Remembering Conshohocken and West Conshohocken (3 page)

Read Remembering Conshohocken and West Conshohocken Online

Authors: Jack Coll

Josiah White and Erskine Hazard owned and operated a rolling mill that produced nails and wire at the falls of the Schuylkill (East Falls). The partners depended on coal shipments from the coal region located in upstate Pennsylvania and needed a cost-effective method of shipping the product. In 1815, White and Hazard organized the Schuylkill Navigation Company and petitioned the State of Pennsylvania for the right to make the river navigable.

Work began on the Schuylkill Canal system in 1816 with the building of a dam at the falls of the Schuylkill, followed by Flat Rock Dam. In just twelve years, the company constructed 108 miles of the canal system, starting at the Fairmount Dam in Philadelphia to just below Pottstown. With 46 miles of slack water, or pools created by dams, the 62 miles of actual canals included 120 locks, including one in the Connaughtown section of Conshohocken.

The canal was completed in Conshohocken in 1824 and was a shot in the arm to local industry. Mules would pull the boats loaded with cargo along the canal in and out of the city of Philadelphia. In 1831, John Wood and his son Alan walked along the towpath of this canal looking for a location for their iron mill. Once inside the Conshohocken village boundaries, the father and son team decided that the canal could not only provide the rolling mill with transportation but also with power, with a water wheel.

The Woods entered into an agreement with the Schuylkill Navigation Company for the use of the land and water, signing a yearly lease of twenty-five cents per running foot of land and an annual rent of $1,000, giving them the right to use the canal's water. Following the completion of the canal, the company sold a majority of the land to James Wells, who later opened the Ford Hotel and Railroad Depot. Cadwallader Foulke also purchased a large tract of land from the canal company and established a large farm in lower Conshohocken. Foulk agreed to a deal with the canal company to use water from the canal for his crops. Other property on the west side was later sold to members of the Wood, Tracey, O'Brien, Hallowell, Trewendt and Jones families as well.

In 1949, the Schuylkill Navigation Company declared bankruptcy and deeded all its properties to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The canal was in operation as late as 1925, but only a handful of boats remained in operation. Today, what remains of the canal system is mainly used for recreational purposes. A great view of the canal still exists in the Manayunk section of Philadelphia just behind Main Street.

HE

B

IRTH OF

I

NDUSTRY IN THE

V

ILLAGE

The only businesses that thrived in the small Conshohocken village were basically those that catered to the travelers who used the river to move goods and weary horse and carriage travelers. By the 1830s, the David Harry Gristmill had long been established, as was Simons Clothing Store. Richard Thomas owned and operated an old mill, and the Seven Stars Hotel just outside of town had been established since the early 1700s.

But the majority of the businesses were blacksmith shops, including John Wagner's blacksmith shop on the west side of the river, with two black- and whitesmith shops in the village (a whitesmith shop makes silver kitchen utensils).

The businesses that really thrived were the taverns and inns along the Schuylkill, like the Spring Mill Inn and Ferry owned and operated for a time by Reese Harry. Peter Legaux had established Spring Mill Inn and Ferry years earlier under an act of assembly in 1789. Flatboats were used to carry loads of ox teams across the river in a safe manner. The main rope stretched across the river, with guide ropes on both sides of the cable. The occupants of the boats could propel themselves back and forth across the river.

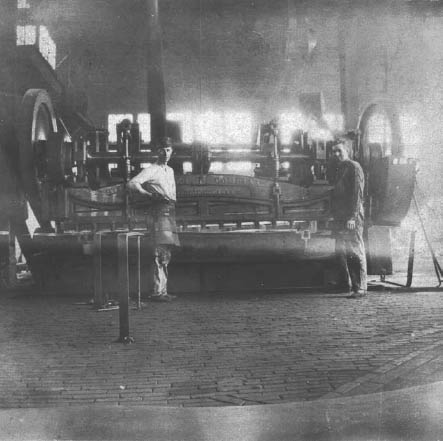

Conshohocken industry was the family foundation for more than a century in the borough, with Alan Wood Steel leading the dozens of steel and other mills that called Conshohocken home. This photograph shows Frank Staley on the left with his co-worker at the Schuylkill Ironworks in 1907.

