Reporting Under Fire (21 page)

Read Reporting Under Fire Online

Authors: Kerrie Logan Hollihan

After she recovered, Gee Gee followed the same path that other Medill graduates took and went to work for a small newspaper. In 1960, she landed her dream job at the

Chicago Daily News.

Every day she watched the reporters who milled around the city desk, hard-driving, crusty menâand the two lone women permitted to work with them. They were newspapermen (even the women), a solid team hard at work competing with the other three dailies in the big newspaper town of Chicago.

The

Daily News

was also a paper quite unlike papers today; it was journalism quite unlike journalism today. We quite simply “reported” what was going on. We did not write columns or our own personal interpretations on the news pages. We reported fires and murders and

investigations and the statements of institutions. It was a much straighter and much more honest job then, and it was also a hell of a lot of fun.

Gee Gee Geyer got her first big story at the

Daily News

by dressing up as a cocktail waitress and listening in on conversations as she served champagne at a Mafia wedding in Chicago. The next Monday, her story and photo appeared on the front page with the lead “The mob went to a party and I went along for the ride.” But for the most part, her days were filled with less risky stuff, the nuts and bolts of reporting crime, fires, city politics, and school news.

She got to know neighborhood organizers, including a reputed radical named Saul Alinsky, who, the conservative Gee Gee felt, was unfairly labeled a dangerous man. She admired Alinsky's dedication to improving life for Chicago's underprivileged people, and his honesty too. (Alinsky had famously refused a bribe from “Hizzoner” Mayor Daley.) She studied his tactics and learned from them. When City Hall threatened to tear down Jane Addams' aging settlement building, Hull-House, a Chicago and American landmark, Gee Gee organized a group to save it and won.

Still, Georgie Anne Geyer longed for an overseas assignment.

Daily News

foreign correspondents were all men in their 50s and 60s, so there seemed to be no chance of her getting out of Chicago. Then in 1964, she got her break when she won a grant to study in Latin America and her editor agreed to let her report from there for the paper. After all, she was traveling on someone else's tab.

Gee Gee flew to Peru and set out to write a feature on a sister city project between Pensacola, Florida, and Chimbote, a seaside city. Kids in Pensacola were raising money for Chimbote to

build a sports stadium, a gift for Chimbote's impoverished children. On the surface, everything looked good, until some local newspapermen hinted at dirty dealings. In the classic tradition of reporters, Gee Gee asked around and discovered the donor of land for the new project was the biggest crook in town. He owned a brothel across the street.

Gee Gee requested an interview, and he agreed but was careful not to show his hand as they talked. It took a long hot afternoon and many glasses of red wine before Gee Gee, feeling desperate for information, decided to appeal to the man's vanity. “I see that you are an intelligent man ⦠a man as smart as you would not give up something without getting some for himself.” Indeed not. The egotistical crook brought out blueprints. One glance, and Gee Gee made out a ring of small rooms inside the stadium. They were meant for a new brothel.

“The bishop of Chimbote waxed ashen when he got the storyâthen he was enraged,” Gee Gee recalled. Pensacola quietly dropped its sister city project.

Gee Gee made her first trip to a war zone when civil war erupted in the Dominican Republic. Early on, her editor argued that a street war was no place for a woman and offered to send her to Vietnam, where she'd be safe in a Saigon hotel. This was a ludicrous suggestion, and when she gave him an I-cannot-believe-you-just-said-that look, he agreed to let her go to Santo Domingo. But her editor's worries stuck with her, and Gee Gee felt sick with panic as she packed for the trip, convinced she'd get shot the moment she arrived.

When the plane's door opened and Gee Gee looked out at dozens of Marines at the Santo Domingo airport, some of them shirtless in the Caribbean heat, she relaxedâand realized that she was learning a life lesson. “In that languid scene,” she wrote when she looked back later, “I lost forever that kind of

inordinate, unspecified, undifferentiated fear. There were times when I was afraid later, but never like that.”

