Rasputin (12 page)

Authors: Frances Welch

It is hard to gauge what affect, if any, the Dowager's words had upon the Imperial couple. It seems very unlikely that either was truly grateful for the Dowager's âfrankness'. The Tsar's diary entry is particularly non-committal: âMama came for tea; we had a conversation with her about Grigory.'

But shortly afterwards, the Tsar asked the fearsome Mikhail Rodzyanko, President of the Duma, to launch an investigation into Rasputin's life. In the course of several subsequent inquiries, Rodzyanko would hear of at least one woman petitioner instructed by Rasputin to return in a décolleté dress in order to secure her husband's promotion. As Rasputin would put it: âAll right, I'll see to it. But come again tomorrow in an open dress with naked shoulders. Otherwise don't bother.'

Rodzyanko was under no illusion about the sensitive nature of his final report. Before seeing the Tsar, he steeled himself with a prayer in the Kazan Cathedral. The Tsar's response to Rodzyanko's brave denunciation is not recorded in any detail. But when Rodzyanko raised the thorny issue of women in the bath-house, the Tsar retorted that communal bathing was âaccepted among the common people'. Rodzyanko seemed to make headway when he produced a picture of Rasputin dressed as a priest and the Tsar commented: âThis time he's gone too far.' But the principal outcome of the report was to drive a wedge between Rodzyanko and the Tsar. The Tsar eventually refused to see him and cut him dead at a service commemorating the Battle of Borodino

in Moscow in 1912. As Rodzyanko explained grimly: âHis dissatisfation with me was my report on Rasputin.'

It was during this same year that the 24-year-old Englishman, Gerald Hamilton, the model for Isherwood's Mr Norris, paid Rasputin two visits. Hamilton saw nothing of any âdark forces' and was, in fact, deeply impressed by Rasputin, particularly when he saw him performing a cure on a young epileptic boy. âThe boy was brought forward by his mother and sat in a chair. Rasputin first looked at him; then he put his hands on him, muttering prayers. Later the boy twitched a lot, but Rasputin never took his hands off his chest. This huge man became paler and paler until finally the boy⦠got up and ran to his mother. It took about seven minutes in all.'

After the cure, Hamilton recalled that Rasputin collapsed dramatically into a chair proclaiming: âAll the good has gone out of me, and I must get new strength. I have been fighting the evil spirits in that poor boy.' The story is slightly undermined by Hamilton's recollection that the cure took place at Gorokhovaya Street when, in fact, Rasputin did not move there until 1914.

Hamilton remained resolutely enamoured of Rasputin; he was not in the least put out when he heard that Rasputin did not care for the English: âI considered it a great privilege to have seen undeniable proof of his extraordinary gift of healing. It may seem profane to mention Jesus Christ in any connection with Rasputin but for all I know God may choose odd vessels to do his work.'

As fresh attacks were launched in the Duma and at

Court, it may have struck Rasputin's beleaguered supporters that some vessels could be too odd.

B

ut in October 1912 an event occurred which raised Rasputin's stock at the Palace and, for a while, rendered him unassailable. He was on one of his frequent visits to Pokrovskoye at the time: âgoing for a little home', as the Tsarina put it blithely. The purpose of these endless returns was twofold: he appeased his detractors by keeping a low profile while gratifying his weakness for creature comforts and soft furnishings. He may even have welcomed a respite from the dizziness of his life in St Petersburg, with its unending array of colourful characters.

As he was walking along the River Tura with his daughter Maria, he suddenly clutched his head and told her something had happened to the Tsarevich Alexis: âHe's been stricken.' A couple of days later he received a telegram from Anna Vyrubova saying that Alexis was mortally ill in a hunting lodge at Spala, in Poland.

The Rasputins were in the middle of a family lunch when the telegram had arrived. Rasputin made one of his fierce gestures at the maid, Dounia, to stop doing dishes, while he left the room to pray. He was grey and sweating when he reappeared, but immediately set about composing a reply. He loved sending telegrams, not least because he could leave any awkward spellings to the telegraphist. He sent two messages: âThe Little

One will not dieâ¦. Do not let the doctors bother him too much.'

Alexis had injured his leg while jumping onto a boat. He seemed to have recovered, but the Tsarina had then taken him for a drive and the violent shaking of the carriage had brought on a stomach haemorrhage. His subsequent cries of pain were so heart-rending that the more sensitive servants resorted to ear-plugs. None of them would have known, at this point, that Alexis had haemophilia. His anxious doctors met regularly in Mossolov's room. As Mossolov recalled: âNone of the remedies which they prescribed sufficed to arrest the bleeding.'

