Red Capitalism (33 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

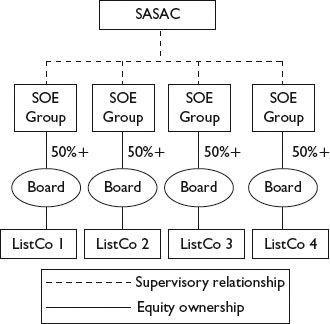

Despite its weak position in the state hierarchy, the SASAC was charged by the State Council with very significant responsibilities: 1) representing the state

as owner

of those central SOEs that together constitute the “socialist pillars” of the economy; 2) carrying out a human-resource function for SOE senior management; and 3) deciding where to invest dividends received from the SOEs. In each of these areas, the SASAC has had great difficulty exercising its authority, not simply because it is a sort of NGO, but also because its organizational relationship to its nominal charges was inappropriate.

First of all, SASAC has been unable to address the simple fact that it was not the owner of these SOEs (see

Figure 7.1

). Previously, the industrial ministries could make such a claim since they were a component part of the government and, in fact, oversaw the investment process in their subordinate enterprises. After the strategic assets of these enterprise groups were spun off into listed companies, the remaining SOE group companies became, in fact, the direct state investors in the National Champions. In contrast, SASAC was tacked on after the old ministry systems were eliminated. Secondly, while SASAC could oversee the appointment of management at the vice-president and CFO levels, the Party’s all-powerful Organization Department appoints the chairmen/CEOs. How can even a governmental entity exercise authority over enterprises whose senior management has been appointed by the Organization Department? These chairmen/CEOs do not report to a government minister; they report directly on a solid line into the Party system.

FIGURE 7.1

SASAC’s “ownership” and supervisory lines over the National Team

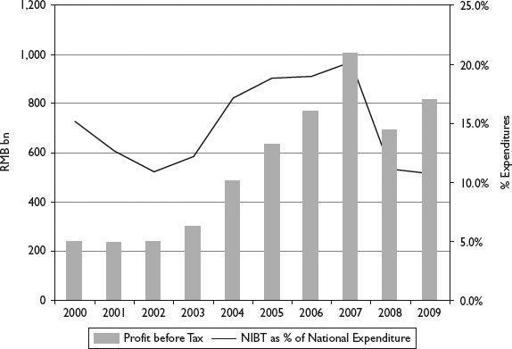

Finally, the delicacy of the SASAC’s position is well demonstrated by the fact that its “invested” companies have successfully resisted the payment of significant dividends, whether to the SASAC or the Ministry of Finance, despite a protracted struggle over the past few years. Even with a three-year “trial” compromise in place, reached in 2007 after years of wrangling, payments will be in the 5–10 percent range of post-tax profit, all of which has been used for projects that are equivalent to reinvesting into the SOEs. The profit made by these nominally state-owned enterprises is not small and in recent years has reached almost to 20 percent of China’s national budget expenditures (see

Figure 7.2

). This is a vast amount of money that would be better redirected at the country’s burgeoning budget deficit. Instead, because of their political and economic power, coupled with the ingenuous argument that they continue to bear the burden of the state’s social-welfare programs, the National Champions are able to retain the vast bulk of their earnings. The fact that the government is unable to access this capital is the best illustration of the power of these oligopolies.

FIGURE 7.2

Central SOE profit as a percentage of national budget expenditures

Source: 21st Century Business Herald 21 , August 9, 2010: 11

, August 9, 2010: 11

The architecture of the entire SASAC arrangement bears the hallmarks of the Soviet-style ministry system abolished by Zhu Rongji in 1998. In that system, SOEs reported directly to their respective ministries and were administratively managed by them (

guikouguanli ); the Party organization was their nerve system. The relationship between ministry and enterprise was all-encompassing, including investment, human resources and the deployment of capital and other assets. When the ministries were abolished, the line to the past was broken. The SASAC could not take their place, even though its structure was predicated on the thought that the old administrative management methods still worked. At best, the SASAC as presently constituted is rather like the State Council’s Department of Compliance. China in the twenty-first century is no longer built on the Soviet model.

); the Party organization was their nerve system. The relationship between ministry and enterprise was all-encompassing, including investment, human resources and the deployment of capital and other assets. When the ministries were abolished, the line to the past was broken. The SASAC could not take their place, even though its structure was predicated on the thought that the old administrative management methods still worked. At best, the SASAC as presently constituted is rather like the State Council’s Department of Compliance. China in the twenty-first century is no longer built on the Soviet model.

The SASAC model vs. the Huijin model: Who owns what?