While a few small businesses flourished in the Conshohocken village, it was the canal that led to the formation of J. Wood & Son Iron Company. On September 3, 1831, James Wood and his son Alan entered into agreement with the Schuylkill Navigation Company. The Woods would rent, and later purchase, the ground along the canal. The land was described as being on Matson's Ford road between the canal and Schuylkill River fronting Mill Street. The Wood family and the Wood business would play a large part in the incorporation of the borough. The Wood family would enjoy more than a century of success in Conshohocken.

T

'

S

A

BOUT

T

IME TO

I

NCORPORATE

By the mid-1840s, the village of Conshohocken was a thriving community. Washington Street, named after General George Washington, was originally laid out as the main corridor in the village. Washington Street made sense, as it ran parallel to the Schuylkill River and canal. Industries and some retail outlets set up along the river and canal path.

But with the completion of the Schuylkill Canal in 1824 and the addition of small industry, the village grew in leaps and bounds. The Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad was built in 1835 and quickly played a prominent role in the village for both transportation and the shipping of goods.

The Conshohocken Post Office was established in 1836 and was located in the Ford Hotel and Train Depot.

In 1833, Conshohocken had one store, one tavern, a rolling mill, a gristmill and six dwellings. A census from the 1830s identifies the homeowners as David Harry, Cadwallader Foulke, Isaac Jones, Dan Freedley and C. Jacoby. While not mentioned by name, it is believed that Edward Hector was the sixth homeowner in the village. Conshohocken also had its first bridge over the Schuylkill River, a covered bridge owned and operated as a toll bridge by the Matsonford Bridge Company.

In the 1840s, the job market grew with the addition of Stephen Colwell opening up his blast furnace in both Conshohocken and Plymouth Township. Colwell's lime was a product needed by the Wood Company. Colwell's limestone quarries in Plymouth Township and James Wood & Son Iron Mill increased the job market. With the additional jobs came the workers and their families.

With the addition of residents came retail. The well-traveled paths running through the village quickly became roadsâdirt roads, of course. Coupled with the increased river and canal traffic, along with the railroad, transient workers followed. Retail businesses like John Pugh's Flour, Feed and Grocery Store, blacksmith shops, clothing stores, hardware stores and a few service shops pushed up the hill to Fayette Street.

It wasn't long before lawlessness followed. No one was responsible for repairing the washed-out dirt roads following a hard rain. With no rules or laws to govern the people, it became clear that it was time to incorporate.

Conshohocken, the First Hundred Years

I

NCORPORATION

, I

T

R

EALLY

S

TARTED IN

N

ORRISTOWN

The first incarnation of the United States Post Office was established by Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia in 1775 by a decree of the Second Continental Congress. The Conshohocken Post Office was one of the early offices established in 1836, outside city limits. It was located in the Ford Hotel and Train Depot located on the east side of the new covered bridge, alongside the train tracks and canal. In the early 1830s, the hotel and train depot were the hub of activity in the village.

By the mid-1840s, industry was growing. The increased industry brought jobs into the village, and with the jobs came families. That led to needed retail and service stores. During this decade, members of the busy Conshohocken village started talking about incorporation, recognizing the need for a governing body in the town.

In 1848, five members of the village were selected to apply for a charter of incorporation and select a name for the town. James Wood, James Wells, Isaac Jones, David Harry and Cadwallader Foulke were selected to complete the incorporation proceedings.

The five members of the committee were a diverse group. James Wood, owner and manager of the J. Wood & Sons Company, was selected chairman of the committee. James Wells was the proprietor of the Ford Hotel and Railroad Depot and for a time served as Montgomery County sheriff. Isaac Jones was president of the Matsonford Bridge Company, a privately owned toll bridge, until 1886, when Montgomery County purchased the bridge. David Harry was a gristmill owner and operator who also owned a large chunk of property in the village, and Cadwallader Foulke was a farmer in Plymouth Township on the border of the Schuylkill River whose land reached into the Connaughtown section of Conshohocken.

