Resurrection Man (24 page)

Tock.

Three years old, he lay with his head on the carpet, already dying, watching the dust motes drift in the bar of sunshine and fall back into shadow.

Light and darkness.

Drift and fall.

Tick.

* * *

You begin to suspect what you already know.

Jewel's fingers tensed, tight as wire around his own.

I'll make an angel of you yet.

"Could Jewel be the one raising the ghosts?" Sarah asked.

Dante frowned. "I don't think so," he said slowly. "Jewel's specialty was Sendings. It's close, but not the same thing. She would fix on an image, a personality or an archetype maybe, and brood over it until it hatched into life. But those were things that existed in the twilight world."

"In the collective unconscious," Jet suggested.

"Right! Right. But this other thing. . . this raising the ghosts of actual people: I think that's me, somehow. There's some kind of, of field or something."

"The Lazarus Effect," Sarah intoned. "Great. Now we're trapped in an episode of

The Twilight Zone

."

"But what about Pendleton?" Jet said. "What about me?"

"Pendleton lost you to a Sending," Dante muttered, struggling to remember a memory that didn't belong to him. It was like trying to read small print in dim light while wearing glasses in the wrong prescription. "Jewel called him Albert, but his real name was Confidence. Jewel looked at Pendleton, and what she saw there—the hustler, the operator—was the germ of her Sending. But of course Confidence wasn't human: he was quick and sly and ruthless as Pendleton could never be."

Dante looked up, blinking. "He was an operator in the city for a time, but something changed. Last Jewel knew he was selling books out of a little shop on the east side called Bargain Books."

Jet fetched a copy of the Yellow Pages. He gave a queer little laugh. "Bargain Books: Let Us Cut a Deal for You." Jet copied down the address and then slowly closed the book. "Maybe I'll pay him a visit, sometime soon."

Dante felt weak relief wash through him. Almost done, thank God. He had almost done his duty to Jet. Lord, he was so tired. Maybe the growth inside him was stealing all his energy, as a fetus robs nutrients from its mother's body. Steady on, he told himself. It's almost over. "Do you want me along?"

Jet shook his head. "You've done everything I could have asked," he said slowly. "If I had known what it might cost you, I would never have started."

"You did know," Dante snapped impatiently. He remembered the press of his own ribs in his back as they wrestled in the grave on Three Hawk Island. The taste of dirt in his mouth, the taste of his own death. "You knew what was under the blanket, damn it. It's too late to say you're sorry now."

"Maybe." Jet closed his dark eyes. "But I am, Dante. I am sorry."

Dante felt Sarah's hand on his shoulder. "It will be okay," she said, hugging him. She sniffed and smiled. "Sorry I've been such a crybaby. But it will work out, D." She gave his shoulder another squeeze. "It will all be okay, somehow."

"Thanks," he said.

* * *

Sarah left, but at a look from Dante, Jet stayed. Dante sat on his bed, pulling on a fresh shirt and looking out his window. The last brittle leaves trembled on the poplars in the back yard. Farther on, the garden lay barren, blasted by an early frost. Farther still, the dark river. He had watched it all his life, running endlessly before his eyes and down the valley, into the shadows and beyond his sight, ending up God knew where. In the ocean, he supposed. Lost in the black immensity of the Atlantic.

"Why are we afraid of death?" he asked.

Jet scratched his jaw. "Seems like a reasonable thing to be afraid of."

"I mean, when you're up high you're afraid of falling. When you see a needle you're afraid of the pain. It's not like that with death though, is it?"

". . .No. I guess it isn't," said Jet. Jet always understood what Dante meant.

"It's not a matter of

consequences

," Dante said, frowning. "It just is. The one certain thing, stuck right in the middle of you, like your heart. The one thing you know. You fear it like, like. . ."

"Like you're supposed to fear God."

Dante nodded. From a lacquered box on his dresser he selected a new pair of cuff links, gold set with chips of polished jade. "It's the one thing," he said at last, watching the river. Smooth and dark, flowing out of sight, down to the ocean at last. "The only thing."

