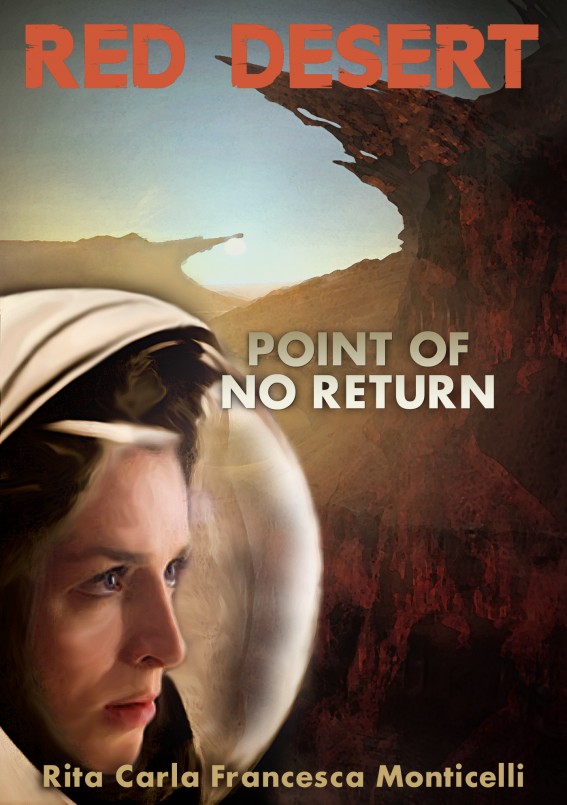

Red Desert - Point of No Return

Read Red Desert - Point of No Return Online

Authors: Rita Carla Francesca Monticelli

Tags: #mars, #space, #nasa, #space exploration, #space adventure, #mars colonization, #colonisation, #mars colonisation, #mars exploration, #space exploration mars, #mars colony, #valles marineris, #nasa space travel, #astrobiology, #nasa astronaut, #antiheroine, #space astronaut, #exobiology, #nasa mars base

Red Desert –

Point of No Return

Rita Carla Francesca

Monticelli

Copyright 2014 Rita

Carla Francesca Monticelli

Smashwords Edition

Book One of the “Red Desert” Series

Table of

Contents

Do you want to know what happens

next?

More books by Rita Carla Francesca

Monticelli

Do you want to keep updated on the next

publications?

Book 1

Point of No

Return

Original title:

Deserto rosso - Punto di non ritorno

© 2012 Rita

Carla Francesca Monticelli

Translation by:

Rita Carla Francesca Monticelli (© 2014)

Translation

revised by: Martina Munzittu, Richard J. Galloway, and Julia

Gibbs

Cover: © 2014

Alberto Casu

and Rita Carla Francesca Monticelli

Important note to the

reader

: This book is

written in British English.

I closed the airlock

door with a quiet thud and I locked it, knowing it might have been

for the last time. Outside it was still dark, just before dawn. The

instant the sun peeked out over the horizon its pale light would

hit the plains, creating long shadows.

I stood for a moment

looking at the stars through the glass, while the valves let out

some air to equalise the pressure with the outside. My suit, which

at first almost adhered to my body, was now expanding, giving me a

clumsy look.

The pressure balance

was reached and the exit door opened. Even though the suit was

heated, I perceived a huge difference in temperature. It could rise

well above ten degrees Celsius on a summer’s day, but it could drop

to minus ninety at night. And the hours before dawn were always the

coldest.

I switched on the

torch and went out, moving with caution. I hoped nobody had seen me

leave. Robert was lost in dreamland and had certainly no intention

of getting up at dawn, but Hassan, in spite of all that had

happened, carried on with the mission, especially now that he was

in charge.

He kept repeating that

in a few months more personnel and materials would arrive. I was

not convinced. Yet another major failure was looming and, at the

moment of need, those in Houston would come out with another

excuse.

Despite the heavy load

I was carrying, I walked with ease. With gravity a little more than

one third of Earth, everything was lighter, and thanks to my

experience over the years I was accustomed to moving with skill on

a rough terrain, even when wearing that uncomfortable suit.

