Resident Readiness General Surgery (18 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

High or low temperature (>38.5°C or <35°C)

Heart rate >90

Respiratory rate >20 (or Pa

CO

2

<32 mm Hg)

Sepsis = SIRS + infection.

Septic shock = severe sepsis + hypotension.

The pillars of care involve treatment of the infection (source control and antibiotics) and resuscitation (goal-directed fluids and vasopressors).

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

Which of the following would

not

count toward a diagnosis of SIRS?

A. MAP of 55

B. Temperature of 102.3°F

C. Heart rate of 96

D. 12% bands on CBC

2.

Which of the following would be an inappropriate

first

step in the treatment of a patient in septic shock?

A. 1 L bolus of normal saline

B. IV administration of vancomycin, cefepime, and metronidazole

C. CT of abdomen to look for an abscess

D. 100% O

2

via non-rebreather mask

Answers

1.

A

. The criteria for SIRS include heart rate, temperature, respiratory rate (or Pa

CO

2

), and elevated or depressed WBC. Hypotension plus SIRS defines septic shock.

2.

C

. Although identification of infection and source control are integral parts of the treatment of the septic patient, they should not delay respiratory support, resuscitation, or administration of antibiotics. The patient should be stabilized in an intensive care unit prior to any radiological procedure.

SUGGESTED READING

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock.

Crit Care Med

. 2008;36:296–327 [published correction appears in

Crit Care Med

. 2008;36:1394–1396].

A 57-year-old Man With a Chief Complaint of Nausea and Vomiting

A 57-year-old Man With a Chief Complaint of Nausea and Vomiting

Alexander T. Hawkins, MD, MPH

You are asked to see a 57-year-old male in the emergency department with a chief complaint of nausea and vomiting. The patient reports that 1 day prior to presentation he began to experience vague abdominal cramping followed by persistent nausea and vomiting. On questioning, he reports that his last bowel movement was 3 days ago and he has not passed gas for over 24 hours. His past medical history is significant for an exploratory laparotomy and bowel resection for trauma 20 years ago. On examination, his abdomen is distended, tympanic, and diffusely tender.

1.

Name the 3 most common causes of a mechanical small bowel obstruction (SBO).

2.

How do you diagnose an SBO?

3.

What is the first decision you have to make in treating an SBO?

4.

When is nasogastric tube (NGT) placement warranted?

5.

What size NGT do you want to place and what else do you need to do to place it?

6.

List the 2 supportive interventions, besides an NGT, that are commonly ordered for a patient with an SBO.

SMALL BOWEL OBSTRUCTION

An SBO occurs when the normal flow of intestinal contents is interrupted. SBOs can be divided into 2 categories based on their etiology: functional and mechanical.

Functional

A functional SBO refers to obstipation (failure to pass stools or gas) and intolerance of oral intake resulting from a nonmechanical disruption of the normal propulsion of the GI tract. This is synonymous with an ileus. As a surgical intern, you will mostly come across these patients in the immediate postoperative period. Most ileuses will resolve on their own with conservative measures such as IV fluid resuscitation, nasogastric decompression, minimization of narcotics, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, and ambulation. Gum chewing has been shown to stimulate gut motility and is a nice option as one of the few active measures you can employ.

Mechanical

A mechanical SBO refers to intrinsic or extrinsic physical blockage of the GI tract. As a functional SBO rarely requires surgical intervention (and some surgeons say is not even an SBO at all!), we will focus more on the mechanical SBO. Going

forward, when we are talking about an SBO, we will be discussing a

mechanical

obstruction.

Answers

1.

The most common cause of an SBO is postoperative adhesion (56% of cases). About 1 out of every 5 patients undergoing an abdominal operation will develop an SBO in 4 years. The type of abdominal surgery impacts the risks of SBP. Laparoscopic operations result in much lower rates of SBO than open operations.

Malignant tumors or strictures of the small bowel can cause intrinsic blockage and are the second most common cause of SBO (30% of cases). Strictures can result from Crohn disease, ischemia, radiation therapy, or drugs (NSAIDs, enteric-coated KCl).

Hernias cause extrinsic compression and are the third most common cause (10% of all cases). Make sure you check for hernias in any patient you suspect of an SBO. Ventral and inguinal hernias account for most of the cases, but internal hernias also can cause an SBO.

Other less common causes of SBO in the adult population are intussusception, volvulus, and gallstone ileus.

2.

First, you have to suspect it. Patients presenting with SBO will report nausea, vomiting, and obstipation (failure to pass stools or gas). Often they will report a history of previous abdominal operations. Their abdomens will be distended and tympanic. Abdominal pain is usually dull and diffuse. Focal or generalized peritonitis is a danger sign of ischemia and/or perforation.

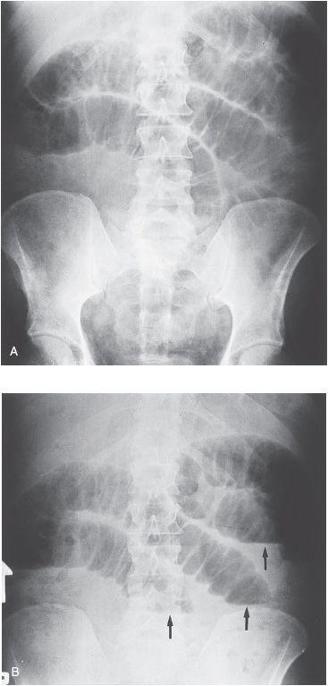

Radiological examination should include an upright chest x-ray to rule out free air as well as supine and upright abdominal films (aka KUB) to look for air–fluid levels and dilated loops of bowel (see

Figure 14-1

A and B).