Roosevelt (75 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

“There is terrific tension on the Hill,” Budget Director Smith noted. “People who have been friends for years are doing the most erratic things.” A leading politician said privately: “I haven’t an ounce of confidence in anything that Roosevelt does. I wouldn’t believe anything he said.”

Seldom had race feeling been so conspicuous in the capital. Indignation greeted the news that 16,000 “disloyal” Japanese had rioted at the Tule Lake concentration camp. The Senate killed a federal aid-to-education bill when Republicans adroitly hitched on an antidiscrimination provision. Railroad employers and unions alike defied an FEPC order barring discrimination against Negro firemen. Not since Reconstruction, the

Nation

observed, had sectional feeling run so high in the halls of Congress.

“The President has come back to his own Second Front,” Max Lerner wrote. “We shall need to build another bridge of fire, not to link in with our Allies but to unite us with ourselves, and to span the fissure within our own national will.”

The center of the storm seemed as calm as ever. He had got the impression on returning that there was a terrible mess in

Washington, the President observed mildly to the Cabinet. Nor did he betray any worry. “There he sat,” reported the

New Republic

’s TRB, “at his first press conference after his five weeks on tour-Churchill sick; inflation controls going all to pot; the Democratic party at sixes and sevens; a rail strike threatened; selfish goals sought by labor and farmers and business; ignoble motives imputed to every public act of every public man; the world a global mess—and there he sat, bland and affable, in his special chair, puffing imperturbably on an uptilted cigarette and welcoming old friends.”

Roosevelt was not as imperturbable as he appeared. He was entering the new year like a tightrope walker starting out over Niagara. Monumental questions were hanging in the balance—not only the war economy, his electoral standing with the voters, the cross-channel invasion, the invasion routes to Japan, but also his whole strategy of war and peace. He was following a precarious middle way. He was trying to establish close rapport with Russia and at the same time follow an Atlantic First strategy depending on the closest relations with the British. He was trying to help make China a great nation in war and peace while putting it far down the priority list of military aid and political influence. He was trying to establish a new and better League without alienating the isolationists. He was calling for freedom for all peoples but deferring to the British in India and the Moslems in the Near East. He was demanding unconditional surrender but dealing with Darlans and Badoglios.

He had said that “magnificent idealism” was not enough; neither was manipulation or expediency. How he balanced and interlinked the demands of his faith and the necessities of the moment would be the great test of Franklin Roosevelt in 1944.

After seeing soldiers stuck in lonely outposts in Iran and stretched out on hospital cots in Sicily, the President was indignant about the attitudes he found at home—complacent expectations of an early victory, isolationists spreading suspicion about the Allied nations, noisy minorities demanding special favors, profiteers, selfish political interests, and all the rest. He decided to declare war on these elements in his State of the Union message—indeed, to make a dramatic reassertion of American liberalism even at the height of war.

But first he indulged in one of those baffling sidesteps that often had accompanied, and camouflaged, a major Rooseveltian action. To a reporter who had tarried a bit after a press conference the Chief Executive had complained that he wished the press would not use that term “New Deal,” for there was no need of a New Deal

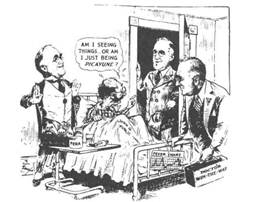

now. At the next press conference reporters pressed him for an explanation. The President assumed a casual air, as though it was all so obvious; some people, he said, just had to be told how to spell “cat.” He described how “Dr. New Deal” had treated the nation for a grave internal disorder with specific remedies. He quoted from a long list Rosenman had put together of New Deal programs. But after his recovery, he went on, the patient had a very bad accident—“on the seventh of December, he was in a pretty bad smashup.” So Dr. New Deal, who “didn’t know nothing” about legs and arms, called in his partner, “who was an orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Win-the-War.”

“Does that all add up to a fourth-term declaration?” a brash reporter asked.

“Oh, now, we are not talking about things like that now. You are getting picayune….”

“I don’t mean to be picayune,” the reporter went on, “but I am not clear about this parable. The New Deal, I thought, was dynamic, and I don’t know whether you mean that you had to leave off to win the war and then take up again the social program, or whether you think the patient is cured?”

The President answered with a confusing analogy of post-Civil

War policy. Then he insisted again: the 1933 program was a program to meet the problems of 1933. In time there would have to be a new program to meet new needs. “When the time comes…When the times comes.”

There’s an Odd Family Resemblance Among the Doctors

December 30, 1943, C. K. Berryman, courtesy of the Washington (D.C.)

Star

The creator of the New Deal had killed it, the conservative press exulted.

Two weeks later Roosevelt gave the most radical speech of his life. He chose his annual State of the Union message as the occasion. Early in January he had come down with the flu, but he labored over draft after draft while Rosenman and Sherwood sat by his bed. He had not recovered enough to deliver the message to Congress in person, but he insisted on giving it as a fireside chat in the evening for fear that the papers would not run the full text.

The President lashed out at “people who burrow through our Nation like unseeing moles…pests who swarm through the lobbies of Congress and the cocktail bars of Washington…bickering, self-seeking partisanship, stoppages of work, inflation, business as usual…the whining demands of selfish pressure groups who seek to feather their nests while young Americans are dying.”

Once again he asked Congress to adopt a strong stabilization program. He recommended:

“1. A realistic tax law—which will tax all unreasonable profits, both individual and corporate, and reduce the ultimate cost of the war to our sons and daughters….