I opened the hatchback

of a rover and loaded my provisions; then I climbed into the front

of the vehicle and activated the pressurisation. The life support

pumps pushed the gasses inside, creating the correct mixture for

breathing. When the green light came up on the dashboard,

indicating the process was complete, I removed my helmet and suit.

I laid them in the back, settled myself in the driving seat and

fastened the seatbelt. As soon as the engine started, an alarm

would go off inside the station, alerting them to the unexpected

activation of one of the two rovers.

There was still time

to go back. I just had to don my suit again, return to my quarters

and climb back into bed. Nobody would notice. But, even if my act

might appear senseless, to me it seemed the most reasonable thing

to do. There was nothing more for me in the station, beside pure

survival. Perhaps not even that certainty.

I studied the data

gathered the evening before on the on-board computer screen. It

wasn’t much, but it was all I had. I took a deep breath, and then

turned on the engine and put my foot down. I was moving towards

another certainty: that of my death. But I had started doing that a

long time earlier, when I accepted the invitation to join the

mission.

“Twenty-nine minutes

to the point of no return.”

The synthesised voice

of the on-board computer sounds again inside the rover. In about

half an hour I will pass the point of no return. The oxygen tank,

together with the carbon dioxide filters, provides breathable air

for one person for a maximum of fifty hours, and I’m about to pass

the twenty-fifth, this means that I won’t have enough to come back

to Station Alpha.

Not that I care, at

this stage.

I try to figure out

how to stop the alarm from beeping every minute, and wonder why

rovers aren’t equipped with an oxygen production system like the

one in the station. The chemical plant extracts this gas from the

carbon dioxide-rich air of Mars, releasing carbon monoxide outside

as waste gas. Why am I thinking this nonsense? Such an apparatus

would occupy too much space, reducing that available inside the

vehicle and making it even slower; it would also require excessive

energy.

The main feature of

these rovers is their agility, to the detriment of the operating

range. On the one hand, fifty hours seemed a sufficient amount of

time for any sortie we had to make in that first stage of our

mission. But actually, they reduced our chances of extending the

area of the planet we could explore. For people like us, with an

average age of thirty-five, who had to spend the rest of their

lives on Mars and who had nothing else with which to occupy their

time, it was a huge limitation.

It’s true that Mars’s

diameter is about half of the Earth’s, but the lack of oceans makes

the explorable surface comparable to the sum of all lands above sea

level of our planet. Hence plenty of places to visit, and even if

at first sight they may seem monotonous with all that dark red,

they hide countless wonders. And we chose to be the first

colonisers of this new world to observe them in person.

In over one thousand

days in the Lunae Planum, we scoured most of the area surrounding

the station within a radius of a little more than three hundred

kilometres. It’s quite impractical to go any further with a vehicle

that can hardly reach twenty-five kilometres per hour, but most of

time travels much slower, especially considering that each sortie

requires at least two persons, for safety reasons. Since there

wasn’t any particular hurry, NASA provided us with the minimum

equipment needed to carry out a series of scientific

investigations, which requires long periods of time and has brought

rather inconclusive results. Beside the geological studies, our

main mission is to find proof of a past life on the planet, though

I’m referring to very simple forms, like bacteria, which would

demonstrate that Earth isn’t unique in the solar system in this

context.

In the first nine

hundred and ninety-five days we were not lucky; we hoped to receive

new material from NASA in order to perform more accurate studies

and maybe push ourselves a bit further. Actually it should have

already arrived three hundred days ago, but a series of technical,

and most of all political, problems delayed its launch. Now we are

waiting for a new launch window, which occurs approximately every

two of Earth’s years, corresponding to one Martian year. This

setback hasn’t had a good impact on the group’s mood, already

affected by the prolonged forced cohabitation. However, we couldn’t

imagine what happened next.

I am able to switch

off that annoying alarm, at last. I have a bigger margin, thanks to

my suit’s endurance, which is about ten hours. This gives me a

certain degree of self-confidence, at least for now. I still have

the means to go back, so for the next four hours I’m just going to

enjoy the journey.

I’m postponing the

inevitable. I have no intention of going back.

