that usually includes the fascia in the affected area.

Fungal infections

Ringworm and tinea pedis

These are superficial infections of the skin. In ringworm there is an outward spreading ring of inflammation. It most commonly affects the scalp and is found in cattle from which infection is spread. Tinea pedis (athlete’s foot) affects the area between the toes. Both infections are spread by direct contact.

Non-infective inflammatory conditions

Dermatitis (eczema)

Dermatitis is a common inflammatory skin condition that may be either acute or chronic. In acute dermatitis there is redness, swelling and exudation of serous fluid usually accompanied by

pruritus

(itching). This is often followed by crusting and scaling. If the condition becomes chronic, the skin thickens and may become leathery due to long-term scratching. Scratching may cause infection.