Reflections (30 page)

Authors: Diana Wynne Jones

In his stinginess, my father allowed us one penny a week pocket money. Money for anything else you had to ask him for. Looking back, I see I accepted this, partly because I thought it was normal and knew I wasn't worth more, but also because asking for money at least meant he spoke to me while he was inquiring suspiciously into the use of every penny. He also allowed me to darn his socks for sixpence a pair (by this stage I was sewing clothes for myself and my sisters and doing the family wash in spare moments). My sisters, however, rebelled at their poverty and bearded my father in his office. Groaning with dismay, my father upped our allowance to a shilling a week when I was fifteen, on condition that we bought our own soap and toothpaste. A tube of toothpaste cost most of two weeks' allowance. Isobel and I were by then civilized enough to save for it. Ursula squandered her money.

Ursula always took the eccentric way, particularly over illness. The cardinal sin we could commit was to be ill. It meant that someone grudgingly had to cross the yard with meals for us. My mother usually made a special trip to our bedsides to point out what a nuisance we were being. Her immediate response to any symptom of sickness was to deny it. “It's only psychological,” she would say. On these grounds I was sent to school with chicken pox, scarlet fever, German measles, and, for half a year, with appendicitis. Luckily the appendix never quite became acute. The local doctor, somewhat puzzled by my mother's assertion that there was nothing wrong with me, eventually took it out. He was an old military character, and in keeping with the rest of his life, he had only three fingers on his right hand. I still have a monster scar. I had the appendix in a bottle for years, partly to show my mother the boils on it and partly to live up to the title of semidelinquent. But Ursula, having concluded that “only psychological” meant the same as “purely imaginary,” deduced that it was therefore no more wrong to pretend to be ill than to be really ill. She drew on her strong acting talent, contrived to seem at death's door whenever she was tired of school, and spent many happy hours in bed.

Â

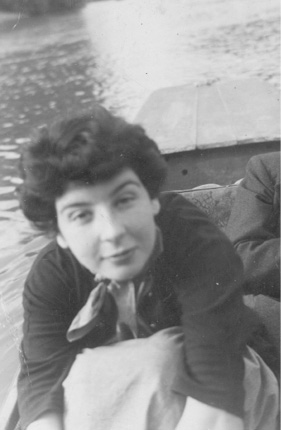

Diana's sister Ursula

Â

Diana's sister Isobel

Â

I put some of the foregoing facts in

The Time of the Ghost

, but what I think I failed to get over in that book was how close we three sisters were. We spent many hours delightedly discussing one another's ideas, and looked after one another strenuously. For example, when I was fourteen, Isobel was told by the Royal Ballet School that she could never, ever make it as a ballet dancer. Her life fell to pieces. She had been told so firmly that she was a ballerina born that she did not know what she was any longer. She cried one entire night. After five hours, when we still could not calm her, I crossed the yard in my pajamasâit was rainingâto get parental help. A mistake. My mother jumped violently and clutched her heart when I appeared. My father ordered me back to bed, despite my explanation and despite the fact that we had been ringing our recently installed emergency bell before I went over. I trudged back through the rain, belatedly remembering that my mother hated giving sympathy. “It damages me,” she had explained over my appendix. Ursula and I sat up the rest of the night convincing Isobel that she had a brain as well as a body. We were close because we had to be.

This solidarity did not hold so well when our parents laughed at us. I became very clumsy in my teens and they laughed at anything I did that was not academic. Perhaps they needed the amusement, because, for the next year, my father sickened mysteriously. When I was fifteen, he was diagnosed as having intestinal cancer. To my misfortune, something painful went wrong with my left hip at the same time, so that I could only walk with a sailorlike roll, causing much mirth. It was the beginning of multiple back troubles which have plagued me the rest of my life, but no one knew about such things then. The natural assumption was that I was trying to be interesting because my father was ill. It is hard to express the guilt I felt.