Gee Gee happily found herself living the reporter's dream. In the Hotel Embajador were newsmen, diplomats, generals, exiled leaders from neighboring Haiti, writers, and curiosity seekers. There was a 7

PM

curfew, so in the hotel bar “every night we argued, drank, brawled, and fought the Battle of Santo Domingo.” Emotions ran hot in bitter arguments between the “democrats,” Juan Bosch supporters, and conservatives who backed old members of the Rafael Trujillo dictatorship because they opposed communism. Gee Gee believed that Bosch was a constitutionally elected president and that President Lyndon Johnson had made a mistake sending in the Marines to back the other side. It was not the first time she would discover that the US government didn't have a clear understanding of Latin American politics.

Reporters had access to the warring parties, and Gee Gee adored that. “Weâand only weâcould go to all sides. Only we could know everything. Only we could put

all

the pieces of a complicated puzzle together.” As she carried out her interviews, she began to realize something more: she must report not just whats but whys. The Dominican Republic had its own history and culture that she must understand and interpret for her American readers.

She asked around about the talented but troubled young rebels, “fanatics” she thought, who were fighting for the revolution. Why would they fight to the death? A local professor gave her the answer. “What you have here is the problem of desperation,” he explained. “They have a suicidal feeling that is aroused by conflict with a great power. You have a small person, who's proud, and he feels that he has nothing to lose but his life, so âGo ahead and kill me.'”

It was a pathologyâa pattern, Gee Gee discoveredâthat she witnessed among rebels and terrorists time and again over the next 50 years. Desperate young men were willingâeven hopedâto die fighting Americans and others in places such as the Dominican Republic, Vietnam, Guatemala, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Iraq, and Afghanistan. It was a pattern that continued to puzzle Americans and the US government.

In the spring of 1966 Gee Gee turned her eyes to Cuba, hoping to get an interview with Fidel Castro. No one had seen the young dictator for months, and rumors flew that Castro was sick or dead. Several times Gee Gee missed her chance to leave from Santo Domingo for Cuba, and there weren't any flights from the United States. Still in Santo Domingo, she was sure Castro's people had her request, but she was a long time waiting for a reply. She ended up going home to Chicago to visit her sick father, and then the call came. With no direct flights from the US to Communist Cuba, Gee Gee arrived in Havana via Mexico City. There, without warning, she was whisked away to see the ghostly Castro.

Gee Gee was empty handed, without pen or notebooks. Castro began a long-winded meeting, and all Gee Gee could rely on were her ears and her memory.

I could take no chance on losing this apparition, so I began to work out a certain method I later perfected. I learned to focusâvirtually to set my mind onâcertain important phrases as he uttered them. I had the conscious feeling of a hand coming out of my mind and grasping them and freezing them for a moment. I found that with this method I could keep quotes perfectly for at least three days.

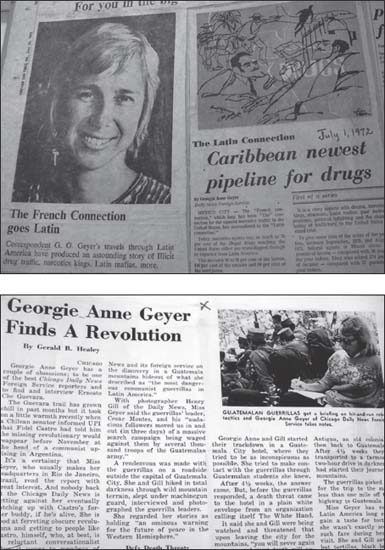

Before the days of digital images, Georgie Anne Geyer stashed snapshots of her newspaper clips in scrapbooks.

Courtesy of Georgie Anne Geyer

Gee Gee found Castro captivatingâboth sweet and ruth-lessâan ego-bound man who was motivated not by money or women but pure power. Castro

was

the revolution, the idol of agitated young rebels around the globe. He talked endlessly, carrying on a seven-hour interview with Gee Gee that was interrupted only when Castro decided to go out for ice cream. He made a point of boasting that Cubans had 28 flavors, more than the Howard Johnson's chain in the United States. (After Gee Gee's interview with Castro ran in American papers, Howard Johnson's stated it now had 32.) The

Chicago Daily News

proudly ran a photo of Gee Gee and Castro under the astonishing headline: O

UR

M

AN IN

H

AVANA

I

S A

G

IRL.

