Roosevelt (80 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

The digitalis seemed to bring good results within three days. When Bruenn examined his patient on April 3, 1944, Roosevelt had had a refreshing ten hours’ sleep, his color was good, his lungs entirely clear, and there was no dyspnea on lying flat. The systolic murmur persisted, however, and his blood pressure was still disturbing. He continued to improve during the following days, but Bruenn and his colleagues decided that he needed a real vacation. The President readily agreed to take a long rest in the sun at Bernard Baruch’s plantation, “Hobcaw,” in South Carolina.

The cardinal issue during these alarming days was who should tell the President about his condition, and in what manner? The doctors agreed that he should be given the full facts, if only to gain his co-operation. But who would tell him? It was soon clear that the President himself would not raise the question; not once did he ask why he had to have the examination or take drugs or get more rest. He simply followed the doctors’ recommendations to the extent he could and left the matter there. Bruenn did not feel it his duty to inform the President; he was only a lieutenant commander and was a newcomer to the White House. Everyone evidently assumed that McIntire had the responsibility and would exercise it, but there is no indication that he did. Perhaps he lacked sufficient confidence in his own capacity to pass on such portentous findings to the President, especially if he should be asked difficult questions. Perhaps he sensed that the President would neither accept the significance of the findings nor act on them. Perhaps he realized how fatalistic the President was, or perhaps he realized that no matter how well grounded the findings there was a heavy psychological and political element in the situation, and that a President—especially one with Roosevelt’s determination—could not be advised as

easily or authoritatively as the ordinary patient. Or perhaps, after all his rosy prognoses of the past, he was simply too timid.

So Roosevelt went off to Hobcaw Barony not knowing that he was suffering from anything more than bronchitis, or the flu. He never asked what were the little green tablets—the digitalis—that he was taking. He wrote to Hopkins that he had had a really grand time there—“slept twelve hours out of the twenty-four, sat in the sun, never lost my temper, and decided to let the world go hang. The interesting thing is that the world didn’t hang.” He had pleasant visitors—members of his family, and Lucy Rutherfurd. He claimed that he had cut down his drinks to one and a half cocktails per evening and nothing more, “not one complimentary highball or nightcap,” and that he had cut his cigarettes down from twenty or thirty a day to five or six. “Luckily they still taste rotten but it can be done.” The President did experience a painful gall bladder attack at Hobcaw, but medication relieved the pain and there were no cardiac symptoms.

So it was not really a matter of work. He was tired, Miss Perkins remembered later, and he could not bear to be tired. Grace Tully still worried about the more pronounced tremble of his hands as he lit a cigarette, the dark circles that no longer ever seemed to fade from around his eyes, the slump in his shoulders. Watching Roosevelt at a press conference in March, Allen Drury felt that “subdued” was the only word for the man. The well-known gestures—the quick laugh, the upflung head, the open smile, the intent, open-mouthed, expressionless look when he was listening—all were there, just as they had been in numberless newsreels and photographs. But underneath, Drury detected a certain lifelessness, a certain preoccupation, a tired impatience—whether from work or political opposition, or from age or ill-health, Drury could not tell.

On his Washington stopovers James Roosevelt noted that his father was doing little things—autographing books and digging mementos out of old trunks and boxes for his children and grandchildren—as though he had some feeling of time closing in. Still, the old buoyancy was there, even if it took longer to show. Washington would twitter with gossip that the President was dead or dying, and then he would return from the South or from Hyde Park, refreshed, appearing a bit thin but radiant and vigorous. Visitors kept remarking on how wasted the President’s face seemed, but the main reason for his changed appearance was his determination to lose weight—and his success in dropping from 188 pounds to about 165.

Nothing stimulated him more than memories of old times. When Eleanor was told in Curacao that “Lieutenant” Roosevelt had visited there on an American warship and had been given a goat

as a mascot for his ship, she asked her husband, “What have you been holding out on me all these years?”

“I have an alibi,” the President wrote in a memo to her. “The only time I was ever in Curacao in my life was in 1904 when I went through the West Indies on a Hamburg-American Line ‘yacht.’ I was accompanied by and thoroughly chaperoned by my maternal parent.