My father, full of puritanical distaste, weathered that operation. He developed secondary cancer almost at once, but that was not apparent for the next three years or so. Once he had recovered, it occurred to him that I would need special tuition if I were to go to Oxford as planned. The Friends' School was not geared to university entrance. Academic ambition vied in him with stinginess. Eventually, he approached a professor of philosophy who had just come to live in Thaxted with his wife and small children and asked him to teach me Greek. In exchange, my father offered the philosopher a handmade doll's house that someone had given my sisters. My sisters loved the thing and had kept it in beautiful condition. But the philosopher accepted the deal, so no matter what their feelings, the doll's house was given away. In return, the philosopher gave me three lessons in Greek. Then he ran off with someone else's wife. I must surely be the only person in the world to have had three Greek lessons for a doll's house.

After that, pressure mounted on me to succeed academically. In my anxiety to oblige, I overworked. I did nothing like as well as was expected. I did scrape an interview at my mother's old college. There a majestic lady don said, “Miss Jones,” shuddering at my plebeian name, “you are the candidate who uses a lot of slang.” She so demoralized me that, when she went on to ask me what I usually read, I looked wildly round her shelves and answered, “Books.” I failed. At the eleventh hour, I applied for and got a place at St. Anne's College, Oxford, where I went in 1953.

It was not a happy time. When I got there, I found that John Ruskin had taken belated revenge for the rubbed-out drawings: I had to share a vast, cold studio (which Ruskin had once occupied) with a girl who required me to wait on her hand and foot. And my father died after my first term there. I had to stay at home to see to his funeral, and spent the rest of my time at Oxford in nagging anxiety for my sisters, who were not finding my mother easy to live with. However, C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien were both lecturing then; Lewis booming to crowded halls and Tolkien mumbling to me and three others. Looking back, I see both of them had enormous influence on me, but it is hard to say how, except that they must have been equally influential to others too. I later discovered that almost everyone who went on to write children's booksâPenelope Lively, Jill Paton Walsh, to name only twoâwas at Oxford at the same time as me; but I barely met them and we never at any time discussed fantasy. Oxford was very scornful of fantasy then. Everyone raised eyebrows at Lewis and Tolkien and said hastily, “But they're excellent scholars as well.”

