Resident Readiness General Surgery (7 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

Figure 5-3.

Sample template: procedure note. Highlighted areas indicate tips and fields to be filled in by the writer.

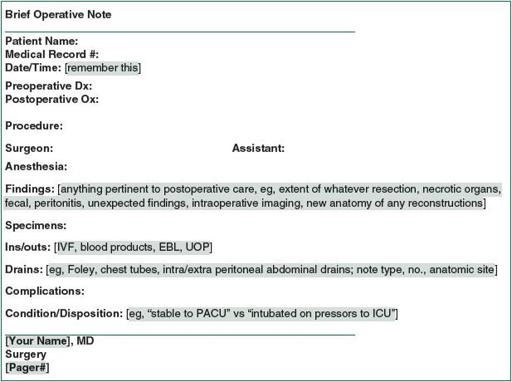

Figure 5-4.

Sample template: brief operative note. Highlighted areas indicate tips and fields to be filled in by the writer.

2.

Preencounter:

A. Prioritize:

i. As soon as possible after hearing about a patient, eyeball the patient to determine if she or he is sick or not sick and how much time you have to review the medical records/take care of more urgent issues before seeing him/her.

B. Note preparation:

i. If the patient is not sick and you have the luxury of time, use your general H+P template to start a preliminary note on the patient, copying and pasting in any pertinent information from the medical records (name, age/sex, medical record no., PMH, medications, allergies, recent labs, and imaging).

ii. Print and bring with you

to confirm

any information in your note and fill in the blanks.

Note

: Do not post information in your note that you, yourself, have not yet confirmed with your patient—this is unethical and dangerous.

If you must include an unconfirmed piece of data (ie, a medication list obtained from the electronic medical record of an obtunded patient), then you should clearly note the source and the fact that the data have not been confirmed.

3.

During the encounter:

A. Once-over:

i. The moment you walk into the room, make note of general patient observations and vital signs. Address any abnormalities immediately—for example, hypotension, hypoxia, and somnolence—and if severe, alert your senior. If no acute issues jump out at you, jot down vitals and move on. Include vital signs in every note—they are essential objective data.

B. The CC:

i. Before mashing on a belly, make absolutely certain you understand what is ailing your patient, that is, the

primary

issue that drove him/her to the hospital, and the primary focus of everything you do henceforth.

C. Everything else:

i. Fill in the blanks. Follow your system to avoid missing any key history or exam findings. Formulate a quick impression in your head. Offer to the patient/family/primary team to return and explain impressions/plans once you discuss with your higher-ups.

4.

Post encounter:

A. Fill in gaps:

i. At a computer, pull up your skeleton note, fill in information acquired from the patient, and fill in any gaps by quickly perusing online medical records, calling care providers or pharmacies, and reviewing lab/culture/imaging data.

B. Process the information:

i. Jot down your impressions. (Sick or not sick? DDx? One or multiple active issues?)

ii. Jot down any key diagnostic or management moves you would make.

iii. Jot down any questions for your senior/fellow/attending, lest you forget to ask (eg, are we going to the OR/should I hold tonight’s Coumadin dose?).

iv. A wise adage: There are interns who write things down, and there are interns who forget.

C. Discuss:

i. After taking a

minute

to collect your thoughts, page your senior and present the case in a concise, organized manner. Follow your H+P or abridged SOAP format, depending on the context. Remember to stick to your system, the same way every time. The alternative—presenting data out of order and forgetting key details—generates verbal diarrhea, which confuses your listener, guarantees you getting interrupted and flustered, and hinders patient care.

ii. Write down the plan dictated by your senior, and remember to amend both your note and your to-do list with any additional impressions and plans dictated by your attending.

D. Execute:

i. Carry out the plan.

ii. By now, your note should already be written. Print, sign, and place in the chart as promptly as possible, that is, in real time for daily progress notes and postoperative checks, and within several hours to half a day for admissions/consults.

Note

: Patient care always comes first. In the worse case scenario, when you are between bedsides of unstable patients and unable to write a complete admission or consult note, jot a “brief note” in the chart (date/time, 1-liner about the patient, and brief plan) and remember to write the full note as soon as time allows.

ADMISSION NOTE SPECIFICS

Purpose: To organize myriad data into a comprehensive

and

concise H+P that highlights your patient’s primary problem and provides all necessary baseline data and proposed plans. This note should help focus and guide your team and consultants.

Essentials:

1.

As mentioned before, make sure you understand your patient’s chief complaint.

2.

Confirm and document all medications, doses, and allergies. While tedious, this is helpful for consultants and essential to writing appropriate admission orders.

3.

Tailor the exam to the chief complaint, but remember to check and document baseline vitals, mental status, cardiopulmonary exam, and pulses, as

any of these things can deteriorate perioperatively or over the course of an acute illness and are difficult to monitor if you have no knowledge of the patient’s baseline.