* * *

The one thing Dante knew he must do was talk to his father. He put it off—as he always put off everything unpleasant, he thought sourly to himself. In a fit of self- contempt he forced himself downstairs, only to find that Father was out delivering liniment for Jess Belton's rheumatism and a charm for Julie Gregson's little girl. Mother was taking advantage of the Thanksgiving Day sales to round up a good turkey, and Sarah had gone into the city. Only Aunt Sophie was left, puttering about the kitchen making one of her special cakes; the counters were cluttered with eggs and lemons and tubs of sour cream.

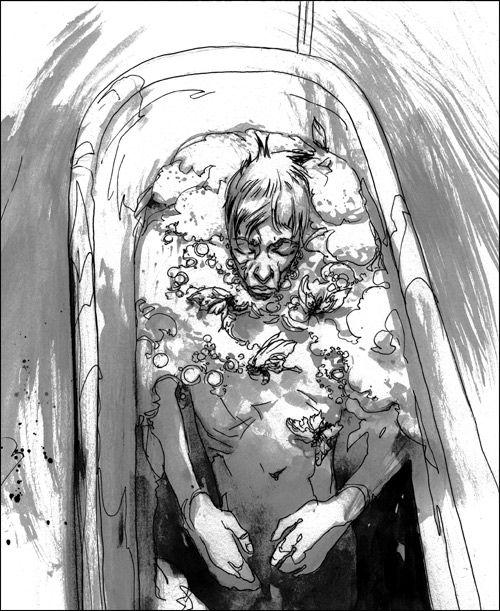

Frustrated and relieved at once, Dante slunk back upstairs. A bath: that's what he wanted. To loll in a big warm tub like an eight-year-old again.

Oops, he thought, running the water. Should have phoned the lab and left a message on the answering machine. Sorry—shan't be in again. About to die, don't you know. Cheerio. Oh, well; they'd figure it out soon enough.

Gratefully he lowered himself into the wonderfully hot water. Tense from days of near-panic, his muscles ached and sulked, particularly in his back and shoulders, but as the bath water closed over his chest he felt his whole body sigh with pleasure. He touched himself lightly on the abdomen, like a physician checking for appendicitis. He was almost sure he could feel a bulge.

Dante slid slowly under the water, letting it close over his face, blowing a stream of bubbles through his nose. It was wonderfully relaxing, warm as blood.

Three more days, he thought.

A butterfly tumbled from the hot water tap.

"Christ!" Dante swore, watching it heave and swamp, its crumpling wings quickly sodden. "Jesus, Jewel. Can't you do something less disgusting?"

An angel isn't a power, but a conduit for power. If what's inside you is a rose, you bring the rose forth. If it's a tumor, the tumor grows.

Dante fumbled for the soap. "Your definition makes angels sound a lot like loonies," he observed. "My sister tells a joke about that. 'Remember the Son of Sam?' she says. 'Killed twelve people because he said his dog told him to?—I mean, what kind of stupid reason is that? If your dog tells you to blow someone away with a .45 calibre handgun, what do you say? "BAD DOGGIE!"

Jewel laughed.

Good joke.

Making a face, Dante scooped up the dead butterfly on the back of a shampoo bottle. Leaning out of the tub, he shook it off into the toilet.

Jewel said,

Why three days?

"I made a bargain when we did the autopsy. One week to set things straight."

Made a bargain with whom?

"Just—just a bargain," Dante said, annoyed.

With yourself. You made a bargain with yourself.

"What if I did?"

You're the one who thinks you're going to die. You're the one waiting for it.

"So how did you die?" he asked moodily.

—I don't want to talk about that.

"Was it one of your Sendings? I bet it was. Just couldn't lay off, could you? What was it? A Sending of Nemesis, I bet."

Not a Sending.

Something quite different from Dante shuddered deep within his body.

"You should have let it lie, whatever it was."

Yes.

But free will is for humans, not angels. An angel's greatness is giving way to Greatness. The greater the angel, the less freedom she has. The more she is constrained by the powers around her.

The light went dim in Jewel's study (deep inside him). No longer sitting composedly behind the desk, Jewel walked nervously around her chamber, running her fingers over the back of a favorite book or touching, lightly, a certain mask, as if searching for the reassurance of familiar things.

A wizard tries to control magic,

she said.

An angel is its channel, its riverbed.

She turned on him.

It's not just human dreams—get it? Not just our fancies, our whimsies. It's real. That's what you figure out,

she murmured.

And— (with difficulty) and the things we see there are real.