The 5 members of the incorporation committee represented the 727 residents of the village. With the residents' approval, the 5 men met in Norristown at the Montgomery Hotel in 1848 and decided on three possible names for the borough. They agreed to write the three names on separate slips of paper and drop them into Isaac Jones's beaver hat. According to the writings of Samuel Gordon Smyth (1859â1930), an early author for the Montgomery and Bucks County Historical Societies, it was James Wells who scribbled out “Conshohocken” on a slip of paper and dropped it into the hat. The other two names submitted were “Riverside” and “Wooddale.” The committee agreed that the third name drawn from the hat would be the name used for incorporation. Smyth reported that James Wells had the honor of drawing the three names, the third being “Conshohocken.”

On May 15, 1850, Conshohocken became the third borough in Montgomery County, following Norristown, established in 1812, and Pottstown, 1815. Pennsylvania's governor, William Fraeme Johnson, signed the document of incorporation, and on May 18, 1850, the incorporation papers were delivered by train on the Philadelphia, Norristown & Germantown line.

Several hundred residents (nearly the whole town) waited anxiously at the Conshohocken depot on May 18, when the train pulled into the station on time and the conductor of the train handed the sack of mail to the Conshohocken postmaster, who reached in and pulled out the official papers of incorporation. In turn, the postmaster handed the incorporation papers to Conshohocken's first burgess (mayor), John Wood, son of ironmaster James Wood, who officially announced to the cheering residents that they now lived in the borough of Conshohocken.

ET

'

S

H

ONOR

E

DWARD

“N

ED

” H

ECTOR

Edward “Ned” Hector came to settle in Conshohocken in 1827, long after his honorable discharge from the American Revolutionary army. Hector was one of Conshohocken's early settlers and the first known African American resident of this borough. Hector settled into a log cabin that at that time was on the outskirts of the village, located on the corner of what was to become Harry Street and Barren Hill Road, a block off the main path (Fayette Street).

Edward Hector was a private in Captain Hercules Courtney's company of Pennsylvania Artillery, mustered on March 10, 1777, by Lord Sprogell, a commissary general of musters.

In September 1777, Private Hector, in the military just six months, faced a life or death situation at the Battle of Brandywine. At that battle in Chester County, Captain Courtney's troops came under heavy fire, and many casualties were suffered, including one of Hector's contemporaries, John Francis. Francis, a fellow African American Patriot from Pennsylvania, lost both his legs at the Battle of Brandywine. Francis served under Captain Eppel and Colonel Craig and was pensioned out of service less than a year later.

Under heavy fire and many casualties, all troops were ordered to abandon their posts and retreat in an effort to save lives. Private Hector, an ammunition wagon driver, disobeyed the order to retreat and alone worked his way back onto the battlefield. Under heavy enemy fire, Hector recovered his team of horses and hitched the ammunition wagon, stopping to gather weapons left behind by the soldiers who had fallen victim to enemy fire.

Hector's heroics saved the day for the American forces and allowed the troops to recover and prevent the British from benefiting from the ammo wagons and supplies. Hector's heroism was noted in the history of the Revolutionary War records and can be found in the Pennsylvania Archives.

Edward “Ned” Hector passed away in January 1834, and his obituary, found in the

Norristown Register

from January 15, 1834, read in part:

Edward Hector, a colored man and veteran of the Revolution. Obscurity in life and oblivion is too often the lot of the worthy, they pass away and no “storied Stone”perpetuates the remembrance of their noble actions. The humble subject of this notice will doubtless share the common fate. He has joined the great assembly of the dead and will soon be forgotten, and yet, many a monument had been “reared to some proud son of earth” who less deserved it than poor old Ned. His earlier and better days were devoted to the cause of the American Revolution; in that cause he risked all he had to risk his life and he survived the event for a long lapse of years to witness the prosperity of a country whose independence he had so nobly assisted to achieve, and which neglected him in his old age

.