Red Capitalism (39 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

Source: China Bond and International Monetary Fund

Note: China’s public debt includes only the MOF, the three policy banks, and the MOR. The Special MOF bonds of 1998 and 2007 are included.

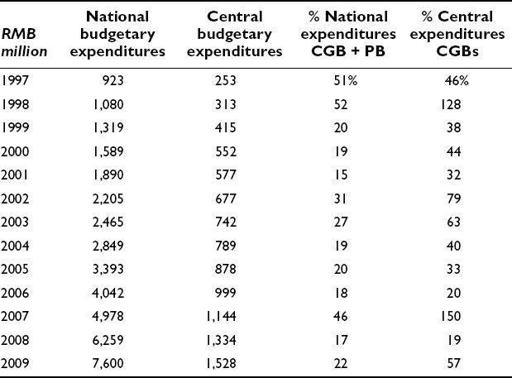

This picture of government borrowing is also illustrated by the amount of the annual national budget financed by new debt net of that issued to repay maturing bonds (see

Table 8.2

). Such debt issuance represents new money and finances new budgetary spending and, of course, it will add to the stock of a country’s obligations. In 2009, for example, net new bond issues from the MOF and the policy banks supported 22 percent of national expenditures, while new CGB issues alone financed 57 percent of central-government expenditures.

2

Similar to other Asian countries, China’s national budgets seem to be dependent on increasing amounts of debt.

TABLE 8.2

Net new-debt issuance as proportion of government expenditure, 1997–2009

Source: China Statistical Yearbook, China Bond; author’s calculation

Note: 2007 might be considered an anomaly given MOF’s RMB1.55 trillion Special Bond.

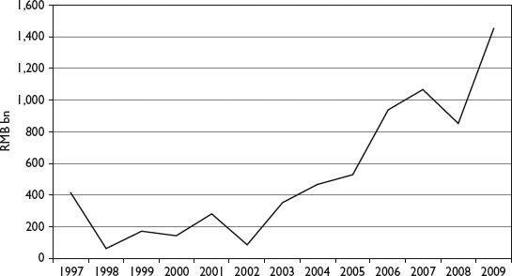

The budgetary dependence on debt can also be seen in the rapidly increasing amount of maturing central- and policy-bank debt. Over the period 2003–2009, the value of maturing MOF and policy-bank bonds grew at an annual compounded rate of 26.5 percent. These bonds were all refinanced; that is, rolled over into the future (see

Figure 8.3

). Net new debt plus debt issued to repay (and roll over) maturing debt equals the total amount of debt issued by China each year. Both add to the stock of China’s outstanding public debt.

FIGURE 8.3

Amount of MOF plus policy-bank debt rolled over, 1997–2009

Source: China Bond

Note: Retired debt is calculated as a function of year-end depository balances and annual new debt issuance.

It might be the case that this debt machine is not fully understood by China’s most senior leaders or they may be aware only of the more narrowly defined levels reported in the media. China’s public-debt figure is typically presented as only MOF obligations, its most narrow definition. It is unlikely to be a coincidence that of the total of China’s domestic debt obligations, only one percent is held directly by the end-investor: savings bonds. Aside from a minimal amount held by foreign banks and QFII funds, all else is either held or managed by state-controlled entities, from banks to fund-management companies. As the CEO of ICBC explained, China relies on “indirect” financing to achieve its economic growth goals. This means that banks decide on behalf of depositors how, to whom and under what conditions to lend deposits out. In a capital-market model, there is less room for such an intermediary; the end-investor is independent of the debt or equity issuer and makes investment or divestment decisions based on considerations independent of the interests of the issuer or borrower. In China, this is not the case: the Party controls the banks and the banks lend, as directed, to state-owned entities.

This is precisely where China differs from Mexico of 1994, Argentina of 1999 and Greece and Spain today. Aside from trade finance, China does not borrow money overseas and, because of the non-convertibility of the RMB, offshore investors are overwhelmingly excluded from the domestic capital markets. Nor are foreign banks competitive in the domestic loan and bond markets, given their need to make an adequate return on capital. As a result, foreign banks rarely contribute more than two percent to total financial assets in China; after the lending binge of 2009, they now stand at 1.7 percent. The only other major entry point into the system, QFII, is a CSRC product that is directed at the stock markets rather than bond markets. In any event, the current total quota allocated is, at US$17.1 billion, a relatively small amount. Even if fully invested in bonds, this would still pale by comparison with outstanding bond obligations of US$1.87 trillion. There is simply no way that offshore speculators, investors, hedge funds or others can get at China’s domestic debt obligations and challenge the Party’s valuation of these obligations. In short, the closed nature of China’s financial markets suggests a deliberate government strategy based on a particular understanding of past international debt crises. China’s financial system is an empire set apart from the world.

CRACKS IN THE WALLS

The fact that it is well-insulated from outside markets does not mean that China’s finances are crisis-proof. The system can be disrupted by purely internal factors, as it clearly has been in the past. Take, for example, household savings, pension obligations and interest-rate exposure. Household savings are the foundation of the banks’ capacity to lend. The heroic savings capacity of the Chinese people is virtually the only source of non-state money in the game. Since 2004, China’s banks have enthusiastically expanded their consumer businesses to include mortgages, credit and debit cards and auto loans. What would happen to bank funding if the Chinese people learned how to borrow and spend with the same enthusiasm as consumers in the United States? Over the long term, this might be good for the economy and even for the banks. But in the short-to-medium term, it seems unlikely that the government will actively encourage American-style consumerism outside of the rich cities of the eastern seaboard. This, in itself, may be a source of great social instability as the more numerous relatives in the hinterlands become envious of leveraged lifestyles.