The eight-year-old boy himself was prepared to die, instructing his despairing parents to bury him beneath a blue sky and build a monument. The Tsar reluctantly agreed to issue a news bulletin announcing that the Tsarevich was ill; bulletins were posted as far away as Siberia. A tent erected on the lodge lawn for worship was soon being visited by weeping Polish peasants. The fervent Father Vassiliev performed the last rites.

Alexis began to recover the day Rasputin's first telegram arrived from Pokrovskoye. The Tsarina was convinced that, without Rasputin's prayer, her son would have died. As she said to Mossolov: âIt's not the first time the

starets

[Holy Man] has saved his life.' The doctors were apparently confounded. One of them, Professor Federov, had at one point asked Mossolov's advice, asking whether he should risk experimenting without telling the Tsar or Tsarina. As Mossolov wrote: âProfessor Federov said: “Should I prescribe without saying anything?”' After the spectacular recovery, Mossolov asked Federov if he had applied some secret remedy; but Federov replied, tantalisingly, that even if he had, he couldn't have admitted it.

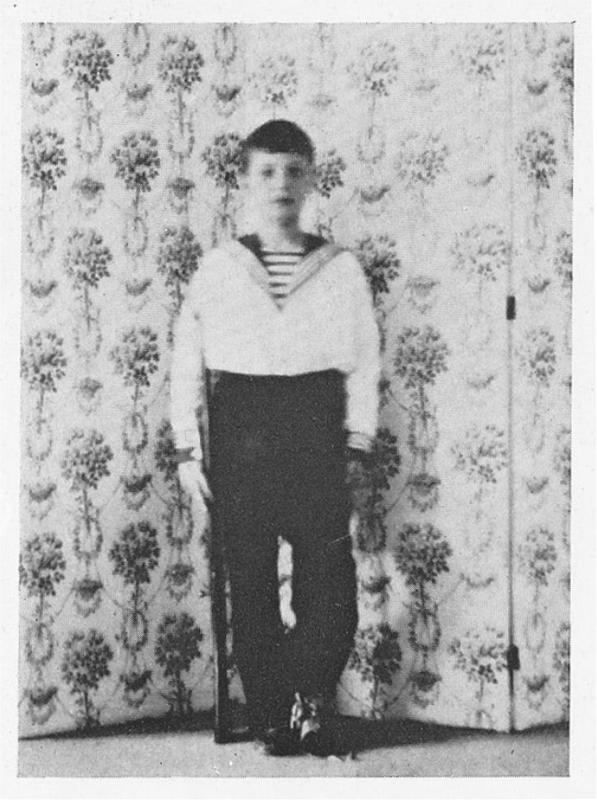

Alexis after Spala

Â

The Imperial Family

The Tsarevich's journey back to Russia was meticulously planned. The roads were smoothed between the hunting lodge and the station; the train to St Petersburg travelled at 15mph and never once used its brakes. Mossolov reported that the doctors at Spala were not consulted about the fragile Tsarevich's departure and were deeply upset to have found themselves so promptly sidelined. When the Tsar described the crisis to his mother, he made no mention of Rasputin's telegrams.

R

elations between âour Friend' and the Palace had never been closer. By the time the Imperial family reached St Petersburg, Rasputin and his two daughters had also returned. The Tsarina telephoned on arrival and Maria gushed: âMama, I have missed you.' The girl was ecstatic to receive a further call, from Anna Vyrubova, issuing a coy invitation for tea to meet âa certain family'.

The Tsarina's view of the Russian aristocracy as decadent had been formed during her first days in the capital. Coming originally from the quieter German Court of Darmstadt, she had been shocked by the loose society, all-night parties and flaunted love affairs: âThe heads of the young ladies of St Petersburg are filled with

nothing but thoughts of young officers,' she had sniffed.

Her misgivings resulted in the Imperial children's social lives being woefully restricted. Dr Botkin's son, Gleb, recalled that their only friends were the children of Alexis's sailor carer, Andrei Derevenko, and Rasputin's two daughters. The Grand Duchesses met the Misses Rasputin relatively late on, in 1912; but for Gleb, it was not late enough: he dismissed them as âveritable street urchins'.

In fact, Maria, now 14, had already been in St Petersburg for two years and was quite accomplished: able to play tennis, accompany herself singing and hold forth about fashion. Born Matryona, she had adopted the smarter name of âMaria': she might have been glad to distance herself from the ragged mystic, Matryona the Barefoot.