4.

Guided by insight from your senior/fellow/attending, write a clear assessment of the patient’s condition and cause of chief complaint, and lay out a comprehensive plan by organ system or issue (see

Figure 5-1

).

Note

: Do not document anything that you are unsure about and have not clarified with your senior. Assumptions lead to confusion and, in the worse case, patient harm.

CONSULT NOTE SPECIFICS

Purpose: To identify and address the specific reason for consultation with pertinent data, impressions, and management recommendations. Stay focused.

Essentials:

1.

Absolutely speak with the primary team to clarify their exact question/reason for consultation. If the intern is unclear, go up the chain. If you are unclear, you waste a lot of people’s time. Document the reason for consultation (in addition to or in lieu of CC) in your note.

2.

Document the date/time of consult.

3.

Clarify and document from whom and to whom (ie, from/to which service and attending) the consult is being requested.

4.

Focus your history and exam on the reason for consultation. You are not the patient’s primary doctor.

Caveat

: If you encounter an unstable patient, be a doctor, alert the primary team immediately, and help stabilize the patient as appropriate.

5.

Communicate a very

specific

assessment and plan to the primary team, in person and in writing. Include:

A. Your team’s impression of the problem/question being asked

B. Specific management recommendations, including what exam findings/vital signs/labs/imaging to monitor and how often, diet/NPO status, IV fluids, medications, surgery, and other procedures

C. Threshold to call, and whom to call, with any questions or concerns

6.

Remember to document with whom you discussed the plan on both your and the primary team’s note.

DAILY PROGRESS NOTE SPECIFICS

Purpose: To provide a concise and thoughtful daily update of inpatient progress and anticipated disposition.

Remember

: These notes are a major avenue of communication with attendings and consults and are useless if late, illegible, inaccurate, or lacking in explanations for any new plans.

Essentials:

1.

Pare down the H+P to a SOAP approach/note in real time (see

Figure 5-2

).

2.

Develop and stick to a system that enables you to write your notes/drop in the charts on rounds. Get help when possible (thank you, medical students).

3.

Learn to differentiate sick from not sick, and pathway versus nonpathway progress (eg, mild postoperative nausea on POD #0 vs nausea/vomiting on POD #3 s/p laparoscopic colectomy).

4.

Learn and only include essential data (markers of progress, eg, flatus vs nonpathway complaints/exam findings).

5.

Remember to include at least a quick impression and plan to explain to later-morning rounders (attendings and consultants) why you are enacting the plans listed in your note.

POSTOPERATIVE CHECK SPECIFICS

Purpose: To identify and document any acute, postoperative, life-threatening complications, any active issues requiring timely management, and baseline patient condition—this is particularly important when new issues arise over the ensuing 12 to 24 hours.

Essentials:

1.

As for daily progress notes, pare down the H+P to a SOAP approach/note in real time (write/drop your note in the chart while assessing your patient), learn how to determine sick versus not sick, and learn/document only essential data.

2.

Pay particular attention to harbingers of sickness (eg, pulmonary issues, unexpected hemodynamic instability, chest pain, focal neurologic deficits) and address as appropriate.

3.

Check for, document, and manage common postoperative issues (eg, pain, nausea, oliguria, wound/drain issues).

4.

Remember to follow up on all pending postoperative labs, imaging, and bedside reassessments if necessary. Document any abnormal findings or changes in the original plan.

ACUTE EVENT SPECIFICS

Purpose: To document all/only essential information in a timely manner without compromising patient care.

Essentials:

1.

Obvious events that require documentation include death, cardiopulmo-nary arrest, unresponsiveness, and hemodynamic or neurologic instability

requiring transfer to the ICU. Less obvious events that still require documentation include any new symptom or change in exam that prompts unplanned labs/imaging/studies/procedures/transfers.

2.

Stick to your SOAP system for structure amidst chaos. While approaching the patient’s bedside, run through

Figure 5-2

, tailored to this setting:

A. Note the date and time.

B. S: What did the patient or provider complain of?

C. O: What are the current vitals and trend since the patient was last well? What is the patient’s current exam and trend since last well? (It can be helpful for you or another person to grab the chart to check recent notes/labs/imaging.)

D. A/P: What postoperative/hospital day s/p what procedure/illness is this patient? What is my quick impression and plan? (It can be as simple as sick; stabilize airway, breathing, circulation [ABCs]; call senior.)

E. Use this system to organize your thoughts, actions, communications with seniors, and, lastly, your event note.

3.

Remember priorities. First, take care of your patient. Then, jot your note in the chart, formatted as above. Timing is situation dependent. You will ideally complete this task within several hours of the event, when either your patient is improving or another doctor has relieved you, at least temporarily.