“I was never given a goat—neither did anyone get my goat!

“This looks to me like a German plot!”

In his diary Stimson was still railing at the President’s “one-man government,” which helped produce “this madhouse of Washington.” In fact, his chief was running the White House much as he had in prewar days, while all around him were rising the huge bureaucratic structures of defense and welfare that would characterize the capital for decades to come.

The apex of the huge structures was the tiny west wing of the White House. Here the old hands, including Steve Early and Pa Watson, served and protected the President. Executive clerks Maurice Latta and William Hopkins sought to keep some control over the documents and messages that flooded into the White House—no easy job given Roosevelt’s distaste for set communications channels. The White House office had already begun to spill over into the old State Department Building across the way; administrative assistants—Jonathan Daniels, Lowell Mellett, Lauchlin Currie, David K. Niles, and others—occupied on the second floor a row of offices that they called “Death Row” because of the turnover. The President obtained Blair House, across the street, for putting up distinguished guests. Rosenman was still in charge of the speech-writing team, but he had no team, because Hopkins was in the Mayo Clinic and Sherwood was in London as head of the Overseas Branch of OWI.

Over in the east wing, which was in the final stages of building, Byrnes ran an even smaller shop than Roosevelt’s. In a clutter of tiny offices and partitioned cubbyholes—for a time the news ticker was in the men’s room—a small staff struggled with the tide of problems relentlessly streaming in from the civilian agencies struggling for funds, authority, manpower, and recognition. Ben Cohen, as incisive and unpretentious as ever, served as his legal adviser; “special adviser” Baruch offered wise, opinionated counsel; Samuel Lubell and a handful of others made up the rest of the full-time staff. Byrnes set up a War Mobilization Committee composed of Stimson, Nelson, and other top civilians. Roosevelt

occasionally presided over its meetings—it was the nearest thing he ever had to a war cabinet—but like most of the White House committees it dwindled into innocuous desuetude.

Crowded also into the east wing was Admiral Leahy, with a staff that never numbered more than two or three civilian secretaries and a couple of aides. Unlike Byrnes, he spurned the notion of having a public-relations man, on the grounds that his chief should do all the talking and was better at it anyway. As Roosevelt’s personal Chief of Staff, Leahy presided over meetings of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, prepared its agenda, and signed its major decisions, but he did not exert strong leadership on the committee and recognized that important decisions were often made between Roosevelt and individual members of it, especially Marshall. Behind the JCS were banked its supporting agencies: the Joint Deputy Chiefs of Staff, Joint Secretariat, Joint Staff Planners, with its own Joint War Plans Committee, Joint Intelligence Committee, and a host of others.

The third leg supporting the administrative tripod of the White House was the Bureau of the Budget, also located in the old State Department Building. Under Harold Smith’s gifted leadership the bureau had moved far beyond its traditional budgetary responsibility and was making ambitious efforts to plan, co-ordinate, and review the whole war administration. With its special access to the west wing and with the talents of men like Wayne Coy, Donald Stone, and Stuart Rice, the Budget Bureau had become the President biggest single staff resource.

On paper, in form, on an organization chart it all looked so logical—the Chief Executive at the top of the administrative apex, his three “assistant presidents” or chiefs of staff just below him, and then the lines of control and responsibility radiating out to the great bureaucratic workshops along Pennsylvania Avenue and the Mall. In fact, Roosevelt was carrying on the old Rooseveltian tradition of administrative juggling and disorganization. He was no more able in 1944 than in 1940 or 1934 to work through one chief of staff. He had not three, but at least a dozen, “assistant presidents,” including Marshall, the more influential Cabinet members, especially Hull and Stimson, war-agency czars Nelson, McNutt, Land, and others. Despite Leahy’s and Byrnes’s efforts, co-ordination among the “assistant presidents” was sometimes weak. Byrnes and Smith jousted with each other with icy politeness. It was not always clear whether Marshall or Stimson should report to the President on a military matter.

