Rasputin (14 page)

Authors: Frances Welch

But the stabbing in Pokrovskoye had, according to several accounts, added five years to Rasputin’s age. He began taking opium frequently and an old friend, who saw him at the time, said: ‘He walked around hunched over in a gown.’ Rasputin was shaken when he found himself unable to heal an old woman: ‘The Lord has taken my power away from me.’

It was not until his dramatic cure of his stalwart Anna Vyrubova that he felt his vitality returning. He was with Mossolov, Director of the Imperial Court, when he heard that Anna had been seriously injured in an accident. Mossolov had been trying to gain Rasputin’s support for a local government project and had already undergone one unproductive meeting: ‘I waited half an hour. At last he appeared, his face bloated, his hair unkempt.’ Following three bottles of wine, Mossolov appeared to carry the day as Rasputin said: ‘As for me, what can I do but give the idea my blessing.’

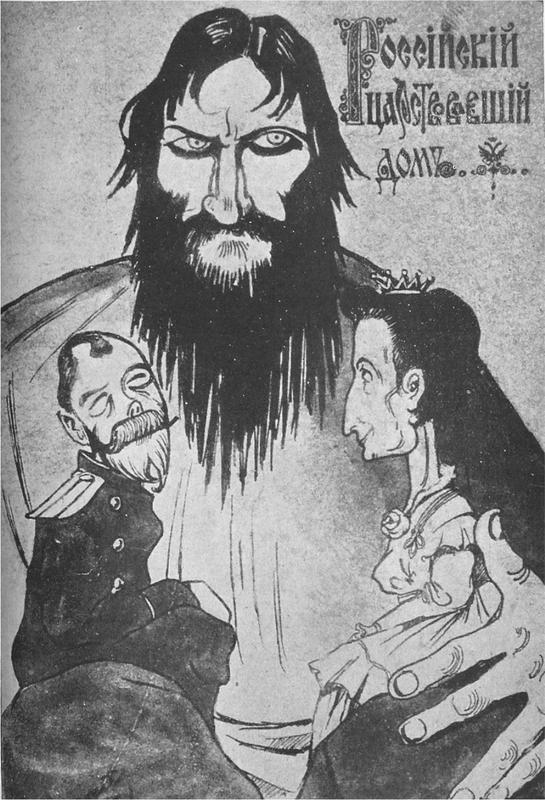

‘Russia’s Ruling House’ caricature by N. Ivanov. Cartoons were published of the Tsarina cavorting with Rasputin; schoolchildren sang lewd songs.

Mossolov felt, understandably, that the drunken meeting had been inconclusive and arranged to see Rasputin again, for dinner, in the house of a mutual friend. But this second discussion also went awry when, just as Rasputin was licking the soup off his fingers, he received one of his urgent phone calls. Was it his fascination with gadgetry, an over-blown sense of his own importance or some vision of the future that made Rasputin behave, in early 1915, as though he already owned a mobile phone? Wherever he went, he left numbers: he could always be reached.

On this occasion, he returned to the table white-faced and trembling: Anna, ‘Annushka’, had been in a train crash while travelling from Tsarskoye Selo to Petrograd. The train had come off the tracks in a heavy snowfall. He left for Tsarskoye Selo immediately, using a car belonging to another eminent supporter, Countess Witte, wife of the former Prime Minister. Upon his arrival, he discovered that Anna Vyrubova’s colossal legs had been irreparably crushed. He prayed for her before giving one of his bald but accurate pronouncements: ‘She will recover but she will always be a cripple.’ After praying he collapsed, as was his wont, but was furious to find himself ignored by ‘the Tsars’ and left to crawl back to Gorokhovaya Street under his own steam. He complained bitterly to Dounia.

Hours after his return, however, the Tsarina telephoned, full of gratitude. She sent flowers and ‘a basket of fruit so heavy that it had to be carried by two people’. Rasputin was delighted to find himself so much in favour again. But, as always, it seemed that any increase

in his popularity at Court was accompanied by a stepping up of hostilities beyond. Four days after his healing session with Anna Vyrubova, he was nearly run over by a sledge driven by ill-wishers from Tsaritzyn.

Later that year, a young man, Simoniko Pahekadze, announced that he wanted to marry the 17-year old Maria, who now boasted ‘enormous bright-coloured lips’ and a flirtatious manner. ‘She would pass the tip of her tongue over her broad, bright red lips in a kind of predatory animal movement,’ reported a fascinated visitor. But shortly after the couple’s engagement, it emerged that Pahekadze was among Rasputin’s enemies and primarily interested in killing his prospective father-in-law. He drew a gun on Rasputin but then, apparently finding his fingers frozen on the trigger, ended up firing into his own chest. He survived and was thenceforth banished from Petrograd.