Again Gee Gee felt frustrated that she couldn't fully understand Cuba and its revolution. How, she asked, could Cubans flip from their lives as Westerners in a Christian nation to Communism and its official atheism? But over the next two months in Cuba, when she was Castro's guest many times, she realized that a cult of personality surrounded Castro. For many, the Cuban dictator fit the Latin American notion of a

caudillo

âa charismatic strongman. Castro exerted “mind control,” she wrote.

In 1968 the

Daily News

sent Gee Gee to another revolution, this time in the jungle mountains of Guatemala. She wanted to interview rebel guerillas, well-educated young Marxists who hid from the authorities as they tried to bring about a people's revolution among Guatemala's wretchedly poor peasants. Gee Gee knew there was no point in asking for a meeting directly, because no one would acknowledge it. One simply didn't talk about these things openly. “You're not playing games; you're playing with temperaments turned to calculated and sometimes spontaneous brutality, all revolutionary collegiality one

moment and calculated savagery the next.” Again she played the waiting game by “looking around” Guatemala City, hoping to make things happen.

Her patience paid off. On a tip, she paid a social call to a lawyer who belonged to the Communist Party, and before she left, hinted that she'd like to meet the guerillas. “But you know I have nothing whatsoever to do with them,” he replied smoothly. “Oh, I know, I know that,” Gee Gee assured him. But the polite stranger was well connected, and Gee Gee got her meeting with the guerrillas after a “dramatic ballet” of a car ride to their hideout. She wrote up the story, tucked it in her purse, went to a cocktail party where she said nothing about the interview, and left Guatemala that night. The

Chicago Daily News

ran her story the next week and syndicated it across the United States.

But she had made enemies. When Gee Gee returned to Guatemala that fall, she was followed. A desk clerk gave her a letter, and she opened it to see a hand outlined on it, the distinctive symbol of Mano Blanca, the White Hand, a right-wing terrorist gang funded by Guatemala's big landowners. The White Hand maimed, mutilated, and killed, not just Marxist rebels but ordinary Guatemalans who wanted to establish a democracy.

We know you are a spy, the letter read, calling Gee Gee a

“puta,”

a whore, as well. Gee Gee, who had resented her blond, “Illinois corn-fed” looks, was amused at the irony of it all.

She made contact with the rebels. This time, Gee Geeâclad in sports clothes and ordinary flatsâand her photographer, Henry Gillânot in the best shapeâtrekked far into the mountains to get their interview. They hiked overnight until near daybreak, sleeping on the ground and digging in their feet to keep from rolling off the mountain. Gee Gee spent three days with the rebels and the mix of peasants who fought with them, speaking Spanish and listening to their stories. An old peasant

talked of being forced from his village, a story she heard over and over during her years in Central America. A young guerilla startled her by speaking openly and saying that Fidel Castroâ the idol of revolutionariesâwas a “big egocentric.” “But we won't be like that,” the rebel promised. Later, Gee Gee would think about his naive promise. “In years to come I would hear that phraseââWe won't be like that; we will be different'âso many, many sad times.”

The trek out proved to be dangerous. When the army brushed by, Gee Gee's small party fell flat on the ground. Their guide got them lost, and by the end one big guerilla was pulling Gee Gee up over the rocks as another dragged Henry Gill. In the end, it was worth the effortâthe

Daily News

ran a series of articles about the Guatemalan guerillas, and they appeared in newspapers around the world.

Now a “marked woman” in the eyes of the Guatemalan government, Gee Gee took great care whenever she returned. She saw no sign that the White Hand was trailing her, and she began to think she was forgotten. Then in 1972, she returned again. After dinner with a friend, she said good-bye and went to the elevator where she spotted a stranger, “tall, strung-out,” who had been in the lobby that afternoon. He missed the elevator, and Gee Gee fled to her room and bolted the door. The elevator doors opened again, and she heard him coming. Her lock turned, but the bolt held fast. She called and a bellman came to the rescue, but by then, her attacker was in the bar and denied everything. Gee Gee knew in her gut that the White Hand had tried to carry out its threat from that long-ago letter.