“2. A continuation of the law for the renegotiation of war contracts—which will prevent exorbitant profits and assure fair prices to the Government….

“3. A cost of food law—which will enable the Government (a) to place a reasonable floor under the prices the farmer may expect for his production; and (b) to place a ceiling on the prices a consumer will have to pay for the food he buys….

“4. Early reenactment of the stabilization statute of October, 1942….We cannot have stabilization by wishful thinking. We must take positive action to maintain the integrity of the American dollar.

“5. A national service law—which, for the duration of the war, will prevent strikes, and, with certain appropriate exceptions, will make available for war production or for any other essential services every able-bodied adult in the Nation.”

Then came the climax of the address:

“It is our duty now to begin to lay the plans and determine the strategy for the winning of a lasting peace and the establishment of an American standard

of living higher than ever before known. We cannot be content, no matter how high that general standard of living may be, if some fraction of our people—whether it be one-third or one-fifth or one-tenth—is ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed, and insecure.

“This Republic had its beginning, and grew to its present strength, under the protection of certain inalienable political rights—among them the right of free speech, free press, free worship, trial by jury, freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures.

They

were our rights to life and liberty.

“As our Nation has grown in size and stature, however—as our industrial economy expanded—these political rights proved inadequate to assure us

equality in the pursuit of happiness.

“We have come to a clear realization of the fact that

true

individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. ‘Necessitous men

are not

free men.’ People who are hungry—people who are out of a job—are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.”

The President was now speaking with great deliberateness and emphasis. The italics were not in his text, but in his delivery.

“In our day these economic truths have become

accepted as self-evident.

We have accepted, so to speak, a

second Bill of Rights

under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all—regardless of station or race or creed.

“Among these are:

“The right to a useful and remunerative

job

in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the Nation;

“The right to earn enough to provide adequate

food

and

clothing

and

recreation;

“The right of farmers to raise and sell their products at a return which will give them and their family a decent living;

“The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by

monopolies

at home or abroad;

“The right of every

family

to a decent

home;

“The right to adequate

medical

care and the opportunity to

achieve

and

enjoy

good health;

“The right to adequate protection from the

economic

fears of old age and sickness and accident and unemployment;

“And finally, the right to a good

education.

“All

of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be

prepared

to move

forward,

in the

implementation

of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being….”

In its particulars the economic bill of rights was not very new. It was implicit in the whole sweep of Roosevelt’s programs and proposals during the past decade; it was Dr. New Deal himself suddenly called back into action. But never before had he stated

so flatly and boldly the economic rights of all Americans. And never before had he linked so explicitly the old bill of political rights against government to the new bill of economic rights to be achieved

through

government. For decades the fatal and false dichotomy—liberty

against

security, freedom

against

equality—had deranged American social thought and crippled the nation’s capacity to subdue depression and poverty. Now Roosevelt was asserting that individual political liberty and collective welfare were not only compatible, but they were mutually fortifying. No longer need Americans swallow the old simplistic equation the more government, the less liberty. The fresh ideas and policies of Theodore Roosevelt and of Robert La Follette, of Woodrow Wilson and of Al Smith, of the earlier Herbert Hoover and of George Norris, nurtured in days of muckraking and protest, evoked by depression, hardened in war, came to a clear statement in this speech of January 11, 1944.

And this appeal fell with a dull thud into the half-empty chambers of the United States Congress.

“He’s like a king trying to reduce the barons,” Senator Wheeler had cried out against Roosevelt in the early New Deal years. He himself was the baron of the Northwest; Huey Long, the baron of the South; Roosevelt had once been just a baron, too. Ten years later most of the old barons, including Wheeler himself, dominated the political life of Capitol Hill. But now they were less the lords of regions—except, always, the South—than masters of procedure, evokers of memories, voices of ideology—and contrivers of deadlock. Power holding on Capitol Hill had changed little since before Pearl Harbor. There was the ancient and ailing Carter Glass, who, with his protégé Harry Byrd, still ran the Virginia Democratic party; Gerald Nye, as forceful, shrewd, and fundamentally isolationist as ever; Bennett Champ Clark, rotund and forensic, a spokesman for veterans; the stocky, smooth-faced Robert La Follette, less isolationist than his father but wary of Roosevelt’s foreign commitments; Hiram Johnson, seventy-seven, a true baron of the West, a bit feeble now but still a commanding presence with his noble features and snow-white hair. There were a brace of ambitious Republicans: Robert Taft, already high in the Senate establishment for a first-termer, dry, competent, assured; Arthur Vandenberg, now midway in his long, troubled retreat from isolationism, looking both wise and naïve , with his owlish little features setting off a big round face; the handsome, towering Henry Cabot Lodge, grandson of the great isolationist and a living invocation of the battles of 1919, a soldier who would soon go off to the wars again. There was a handful of vigorous internationalists: Warren Austin, of Vermont, Joseph H. Ball, of Minnesota, Harold H. Burton, of Ohio. Many

an internationalist Democrat was there, too: Alben Barkley, Abe Murdock, of Utah, Theodore Green, James E. Murray, of Montana, Harry Truman, and others. But the Democrats were divided in war as in peace. Walter George, Kenneth McKellar, of Tennessee, Theodore G. Bilbo, of Mississippi, William B. Bankhead, of Alabama, E. D. (“Cotton Ed”) Smith, of South Carolina, and others were guardians of the South, lords of their committees, and as a group not dependably internationalist.