I

n the last two years of his life, Rasputin found his wobbly ‘gift for knowing people’ taxed to the limit as murderous enemies vied with the favour-seekers and devotees for his attention. Despite his poor grasp of figures, he was now being courted by industrialists asking him to act as a business consultant. He developed a rudimentary taste for investments, toying with starting his own newspaper (‘they write such horrors about me’) and putting money into a newly emerging cinema with sound. Some of his actual, less ambitious

enterprises included various forms of mild extortion. He would charge, for instance, 2,000 roubles (roughly £200) for keeping a soldier from the front. In a one-off deal, he agreed to spring 400 Baptists from prison for refusing military service, for 1,000 roubles each. He demanded 250 roubles from a convicted forger for his release from prison. How much success he had with these ventures cannot be known exactly. And inevitably there were deals that went awry. An elderly baroness claimed Rasputin had swindled her out of 270,000 roubles after summoning Jesus in a seance: the case was not pursued, although an early investigation unearthed the florist who supplied a crown of thorns.

He was not short of income. On top of the government allowance of 10,000 roubles that he received each month, the syphilitic Protopopov paid him 1,000 roubles a month from his own pocket, for which doubtless he had his own mysterious political motivations.

Such was Rasputin’s prestige that, in January 1915, he was visited by Countess Witte, seeking promotion for her grandson. ‘The Countess Witte visited the Dark One on 8 and 25 January, both times wearing a thick veil,’ reported a security branch agent. ‘On 25 January she asked the doorman to escort her by the back stairway and gave him a three-rouble tip.’

It was in his role as businessman that Rasputin became embroiled in one of his worst scrapes. In March 1915 he arranged to meet prospective ‘clients’ at the Yar restaurant in Moscow. The meeting deteriorated when he began boasting that the Tsarina had sewn shirts for him. His bragging increased with drink, until he was

roaring that ‘the old girl’ had slept with him. Asked if he really was Rasputin, he dropped his trousers and waved his penis. With his penis exposed, he carried on chatting with several female singers, while distributing notes saying: ‘Love unselfishly.’

The eminent British diplomat, Robert Bruce Lockhart, who was attending an event at the Yar, later wrote in dismay: ‘As we watched the music hall performance in the main hall, there was a violent fracas in one of the private rooms. Wild shrieks of a woman, a man’s curses, broken glass and the banging of doors. Head-waiters rushed upstairs. The manager sent for the police… But the row and roaring continued… The cause of the disturbance was Rasputin – drunk and lecherous, and neither police nor management dared evict him.’

The police eventually took Rasputin away at 2.00am. The following day he left Moscow in disgrace, doubtless consoled by a crowd of ‘little ladies’ who gathered at the station to see him off. The business project under discussion at the Yar, it emerged, would have been lucrative for Rasputin, but sadly fell through; it concerned outsize underwear for the military.

The Assistant Minister of the Interior and Director of the Police, Vladimir Dzunkovsky, had already crossed swords with Rasputin. Now, following three months of inquiries into the incident, he handed a graphic report to the Tsar, who, somewhat at a loss, instructed Dzunkovsky to keep the report to himself. ‘The sovereign… listened very attentively, but did not utter a single word during my report,’ recalled the Assistant Minister. ‘Then he extended his hand and asked: “Is it written out?” I

removed the memorandum from the folder, the sovereign took it, opened his desk and put the memorandum inside.’ Disobeying the Tsar, Dzunkovsky promptly showed a second copy of the report to Grand Duke Nicholas and also to Prince Yussoupov’s future fellow conspirator, Grand Duke Dmitri. For this he was fired.

Rasputin was jubilant; as he had already told one of his policemen: ‘Your Dzunkovsky’s finished.’ But the young Grand Duchesses would have been disappointed to see him go: they were great fans of his repertoire of bird calls.

The Tsarina’s angry response was especially incoherent; it is hard to tell whether she was more exasperated with Dzunkovsky or her husband. ‘He acts as a traitor and not as a devoted subject who ought to stand up for the Friends of his Sovereign,’ she wrote to the Tsar. ‘You see how he turns your words & orders round – the slanderers were to be punished… ah, it’s so vile… If we let our Friend be persecuted we & our country shall suffer for it. Ah my love, when at last will you thump with her (sic) hand upon the table & scream at Dzunkovsky & others when they act wrongly – one does not fear you – they must be frightened of you.’

When Rasputin eventually saw the Tsar, he successfully defended himself with his usual pleas: it was hard for those seeking the path of truth and righteousness; he was a ‘sinful man’ but he couldn’t help it. ‘Despite my terrible sins, I am a Christ in miniature.’

Nikolai Sablin, the Commander of the Imperial yacht, the

Standart

, carried out a further investigation. He admitted later that he had been reluctant to mention

the incident at the Yar to the Tsarina as it had had a ‘morbid effect on her’. Sablin himself found tales of Rasputin’s debauchery hard to believe, particularly when they involved women in elevated circles: ‘It seemed impossible that any society woman, unless possibly a psychopath, could give herself to such a slovenly peasant.’

Rasputin’s supporters found various defences for his worsening behaviour. The Tsarina came to believe that an imposter was posing as Rasputin and misbehaving in clubs. Others insisted any deterioration was linked to mental and physical trauma resulting from his stabbing in Pokrovskoye. As for Rasputin himself, he always had a homily to hand: ‘It is wrong to pretend they [human desires] do not exist and to allow them through neglect to atrophy.’ Of saints he would add that they ‘turn to filth in order that, amid the filth, their aureole may shine with double brightness’.