"Like the Sendings."

She shook her head.

Only partly. Sendings need us. We find them, we bring them into the light. But there are other things too. . . . Chu never touched them. Aster and her crew never looked. They didn't dare, even when I told them. They couldn't bear to hold their eyes open. But last year for the first time I touched something that could walk into the world of its own accord, and walk back again.

She shuddered.

You know what you call that, don't you?

she asked, with a small, frightened laugh. Stopping before her desk, she stared at a doll sitting on it, a dark-eyed doll with human hair. The doll stared back with wide, watchful eyes.

Under its gaze, Jewel's lace gloves began to twitch and flutter, dissolving into a mass of gray crawling bodies.

You call that a god.

Dante caught his father in the study after lunch. "Do you have a minute?"

Sitting at his desk, Dr. Ratkay looked around in surprise. "Well, actually—"

"It's important."

Dr. Ratkay squinted, sighed, nodded. Dante came in.

We do look alike, he thought. When did that happen? If I went and looked through Mom's photo albums, what sort of man would I find standing over my cradle?

Slowly Dr. Ratkay swiveled in his chair to face his son. "Well?"

Dante took a deep breath. " 'Those whom God wishes to destroy, he first makes mad—' I'm going to die, Dad." He cut off his father's protest. "I'm going to die very soon, and I want you to promise you won't cut me open. No autopsy, no embalming, no . . . tampering."

Dr. Ratkay settled back in his chair, looking carefully at his son. He seemed small; much smaller than Dante remembered him. The heavy chair before his desk was too big for him now. Dr. Ratkay fixed himself a pipe, his fingers much slower and more precise than usual, as if the least mistake could cut an organ or sever an artery.

"I interned as a pathologist," he murmured at last. "You knew that, I suppose. Did I ever tell you why I came back here to be a GP instead?"

Dante shook his head, wondering at it for the first time. Why had Anton Ratkay come back, a sharp young medical man with a brand new degree? Why come back to his parents' house, to the sickly smell of his mother's lingering death? (The fat old woman tugging at Dante's sleeves, her stringy white hair; her soft bed a trap, like quicksand.) He remembered Sally Chen in her nursing home, tearing pictures of herself into tiny pieces, squares of color so small they lost all meaning.

"Pathologists are the most terrible hypochondriacs," Dr. Ratkay said ruminatively. "Everything is fatal, you see. There's no such thing as a cold you get over, a mild case of pneumonia, a benign tumour. Every time you examine a patient, the case was terminal. Pathologists live in fear." He sighed. " 'The fear which troubles the life of man from its deepest depths, suffuses all with the blackness of death, and leaves no delight clean and pure.' "

"Virgil?"

"Lucretius." Dr. Ratkay tamped tobacco into his pipe. His fingers were shaking. The skin no longer fit them quite right. It hung around his knuckles, liver-spotted, yellow with age and smoke. "I didn't want to raise my children in a pathologist's world."

"Well, you did your best," Dante observed. "With the skull on your desk and your other cheery lessons. Your World War Two was practically a catechism, Dad: And poverty begat Hitler and Hitler begat the Blitz and the Blitz begat Dresden and Dresden begat Auschwitz and on and on."

Dr. Ratkay blinked. "Was I really like that?"

"Were you like that!" Dante said, laughing and outraged at once. "It was like living with Mengele!"

Dr. Ratkay drew a match from a wooden box and struck it. His fingers were trembling. "I didn't mean it," he said softly. "I didn't mean it that way. It's just. . ." He sucked fire into the bowl of his pipe. Tiny strips of tobacco flared and fell to ash, like German villages ignited in Lancaster raids. "It is important to know those things."

"And what kind of name is Dante, anyway? Couldn't you just buy me a bus ticket to Hell on my eighteenth birthday?"

"We went to visit your Aunt Gloria, I believe," his father said dryly. "A close approximation, as I recall." Dr. Ratkay settled back in his chair, drawing on his pipe. His face seemed thin, the lines between his brows deeper than Dante remembered. Wearier.

Anton sighed. "I started medical school in the decade after the War. A tremendous amount of what we knew, especially about physiology and the treatment of trauma, came from wartime research. They used to put dogs in little wooden houses and then blow them up to study the effects. Did you know that?"