Reporting Under Fire (18 page)

Read Reporting Under Fire Online

Authors: Kerrie Logan Hollihan

At the control ship we circled again, waiting for H hour.

Aircraft carriers and navy cruisers bombarded the beach in a final pounding. There was silence, until an air assault swept over the landing craft. Silence again followed, and then another assault. Then more silence.

The control ship signaled that it was our turn. “Here we go keep your heads down!” shouted Lieutenant [R. J.] Shening. As we rushed toward the sea wall an amber-colored star shell burst above the beach. It meant that our first objective, the cemetery, had been taken. But before we could even begin to relax, brightly colored tracer bullets cut across our bow and across the open top of our boat. I heard the authoritative rattle of machine guns. Somehow the enemy had survived the terrible pounding they'd been getting. No matter what had happened to the first four waves, the Reds had sighted us and their aim was excellent. We all hunched deep into the boat.

“Look at their faces now,” John Davies whispered to me. The faces of the men in our boat, including the gin-rummy players, were contorted with fear.

Their boat smashed into the sea wall as bullets whined overhead. The marines still crouched in the boat.

“Come on, you big, brave marines let's get the hell out of here,” yelled Lieutenant Shening, emphasizing his words with good, hard shoves.

The first marines were now clambering out of the bow of the boat. The photographer announced that he had had enough and was going straight back to the transport with the boat. For a second I was tempted to go with him. Then a new burst of fire made me decide to get out

of the boat fast. I maneuvered my typewriter into a position where I could reach it once I had dropped over the side. I got a footing on the steel ledge on the side of the boat and pushed myself over. I landed in about three feet of water in the dip of the sea wall.

A warning burst, probably a grenade, forced us all down, and we snaked along on our stomachs over the boulders to a sort of curve below the top of the dip. It gave us a cover of sorts from the tracer bullets, and we three newsmen and most of the marines flattened out and waited thereâ¦.

One marine ventured over the ridge, but he jumped back so hurriedly that he stamped one foot hard onto my bottom. This fortunately has considerable padding, but it did hurt, and I'm afraid I said somewhat snappishly, “Hey, it isn't as frantic as all that.” He removed his foot hastily and apologized in a tone that indicated his amazement that he had been walking on a womanâ¦.

Suddenly there was a great surge of water. A huge LST was bearing down on us, its plank door halfway down. A few more feet and we would be smashed. Everyone started shouting and, tracer bullets or not we got out of there.”

Maggie's typewriter survived the assault, but she never explained how she kept her paper dry.

Maggie made it to the navy's flagship USS

Mount McKinley,

the only place any reporter could file a story about the invasion of Inchon. Then she was discovered and forbidden to return to the

McKinley

between 9

PM

and 9

AM

, a distinct disadvantage because

New York Times

reporters could file a story when she

couldn't. She slept on shore, greatly annoyed that the male reporters who bunked on the

McKinley

had real eggs, not the disgusting powdered kind, for breakfast.

After the Korean War, Marguerite Higgins married General Bill Hall in 1952. They had three children. Their first arrived premature and lived only five days. Maggie's heart was broken. She had seen death so many times, and she had thought about soldiers' families who would grieve when an army chaplain knocked on their doors. Following her daughter's death, she was grateful for “the warmth and new life infused in me by the compassion of others,” she wrote in

News is a Singular Thing,

her memoir published in 1955. It was the first time that Maggie admitted that she understood what real compassion was.

Just in her mid-30s when she sat down to reflect on the 11 years she'd worked as a war correspondent, Maggie's words spoke with a growing maturity and self-awareness about the story of her own life.

For the simplest factsâthe difficulty of love, the futility of resentment, man's degradation under tyrannyâdo not really come through to me until I find them out myself from personal experience ⦠until I made these journeys they meant nothing, for I did not understand how they applied to me and to my times.

