Resurrection Man (27 page)

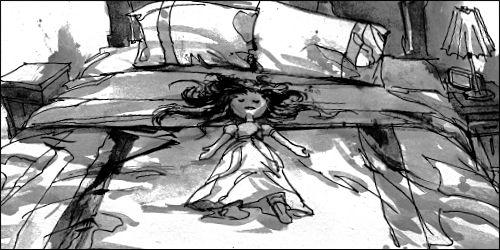

Laura picked through the little box of doll accessories and took out a tiny tortoise-shell comb. Slowly she drew it through the doll's long auburn hair. Of course, it wouldn't be like this with a real child. A real child wouldn't sit so long. A real child would kick and squirm. But still.

"I know you aren't really an angel. But I have to do something, you see. Mom really needs me now, but I'm no use to her like this. Obviously I could use a good strong dose of therapy, but I can't wait ten years to be functional again. I mean, God, what if Dante's right and he goes too? Who's going to hold this family together?"

Women, Laura thought. The women in the kitchen, chopping vegetables and crying.

Hair split heavily around the teeth of her toy comb like honey flowing, a river of it, stroke after stroke. Of course a real child might want to cut her hair short, or wear a baseball cap, or might be bald—you couldn't say. But still.

"So I need a, a charm, a ritual, anything. Something to ward her off, just for a few days. Something to lull my subconscious to sleep at least until the funeral is over. Then maybe I can find time. I mean, things can't go on like this; that's obvious."

But if she were sleeping, Laura thought, a real child might feel a little like this, resting in the bend of your arm. If she were sleeping, she might lean back like this while her mother combed her hair, one slow gentle stroke at a time. She would be warmer, of course. But still.

"I have to let go, I keep telling myself I have to let go—but it's easier said than done, you know?"

"Why?"

Sarah blinked. "Why what?"

"Why do you have to let go?" Gently Laura put the doll back on Sarah's dresser. Sarah was looking at her confusedly, like a woman' suddenly woken from a dream. "That's the trouble with you atheists," Laura continued irritably. "You can't stop thinking about yourselves. Me mine, I did this, my subconscious, I'm torturing myself, blah blah blah." Laura nudged the pair of sneakers with her foot. "This doesn't have anything to do with you.

Sarah stared blankly at her. "What?"

Laura could have kicked her.

"You just don't get it, do you?

There is a ghost in the house!

" Laura cried. "Don't keep treating her as if she were just a bad dream, just something you made up. She's

real

, Sarah. Every bit as real as you are." Laura pulled her best Annoyed Oriental face. "You round-eyes are so stupid sometimes."

Sarah blinked. "So, uh... Okay, she's real. So, what am I supposed to do?"

"Find out what she wants and give it to her, I expect. Isn't that how you placate ghosts in the West?"

"How should I know what she wants?"

"Don't be coy," Laura snapped. "It's perfectly obvious what she wants."

Sarah's shoulders stiffened, then slowly sagged. "Me," she whispered. "...How am I supposed to give her that, Laura? I've already failed my one chance."

Laura shrugged. "Just be open, that's my advice. She'll let you know if she can." Laura grunted, nudging the sneakers once more. "I get the feeling she'll get what she wants, sooner or later."

* * *

Portrait

The monster in these pictures (dozens and dozens of them) stands just under six feet tall. Its teeth are small. Its talons are blunt. It is not roaring. In fact it was actually wheezing as I took these shots, but you can't tell that just from looking.

The monster in these photographs does not wear my soul on an amulet around its neck. It does not even wear a tie. The monster in these pictures wears a shabby, good-natured suit of cheap raw silk, worn at the cuffs.

The monster no longer wears his hair slicked back. Once black and gleaming with brilliantine, it is now gray and thin. Once the monster's smile was made of razors; now there's nothing there but a set of cheap false teeth.

Because Jewel's friend Albert, Confidence, the man who destroyed my life, who drove my father to suicide and turned my mother against me: when I finally met him face to face, he wasn't a monster anymore. He was a balding portly bookseller in a part of town that had been fashionable once but wasn't now. He was a decent guy, embarrassed by what he had been, sweating a little and smiling a lot.

And all I could do was shoot him, again and again, round after round, frame after frame.

It wasn't the camera that gave up at last. But my hands aren't made of plastic and steel, and they started shaking.

My eyes aren't glass, after all. Tears crawled from them, and I couldn't see.

* * *

Glass is a liquid. Laura learned that in an undergraduate course, looking at pictures of a cathedral seven hundred years old where the glass had run like a melting candle, leaving the windows thin at the top, thick and marbled at the bottom.