Roosevelt’s penchant for secrecy within the administration compounded the whole problem. Even such a primitive matter as communication was not always certain; occasionally messages to

Roosevelt were delayed days and even weeks, and generals and admirals learned about a vital White House decision first from the British. Marshall sometimes was unsure which version of presidential statements at Cabinet meetings was correct. And he complained to Byrnes that the JCS had to wait a day or two before learning of important White House decisions.

Hopkins, the only man who had ever really served as assistant president or as an over-all chief of staff, was sorely missed. He was restless to come back but finally aware of his condition. When T. V. Soong asked him for aid on a matter, Hopkins balked. “Tell them I’m sick.” But the President seemed in no hurry to have Hopkins back. He ordered him to stay away from the White House until mid-June at the earliest. If he returned before that, Roosevelt warned, he would be extremely unpopular in Washington, “with the exception of Cissy Patterson who wants to kill you off as soon as possible—just as she does me….

“Tell Louise to use the old-fashioned hatpin if you don’t behave!”

As Roosevelt’s reference to Cissy Patterson suggested, the hostilities between the White House and part of the press continued through the war. Administration officials held confidential “backgrounders” with favored members of the press—columnist Raymond Clapper, Marquis Childs, of the St. Louis

Post-Dispatch,

Turner Catledge, of the New York

Times,

and a few others. The anti-Roosevelt newspapers retaliated by publishing “secret” war information. The President could do little but complain at his press conferences about irresponsible columnists and commentators.

It did seem in early 1944, though, that he was at last bringing to book a group of radical rightists whom he considered guilty of seditious conduct. For weeks he had prodded Biddle at Cabinet meetings: “When are you going to indict the seditionists?” Finally, Biddle did so, but the preliminaries stretched out over months. He put a group of thirty on trial in Federal District Court in Washington. It seemed like a grand rally of all the fanatic Roosevelt haters: Joseph E. McWilliams, head of the Christian Mobilizes, who liked to refer to Roosevelt as the “Jew King”; Mrs. Elizabeth Dilling, author of

The Red Network

; an erratic lady nicknamed “T.N.T.” who delighted photographers with her stiff-armed Nazi salutes; James True, said to have received Patent No. 2,026,077 for a “Kike Killer,” a short rounded club made also in a smaller size for ladies; Lawrence Dennis, philosopher of fascism; and others ranging from the dotty to the desperate. The defendants were charged with conspiring to overthrow the government in favor of a Nazi dictatorship and stating that the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was deliberately invited by Roosevelt and his gang; that the American government was controlled by Communists, international Jews, and plutocrats; that the Axis cause was the cause of morality and justice. The trial got under way amid histrionics but dwindled into endless legalisms and obstructions; it lasted over seven months; the judge died before its conclusion; no retrial was held, and in the end the indictment was ingloriously dismissed. The trial did serve to muzzle “seditious” propaganda, but it also revealed Roosevelt as a better Jeffersonian in principle than in practice.

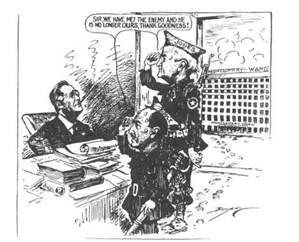

May 11, 1944, C. K. Berryman, courtesy of the Washington (D.C.)

Star

Perhaps the most bitter anti-Rooseveltian in the spring of 1944 was no seditionist, but Sewell Avery, head of the huge mail-order house Montgomery Ward. For many months Avery had been defying the War Labor Board by refusing to negotiate with the CIO union that had won representation rights. When the union called a strike the President ordered the men to return to work and the company to follow the Labor Board’s orders and recognize the union. Avery refused. Normally the War Department would have taken over the plant, but knowing that Stimson was keenly opposed to seizure of a nondefense industry and perhaps glad for a chance to put Jesse Jones on the spot, Roosevelt ordered the Secretary of Commerce to seize and operate the Chicago plant. Jones

promptly turned the job over to his Undersecretary, Wayne Taylor, himself a wealthy Chicago businessman. Prodded by Byrnes to go to Chicago and expedite the seizure, Attorney General Biddle flew out, occupied Avery’s office, and asked for Avery’s co-operation. When Avery refused, saying “to hell with the government,” he ordered him taken out.