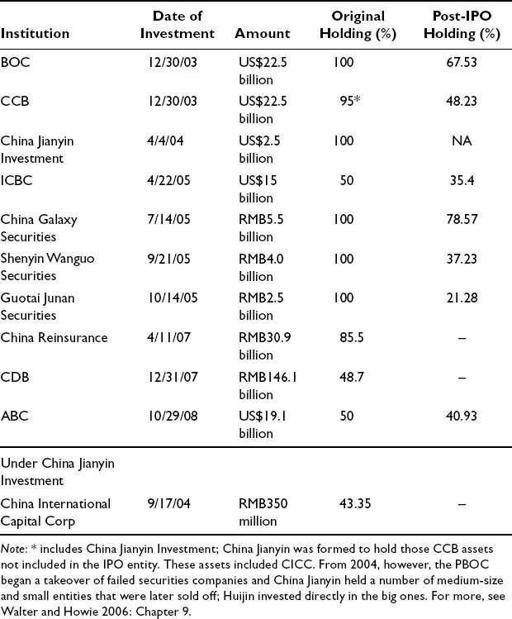

In deliberate contrast to the SASAC and taking full advantage of the international corporate model, the PBOC team created Central SAFE Investments (or Huijin), as a limited-liability investment company rather than a government body of any kind. Huijin was to be the critical part of the project to restructure the banks and was designed for the express purpose of investing directly in equity of the Big 4 banks. But it became much more than that (see

Table 7.2

). In late 2003, Huijin made cash investments totaling US$45 billion in CCB and BOC, acquiring almost 100 percent of their equity. In 2005, it invested a further US$15 billion in ICBC for a 50 percent holding.

TABLE 7.2

Huijin investments, the financial SASAC, FY2009

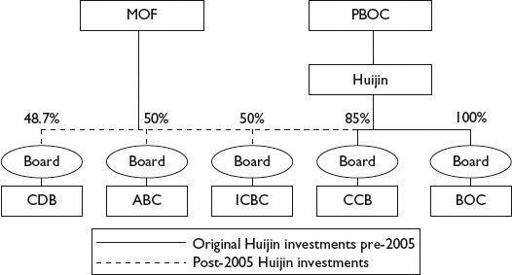

This direct holding was possible because of the “good” bank/“bad” bank approach described in Chapter 2. For SOE restructurings, the parent or group SOE that remained behind was effectively the “bad” bank and, at the same time, the majority shareholder of the “good” bank. Consequently, whatever dividends were paid went directly into the group’s coffers as the agency of the state. Removing non-performing assets to an entity owned by a nominal third party avoided this situation of having to create a holding company with the result that the state held direct equity interests in the banks. By 2005, Huijin had become the controlling shareholder on behalf of the state and enjoyed majority representation on the boards of directors of CCB and BOC and, together with the MOF, of ICBC, CDB, ABC and a host of other financial institutions.

In short, even after its acquisition by CIC in 2007 and no matter how it may be disposed of in 2010, it is in a position to directly control the decisions of these banks by a simple vote of its appointed directors at bank board meetings: senior bank management, having only vice-ministerial rank, had no excuses to prevaricate (see

Figure 7.3

). Of course, this all assumed that the Party agreed to Huijin’s positions, but, as Huijin’s continued operations over the years indicates, the structure has been viewed positively by the Party.

FIGURE 7.3

Huijin’s pre-IPO ownership and board control of the state banks

National Champions: The new government or the new Party?

The Party is able to ensure its control over China’s most powerful business groups by having the power to appoint their top management. Allowing the senior management of SOEs to retain their respective ranks within the Party

nomenklatura

after the dissolution of the ministries, however, created a fissure within the Party and government along business and political lines. In some sense, this was a pre-existing split in that families and friends of senior leaders had actively engaged in their own businesses since at least the early 1990s. But it is no longer simply a case of the sons and daughters of the rich and famous being out in the market selling influence. With access to huge cash flows, broad patronage systems and, in many cases, significant international networks, the senior executives of the National Champions can expect to succeed in lobbying the government for beneficial policies or even to set the policy agenda from the start. The sons, daughters and families now have institutional backing outside of the Party itself and this gives rise to questions over whether these business interests have, over the past decade, replaced the government apparatus or eroded the government from within. How accurate is the statement that “The business of China is business” and is this beneficial in a system of communist-style capitalism?

The case of Shandong Power

The notorious case of Shandong Power (

Luneng

) illustrates the consequences of Zhu Rongji’s elimination of the industrial ministries. In 2006, news was leaked out by

Caijing magazine that the state-owned electric utility in Shandong province and a number of its major adjunct enterprises had been completely privatized.

magazine that the state-owned electric utility in Shandong province and a number of its major adjunct enterprises had been completely privatized.

3

The company, a subsidiary of the State Power Corporation, was the largest enterprise in the province ahead of PetroChina’s subsidiary, Shengli Oil, Yanzhou Coal, and the well-known Haier Group. Its total assets of RMB73.8 billion (US$10 billion) and a total installed power-generating capacity of 360 gigawatts (second only to China Huaneng Group) had been acquired by two Beijing companies of uncertain background for a modest RMB3.7 billion (US$540 million). The name of the person behind the “acquisition” was well-known to market insiders and was (and remains) the president of a central-government enterprise group under SASAC, as well as an alternate member of the Central Committee.

Caijing , of course, did not reveal his name; there was no need.

, of course, did not reveal his name; there was no need.