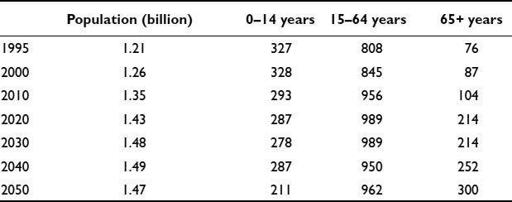

The overall demographic is pushing in the same direction. By 2050,

XinhuaNews

has stated, one out of four Chinese will be over the age of 65, but the actual number of retirees will be far greater (see

Table 8.3

). As the population ages, savings will be spent on old-age and health care. If the government continues to pursue growth through borrowing, the possibility of developing an economy based more on domestic consumption than export growth would seem low.

TABLE 8.3

China’s ageing population

Source: World Bank, Wall Street Journal Asia, June 15–17, 2001: M1

This also suggests that full funding for any national social-security program is a reform whose time is unlikely to come. Despite a strong beginning in 1997, the government continues to face difficulties in creating a standardized national program, on the one hand, and, on the other, sufficiently funding the programs it does have. Moreover, the funds it has under management lack suitable investment opportunities that can, with acceptable risk, yield returns higher than the rate of inflation. As noted earlier, at present only stocks and real estate, both highly speculative in nature, can potentially provide such a return. This harks once more back to the issue of China’s stunted capital markets. As the workforce ages, it appears likely that Beijing may have to fund any gap in such obligations largely through debt issuance.

3

The Ministry of Labor and Social Security has estimated this contingent liability to be only RMB2.5 trillion, whereas in 2005, the World Bank arrived at an estimate of RMB13.6 trillion. This puts the range at somewhere between 10 to 40 percent of China’s GDP; a very large obligation.

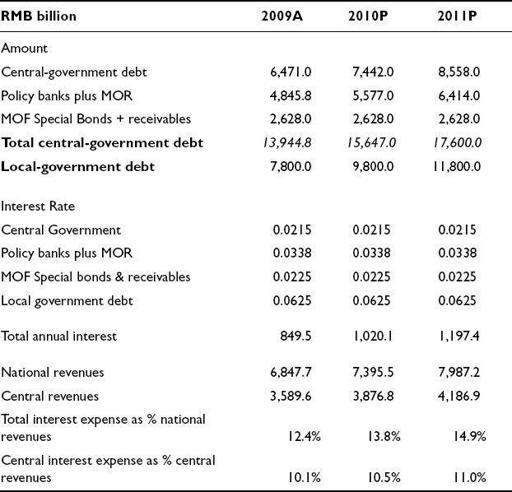

China’s debt strategy is also vulnerable to increases in interest. At some point, a heavy interest burden arising from increasing amounts of debt will limit the government’s ability to invest in new projects and grow the economy. Very rough estimates suggest that, as of FY2009, total interest expenditure on central- and local-government debt represents 12 percent of national budget revenues and may grow over the next two years to 15 percent (see

Table 8.4

). Inflation also poses a threat since it would both increase these government borrowing costs and put pressure on the valuation of bonds held on the banks’ books as long-term investments; valuation provisions would have to be made. This is why the PBOC finds it so difficult to raise interest rates, thus limiting the range of tools at its disposal to deal with inflation. Raising bank lending rates affect enterprise performance and have a knock-on effect in the bond markets. It also raises expectations of currency appreciation and, therefore, can encourage inflows of hot money. The PBOC last changed lending rates (downward) in late 2008 and has since relied solely on the previously little-used deposit-reserve requirement.

TABLE 8.4

Estimated interest expense of central and local debt, 2009–2011

Note: Assumes revenues grow eight percent annually; interest rates for central-government bonds reflect data in the ICBC FY2009 performance review; local-government debt interest rate assumed four percent over one-year deposit rate. Interest rates remain unchanged through 2011.

This reserve tool was first established in 1985. Used only four times prior to 2003, it has been employed 28 times since. It limits a bank’s capacity to make loans by removing a proportion of bank deposits: no funding, no loan. Currently the reserve ratio stands at 17 percent, which is close to its historic high of 17.5 percent; that is, 17 percent of all bank deposits sit in the PBOC’s accounts. Using this policy tool and making massive sales of short-term notes into the inter-bank market are all the PBOC can do to manage China’s money supply. It is little wonder that the central bank is vulnerable to political conservatives touting the efficacy of Soviet-style administrative intervention.

None of this means that China is in danger of default or even of a slowing in economic growth. If properly managed, there is no reason why China’s use of debt can’t continue for a long time. Witness the ongoing debt crisis in Europe, which has been a decade in the making. In the case of Greece, it appears likely that its financial accounts were managed to meet the requirements of entry into European Economic Community from the start. Yet it is only today, more than a decade later, that problems have emerged in public and markets have focused on them. Greece is an open economy with a thriving democracy. Think how long things may be obscured within China’s still-opaque economic and political system.