That thought, and remembering the feel of the doll cradled in her arms, and remembering the way the Ratkay home had made her own beautiful apartment seem so lonely: all those images swimming together in the hour of Ch'ou gave Laura the answer to the problem of Mr. Hudson's solarium. With a grunt she rolled over in bed, grabbed the notebook and pencil she kept on the night table and scribbled: WINDOWS.

She would find the windows from Mr. Hudson's first home, from the home he grew up in as a boy. She would use them, the same glass (maybe even the same frames, she hadn't decided yet), to wall in the solarium. Because no summer sky could be as beautiful as the one that floated over you as a child: no blue so deep, no clouds so majestic. No shade sifted through whispering leaves could ever be so mysterious.

But she would bring that back for him, she and Mr. Ling. Together they would make a place not only for the great man Hudson had become, but for the small boy he would always be.

There are a lot of ghosts in all of us, she thought—and fell asleep.

D

EATH TWITCHES MY EAR. "

L

IVE," HE SAYS: "

I

AM COMING."

—V

IRGIL

CHAPTER

FOURTEEN

Portrait

I have several pictures of Father's funeral, but the one I come back to has no casket and no flowers. Dante grabbed my camera and took it when the funeral was over and we were back home, receiving condolence calls. It's a quick shot, badly framed: Mother's back is turned and I'm a little out of focus. Really, this is a picture of potato salad.

Every day I read

The New York Times

; it is the lens through which I view the world. It is full of war and poverty, atrocity and magic, glamours sinister and suspect. There is very little in it about potato salad. But standing in the parlor the day of Father's funeral, feeling the press of neighbors' hands, watching the dining table disappear under home-baked pies and tubs of coleslaw and casseroles wrapped in aluminum foil, that potato salad seemed more real than the atrocities in

The Times

: as real as Dante. As real as Father's loss.

I had not expected to stay all day in the front parlor, but I did. I didn't say much, mind you. Stood silent, mostly, watching our reflections meet and touch and pass in Grandfather Clock's glass chest. But it was warm and sad and human, and the quiet talk was better company than silence; soothing as the wind whispering in the maple leaves, or the ceaseless murmur the river makes, singing its long way softly to the endless ocean.

When we die, are we nothing but a body, a broken machine from which all meaning flies? Is a soul like smoke, given off by the body's combustion, that wavers and flees when the corpse grows cold?

I thought so once.

But meeting Albert, who had once been Jewel's Sending, showed me I didn't understand much about souls. About living. There was something more than mustard and potatoes in that potato salad. There was a meaning in that room that had everything to do with the food on the table, and with Father, and with all of us who had lost him. He was a part of all our lives, and he continued in us even after he was dead.

I remember Aunt Sophie watching me, all that afternoon. Her eyes were bloodshot from too many tears and cigarettes. Of course, she had just lost the last living member of her family. Edvard had died of fever, Leslie was shot down during the War. Her father she lost to a stroke in the summer of 1970, when the first minotaurs were crawling out of Watts. Her mother died three years later. Pendleton committed suicide, of course.

Me she lost—or threw away—the week I was born. Now little Anton had died too.

When I saw her watching me I expected something awful; a scene, threats, recriminations. That didn't happen. She just kept... looking at me. Once, I saw her talk to Sarah—a few phrases, nothing much—and afterwards I saw her slowly nod her head, looking at me. For a moment, I almost thought I saw something different in her eyes, a searching: as if, seeing me for the first time in thirty years, she had caught a glimpse of something she had never expected to see again.

Probably that was just my imagination.

That look doesn't show in this picture, of course. It's not really a very good photograph. When Dante gave it to me, I asked him why.

"Because you're in it," he said.

* * *

It was Friday, just after the funeral. The reception was still going on up at the house, but Dante was standing on the dock where he had cast his lure into the river a week before and reeled in a pike with a golden ring in its belly. He had not cried since his father collapsed beside the dining table. Mother had been devastated, Sarah's wide face blotched with tears; but Dante had not cried. Had felt very little, in fact. Puzzlement, maybe, that he was still alive.

He didn't think he had slept in the three days either, though it was difficult to remember. He felt dry and lifeless, not a man at all, but a leather puppet like the ones in Jewel's study.

Dante lived again the memory she had shown him: three years old, the feel of his cheek against the carpet, the dust motes dancing, the relentless ticks of Grandfather Clock.

We live in time.

Our dreams go on forever, and our ambitions, and our hopes, and the great play of our ideas reaches for eternity.

But we live in time. We die in time.

It was twilight, and winter was coming on with the cold blue dusk. Shadows flowed down from the steep wooded sides of the river valley and crept over the water. Dante remembered lying chest down on a sheet of buckling ice, screaming for Jet. The dark water pulling, pulling.