Resolute (21 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

Almost nothing in his life had ever as great an impact on Henry Kellett as Belcher's orders. At first he couldn't believe it. Then he was astonished. Finally, he became as angry as he had ever been. What was the man thinking? How could they possibly give up the search? Even more shockingâhow could they even consider abandoning four seaworthy naval vessels to certain destruction? Anybody who had even the notion of doing so, Kellett stated, “would deserve to have their jackets taken off their backs.”

He was not alone. Leopold M'Clintock had the same vehement reaction, as did all the officers of Kellett's two ships. “We still had enough provisions and spare parts for another year,” de Bray wrote in his journal. “We were all in perfect health and filled with anticipation in thinking of our planned spring voyageâ¦The order to abandon our ship was a distressing surprise to us.” Surprise indeed! Kellett and M'Clintock were not about to accept the order without a fight. If nothing else, they decided they would keep the

Resolute

and the

Intrepid

in the Arctic and continue the search without the other vessels. There was also something else that was deeply troubling. As they reread Belcher's order it became increasingly clear to them that Belcher had deliberately worded it in such a way as to make it appear that the decision to abandon the ships was as much Kellett's idea as his own. M'Clintock later wrote the details in his account of the incident:

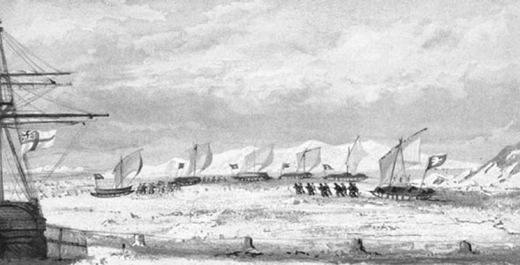

SLEDGING CREWS

from the

Resolute

leave to search for John Franklin. Both the

Resolute's

commander Henry Kellett, and Leopold M'Clintock, captain of the

Intrepid

, firmly believed that, given the courage and skill of their crews, traces of Franklin would have been found if Edward Belcher had not ordered the abandonment of their ships.

I was sent for by Captain Kellett to read over ⦠the orders from Sir E. Belcherâ¦and to give my opinion of their meaning. I did so. Some paragraphs in these long orders contradict each otherâ¦. It is implied that we are to abandon [the ships]. By his orders Sir Ed. assumes that Capt. Kellett has determined upon abandoning the ships. Now this being exactly contrary to [Kellett's] intentions ⦠[Captain Kellett] feels greatly puzzled.

Henry Kellett had twice been lied to by McClure. He wasn't about to be hoodwinked by Belcher.

Preparing a strong reply to the order, Kellett then sent M'Clintock out on the more than 250-mile journey to Wellington Channel, where he was to deliver it in person to the senior commander. In the strongest language, Belcher was told that Kellett had plenty of provisions, and two sound ships that were in no danger and in excellent position to be free of the ice when summer arrived. But Belcher would not listen. This time the order he sent back with M'Clintock was crystal clear. The ships were to be abandoned.

Kellett was devastated. But, as a true navy man, he had no choice but to obey the chain of command. Robert McClure, on the other hand, had mixed feelings. He had now been trapped in the north for four years. Writing to John Ross, he stated that the Arctic was a region “which I hope to have done with forever.” As for Belcher, he wrote: “Things are as bad as can be or as you might expect under B. Nothing but Courts Martial he, but as their Lordship will decide these matters, best to keep quiet until it becomes public which it must very speedily.”

By the end of August, the Belcher expedition was gathered at Beechey Island, preparing to board the

North Star.

Among the late arrivals was the

Resolute's

Lieutenant Mecham. On April 3, he had been sent out by Kellett to command a sledge party to Princess Royal Islands in the Price of Wales Strait in hope of finding traces of Collinson. As he had when he had found McClure's note, Mecham was now returning with exciting news. At a depot at Princess Royal Island he had found a note left by Collinson stating that, in 1851, he had taken up winter quarters in Walker Bay. Immediately heading for the bay, Mecham had reached Ramsey Island where he found another note from Collinson stating that he was going to try to sail east through Dolphin and Union Strait. Mecham could hardly contain himself. He was on the track of the lost explorer.

Suddenly, however, his sledge team caught sight of an approaching stranger. It was a lieutenant from one of Kellett's ships sent out to inform Mecham that he was to proceed immediately to Beechey Island. Puzzled by the command, Mecham and his party accompanied the lieutenant to where the

North Star

was waiting. By the time he reached the ship he had traveled a distance of 1,157 geographical miles in seventy daysâoutdoing his own former recordâand eight of those days had been spent in a tent while stormbound. It was a journey unparalleled in all of Arctic travel. Lieutenant Mecham had performed the last of the many of heroic acts accomplished by the men of the HMS

Resolute

, an achievement tempered by Mecham's discovery upon reaching the

North Star

that rather than looking for Collinson, the expedition was heading home.