The landscape over the

past day has been too repetitive, a single, immense, red desert of

stones and dust, but I can make out some changes in the horizon

now. I smile at the sight. According to the on-board navigator I’m

reaching Ophir Chasma, the first one of a group of formations that

constitutes Valles Marineris, the most complex canyon in the solar

system.

If a person on Earth

must see the Grand Canyon at least once in a lifetime, a person on

Mars cannot miss Valles Marineris!

I’ve read so much

about this place since I was a child and it was one of the main

reasons why I decided to be part of this mission. I can’t die on

this isolated planet without seeing it first. And if I had stayed

at the station, I would no doubt have died. At least this way, if

it has to happen, I will be the one to decide when. In thirty-five

hours, if the suit’s reservoir is full.

Since I left I had no

time to check it. The rover had been prepared for a sortie before,

which was postponed indefinitely. I counted on that, when I

abandoned the station, but I was in such a hurry that I only

thought of bringing some food and water. I put the suit on and went

out without thinking about it too much. I didn’t want to risk

changing my mind.

Since the deaths of

Dennis and Michelle, while Robert spent almost all his time in an

altered state of mind, only I and Doctor Hassan Qabbani were active

in the station. And I didn’t trust Hassan.

I had always looked at

him with suspicion. I knew it was a prejudice and my opinion about

him was different for a while but then, when Dennis died, I had

started to think he had something to do with his disease, as well

as with what happened to Michelle. I perceived a certain falsity in

his look. I started to stay as far as possible from him. I spent

hours and hours working in the greenhouse and avoided touching the

NASA food portions, because Hassan handled our meals. I preferred

to eat the products I had cultivated with my hands and after a

day’s work I went back to my quarters, always locking my door.

“Anna, what’s going

on? Where are you going?” Hassan’s stirred-up voice said via the

radio, some minutes after I had left the station. I just ignored

him, but he continued for a while. “Whatever you are thinking,

please, come back and let’s talk. If you go on, you’ll die.”

Another suicide would decree the definitive failure of the mission.

That was his only real concern, not my well-being. “I’m coming to

get you!”

Those words sounded

menacing and I switched off the radio in reply, then I disconnected

the transponder. That way he couldn’t keep tracking me, if he lost

sight of me. The station was almost at the edge of the horizon

behind me, when I saw his vehicle moving in my direction. He had

used up some of the time to refuel it, but now he was on his

way.

I stepped on the gas.

The flat terrain allowed me to travel at maximum speed, but the

same applied to his rover. By moving so fast, I made myself even

more visible from a distance, because I lifted a cloud of dust.

There were no heights to hide me.

The chase went on for

an hour or so, during which time his vehicle seemed to come closer.

I realised he would catch me sooner or later, if he didn’t decide

to stop. But Hassan wasn’t the kind of person who gave up.

When I had left, the

air was quite clear and the sky was clear, but as I penetrated the

planum the wind became stronger, raising the thin dust that covered

the terrain everywhere. Soon I was facing a dense cloud, made even

darker by the poor light at that time of the day. I decided not to

turn on the headlights, but to stop and let the dust envelop me.

This way I would disappear from Hassan’s sight. Perhaps he would

decide against following me in the storm.

The atmosphere was

charged with static electricity and from time to time I glimpsed a

flash. I would have been scared in normal conditions. The storm

might have lasted for hours, halting my progress. I was in the

widest of the plains, but it wasn’t free of obstacles. If I had

gone on blindly, I would’ve risked damaging the rover and ending

this last journey well before its time.

I took the opportunity

to eat. I had brought with me the quantity of food needed for at

least two and a half days. If I had to die, I resolved to do it

with a full stomach.

Two hours had passed,

before the visibility improved at last. I turned on the engine

again and started to move forward. There was no trace of Hassan

behind me. I found myself hoping he’d had an accident while

attempting to reach me, but I knew him well enough to know he had

gone back to safety. Whatever his intention was, it couldn’t rival

his instinct for self-preservation. With a sigh loaded with fatigue

I tried to dispel that hint of malice, the result of my anger, but

the truth was that I needed to go on, to avoid the temptation of

giving up.