It was unusual in the 1950s for a married woman with children to work outside her home. Maggie Higgins didâand she kept her own name on her byline. She traveled back and forth to war zones through the rest of that decade and went to Vietnam 10 times, starting in 1963. That year she won prestige by becoming a columnist for

Newsday.

Sometime during her travels to Southeast Asia, she was bitten by a sand flea that infected her with a fatal illness. Doctors couldn't determine what she had for weeks until they diagnosed leishmaniasis, a flesh-eating tropical disease, but they had no effective way to treat her. (Leishmaniasis is treated today with a round of antibiotics costing less than $10.) As she grew more ill, she was moved to Walter Reed Army Hospital, where Maggie continued to work in her hospital bed.

On January 3, 1966, she died at Walter Reed; she was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Marguerite Higgins Hall was 45 and left two young children and her husband.

In the later part of the 1900s, Marguerite Higgins became the subject of both popular biographies and scholarly research in women's history that raised questions. Was Marguerite Higgins the cold, scheming, take-no-prisoners woman portrayed by some of her biographers? Or was Higgins condemned because she was a woman who behaved like a man in going after what she wanted?

In his memoir,

Tokyo and Points East,

Keyes Beech devoted a chapter to Maggie Higgins. Beech, who liked and respected women, drew an evenhanded assessment of his coworker. Yet in the same passage, Beech's words reflected a view of women common to men of his generation:

Despite her success, Higgins never gave her readers what they really wanted. What they wanted was the “woman's angle” on war. To her credit, Higgins never stooped to that. Any one of her dispatches might have been written by a man.

In her quest for fame, Higgins was appallingly single-minded. Almost frightening in her determination to overcome all obstacles. But so far as her trade was concerned, she had more guts, more staying power, and

more resourcefulness than 90 percent of her detractors. She was a good newspaperman.

It was a tragedy for the world to lose Marguerite Higgins at such a young age. No doubt there was much more for her to say.

Ancient Peoples, Modern Wars 1955â1985

I

n 1956, a junior senator from Massachusetts, John F. Kennedy, declared that “South Vietnam represents the cornerstone of the Free World in Southeast Asia.” South Vietnam's strategic location along the east coast of Indochina made it the perfect spot for the US military to take a stand for democracy against North Vietnam, whose Communist government and Viet Minh soldiers had struggled for independence as far back as World War II. The weak, corrupt South Vietnamese government had its own internal enemies: the Vietcong, Communist guerillas who were backed by North Vietnam.

Senator Kennedy became President Kennedy in 1961, and his administration stood determined to combat Communism in small but strategic countries such as Cuba, just 90 miles from the Florida coast, and Vietnam, thousands of miles away but equally

vital in the Cold War confrontation against the Soviet Union and Communist China. The Kennedy administration sent military advisors to South Vietnam in 1961, and President Lyndon Johnson, who succeeded Kennedy after his assassination in 1963, approved a massive transfer of US military equipment and combat soldiers to safeguard South Vietnam, beginning in 1965.

From the air, American B-52 strategic bombers attacked North Vietnam and dropped bombs along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, its supply line to the south. On the ground, US infantrymen fought a guerilla war in Vietnam's jungles and highlands. By 1968 there were more than 500,000 American troops in Vietnam.

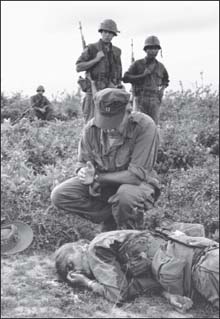

Combat photojournalist Dickey Chapelle (born Georgette Meyer in 1919) covered World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. On November 4, 1965, as she patrolled with US Marines near a South Vietnamese river, the Marine just ahead tripped a Vietcong land mine. He survived, but shrapnel tore open her throat. Dickey Chapelle died minutes later. AP photographer Henri Huet recorded these last moments as an Army chaplain gave her the last rites of the Roman Catholic Church.