ON AUGUST

26, 1854, the

North Star

, dangerously overloaded with 263 men, headed for home. Only the fact that the

Phoenix

and

Talbot

âsent to the Arctic in 1854 by the Admiralty as supply ships for Belcher's expeditionâfortunately appeared on the scene, enabling the crews to be divided between the three ships, prevented the expedition that had turned into a fiasco from becoming a probable full-blown tragedy.

Not that tragedy had been totally averted. A year earlier, as the

Phoenix

, commanded by Lieutenant Edward Inglefield (a polar explorer who disproved a troubling rumor about Franklin's disappearance; see note 2, page 270) was making one of its three attempts to reach Belcher's ships, a young officer had suddenly fallen through an opening between two broken masses of ice and died. It had been Joseph-René Bellot, Lady Franklin's “adopted” son who, after serving with William Kennedy, had volunteered to once again search for Franklin.

The

North Star

, the

Phoenix

, and the

Talbot

docked in England in September 1854. A year later Richard Collinson suddenly arrived. His had been a most unrewarding and acrimonious voyage. Tension aboard the

Enterprise

during its almost five-year wanderings had reached the point that, by the time of its unexpected but welcome return, Collinson had placed all three of his mates, as well as one of his ice masters, under arrest. When the ship docked, the vessel's surgeon and his assistant were the only officers on duty besides the commander. Already outraged at McClure for having gone off on his own, Collinson demanded that those whom he had placed under arrest be court-martialed. In turn, the officers claimed that Collinson should be brought to trial.

There were indeed courts-martial, but not for Collinson. Not only Belcher, but McClure and Kellett faced charges of abandoning their ships. It was a proceeding that all of England followed with an interest rivaling that which they had shown in the search for Franklin itself.

The observant de Bray recorded the proceedings:

Captain McClure appeared first and justified his action on the basis of written orders he had received from Captain Kellett for abandonment of his ship under exceptional circumstances. After withdrawing, the court martial declared that Captain McClure, his officers and crew deserved the highest commendations and they were all fully acquitted. Captain Kellett then appeared to give his account of the loss of

Resolute,

and produced the orders he had received from Sir Edward Belcher for the abandonment of

Resolute

and

Intrepid.

A large number of letters were read, some of them confidential; they proved that, despite the opinion of Captain Kellett and all his officers, who declared the ships would not suffer at all during the impending breakup, Captain Sir Edward Belcher, by a letter dater

25

April, had peremptorily ordered them to abandon the

Resolute

and

Intrepid

and proceed to Beechey Island. Having thus been cleared of all responsibility, Captain Kellett was honorably acquitted and in returning his sword the president expressed his complete satisfaction with the manner in which he had comported himself in the difficult circumstances in which he had found himself.

The courts-martial then turned to the actions of Sir Edward Belcher. To the dismay and even outrage of many who hung on every word of the proceedings, the court, after hearing a lengthy statement from Belcher in which he based his case on the instructions he had received from the Admiralty, decided that legally he had acted within the discretionary powers that had been given to him.

Perhaps in acquitting Belcher, the members of the court truly felt that legally there was nothing else they could do. There were many, both in the public and the press, who would always believe that it was Sir Edwards's high standing in society that had saved him from the punishment they felt he deserved. Whatever the case, the only action the court took was the symbolic yet meaningful gesture of handing Belcher back his sword in stony silence. He would never be given the command of a British naval vessel again. Soon there would be other events that would make him an even greater object of ridicule and disgrace.

CHAPTER 11.

CHAPTER 11.A Devastating Report and a Remarkable Journey

“A fate as terrible as the imagination can conceive.”

âfrom

JOHN RAE'S

report to the Admiralty, 1854

E

DWARD BELCHER'S

sudden return and the details of the inexplicable abandonment of four of his vessels threw all of Great Britain into shock. Its effect on the Admiralty was equally profound. The Lords had had enough. Too many men and too many ships had been lost in what had obviously become a fruitless endeavor. Even the

Times

, for so long a leading instigator of the Franklin rescue efforts, now changed its position. “Surely enough has been done in favour of a sentiment rather than of rational calculation,” the paper exclaimed.

Soon there was another development. Late in October 1854, John Rae suddenly arrived in England. And the Hudson's Bay Company explorer and surgeon, the man who had conducted the first search for Franklin, had startling and, in his words, “melancholy tidings,” news so important he had interrupted his latest Arctic undertaking and rushed across the Atlantic to present his report.

Rae, his report to the Admiralty stated, had launched yet another Hudson's Bay Company exploration, this one aimed at determining once and for all if Boothia Felix and King William Land were peninsulas or islands. With two boats and eleven men he had left York Factory (Hudson's Bay Company headquarters) in June 1953, and had headed for the Great Fish River that George Back had discovered and which had been renamed for him. On the way, Rae had discovered a river of his own, which he named Quoich (“cup” in Scottish) after a river in his homeland, and had spent more than ten days exploring it. After wintering in his old base camp at Repulse Bay, he and his party had set off for Boothia Felix. On April 21, while making his way there, he encountered the first group of Inuit he had seen since beginning his exploration. Immediately he noticed that a member of their party, a man named In-nook-poo-zhe-jook, was wearing a cap with a golden band, the same type of headgear often worn in the Arctic by English naval men.