Â

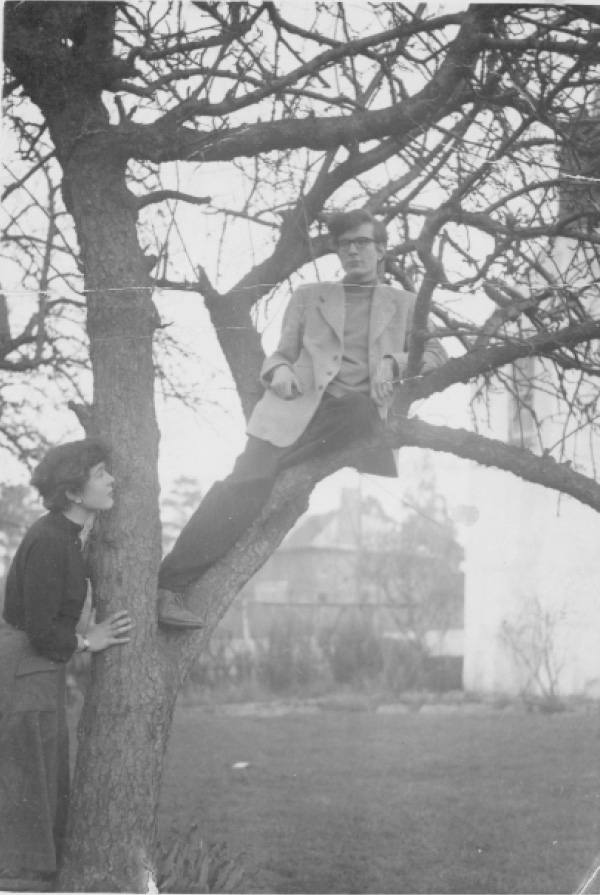

Diana's husband, John, with Diana looking on, 1955

Â

Let's go back now to the empty swatch of time before I went up to Oxford, when my father was periodically at home between times of being a guinea pig at an early and unsuccessful form of chemotherapy. I have not said much about the young people who came to Thaxted on courses, because most of them were mere transients, but there were some who came often, some my own age, with whom we became firm friends. One was in love with Isobel (many people were), and he was coming to the house with ten friends to relax after doing finals at Oxford. Now this was an occasion comparable to the time when I was eight and knew that I would be a writer. As soon as I heard they were coming, I was seized with unaccountable excitement. I raced round helping get ready for them and made the tea far too early. They arrived while I made it. In the small hall outside my father's office I ran into a cluster of them talking with my father. One of them said, “Diana, you know John Burrow, do you?”

I sort of looked. Not properly. All I got was a long beige streak of a man standing with them in front of the old Arthur Ransome cupboard. And instantly I knew I was going to marry this man. It was the same calm and absolute certainty that I had had when I was eight. And it rather irked me, because I hadn't even looked at him properly and I didn't know whether I

liked

him, let alone

loved

him.

Luckily both proved to be the case. The relationship survived two years at Oxford when John was a graduate student, and a third year when he was a lecturer at King's College, London. It also survived my mother's impulsive purchase, after my father died, of a private school in Beeston outside Nottingham, in a

very

haunted house. We moved there in the summer of 1956. I had been ill all that year, but after four months of listening to invisible footsteps pacing the end of my bedroom, I went to Granny, who was living in Sampford (near where the angel appeared to the gardener), in order to be married to John in Saffron Walden, in a thick fog, three days before Christmas 1956. There are no photographs of the wedding because, as my mother explained, her own wedding was more important. She married Arthur Hughes, a Cambridge scientist, the following summer.

John and I lived in London until September 1957, where I seemed unemployable. I used the time to read Dante, Gibbon, and Norse sagas. Then we moved back to Oxford to a flat in a large house on the Iffley Road, with another family downstairs who became our lifelong friends. Meanwhile, Ursula failed all her exams in protest against academic pressure and made it to drama school. She is now an actress. Isobel was at university in Leicester, working grimly for a good degree, when my stepfather turned her out of his house. She arrived on our doorstep, shattered, around the time I discovered I was pregnant, and was living with us when my son Richard was born in 1958. She stayed with us until my next son, Michael, was born in 1961, and was married from our flat. Her husband is an identical twin. John, who gave Isobel away, was mightily afraid of handing her to the wrong twin. She is now one of the few women professors in England. Ursula and I always think we did a good job of persuading her she had a brain.

Â

Diana with her Anglo-Saxon tutor, Elaine Griffiths, and John, 1955

Â

My third son, Colin, was born in 1963. My aim, from this time forward, was to live a quiet lifeânot an easy ambition in a house full of small children, dogs, and puppies. During this time, to my undying gratitude, John and my children taught me more about ordinary human nature than I had learned up to then. I still had no idea what was normal, you see. After that I found the experiences of my childhood easier to assimilate and could start trying to write. To my dismay, I had to learn

how

âso I taught myself, doggedly. At first I assumed I would be writing for adults, but my children took a hand there. First Michael threatened to miscarry. I had to stay in bed and, while I did, I read

The Lord of the Rings

. It was suddenly clear to me after that that it was

possible

to write a long book that was fantasy. Then, as the children grew older, they gave me the opportunity to read all the children's books which I had never had as a child, and what was more, I could watch their reactions while we read them. Very vigorous those were too. They liked exactly the kind of booksâfull of humor and fantasy, but firmly referred to real lifeâwhich I had craved for in Thaxted. Somewhere here it dawned on me that I was going to have to write fantasy anyway, because I was not able to believe in most people's version of normal life. I started trying. What I wrote was rejected by publishers and agents with shock and puzzlement.