©Associated Press

The war was a disaster for all involved. One million Vietnamese people, civilians and military, died from 1965 to 1975, and the United States lost 58,220 soldiers, sailors, airmen, and nurses. The United States became a nation divided by the conflict. Bitter arguments about the country's role in Vietnam divided Americans into “hawks,” supporters for the war effort, and “doves,” those who said it was time for the US military to pull out.

The folks at home watched news film shot just the day before on the nation's three television networks: ABC, CBS, and NBC. Black-and-white footage from Vietnam, with reporters on camera to explain the scene, showed disturbing pictures of wounded soldiers and Vietnamese children. Such reporting, plus strong feature reporting in newspapers, brought the war home to Americans as never before.

For the first time, women correspondents were acceptedâif not always welcomedâin Vietnam. Martha Gellhorn flew in, as did Marguerite Higgins. There were many others: Liz Trotta of NBC, Denby Fawcett, Ann Bryan Mariano, Beverly Deepe, Kate Webb, Anne Morrissy Merick, Ethel Payne, Jurate Kazickas, Edie Lederer, Tad Bartimus, Tracy Wood, Laura Palmer, and Gloria Emerson.

REPORTING FROM PARIS AND SAIGON

Now Vietnam is our word, meaning an American failure, a shorthand for a disaster, a tragedy of good intentions, a well-meaning misuse of American power, a noble cause ruined by a loss of will and no home front, a war of crime, a loathsome jungle where our army of children fought an army of fanatics.

â Gloria Emerson

It's not typical that someone writes her own obituary. Gloria Emerson did, and friends found it in her apartment after she took her own life on August 4, 2004.

Gloria Emerson, an award-winning journalist and author who wrote about the war in Vietnam and the Palestinians in Gaza, died at her home in Manhattan at the age of 74. She had been suffering from Parkinson's disease, said her physician Karen Brudney.

Sick with Parkinson's disease, she had lived in pain and despair for the past year. Her doctorâalso her friendâknew of her plans and begged her not to follow through. Yet Gloria Emerson, who had watched and written about the pain of others for decades, chose to put an end to hers.

Gloria Emerson was a war reporter for the

New York Times

and covered the Vietnam War in the early 1970s. Her mission was to tell what she saw as truth about the war, the US military presence there, and its impact on ordinary people, both Vietnamese and American. She didn't write the hard news of troop movements, military offensives, bombing runs, or the troubled politics of South Vietnam's shaky, crooked government. Instead, her crisply written profiles drew readers into the experience of vast numbers of Vietnamese caught up in their devastating civil war.

Gloria had listened to people's stories for years. Born in New York City in 1929, she grew up in Manhattan, the daughter of a chorus girl named Ruth Shaw who married an heir, William Emerson, grandson of an oilman who claimed to come from of the same family as the writer-philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson. Both of Gloria's parents were alcoholics, and her ne'er-do-well father couldn't afford a pricey private school for Gloria, so

she attended an all-girl public high school in Manhattan. Gloria wrote poetry for its literary journal, the

Sketchbook.

In a poem, “Rebellion,” she voiced a wish to climb to where gulls fly, “And scoop a cloud up in my pocket/And beat my fists against the sky.” Gloria wasn't like the other girls. She was sharp-edged and took a no-nonsense approach to life.

When she was a little older, people thought she was an alumna of Vassar College, one of the Seven Sisters colleges. (In Gloria's day, young women were refused entry into all-male Ivy League schools.) The truth was, her father hadn't been able to afford any kind of college for Gloria after she graduated high school in 1946, so she went to work. She got a job with the

New York Journal American,

though she was restricted to writing only for its fashion pages and not under her own name. But for herself, she created an image of polished sophistication. Six feet tall and slender, she was hard to miss at a party. In her 20s, she cut her heavy dark hair in a swingy pageboy and painted her nails dark red, trademark styles she never gave up.