Rampage (21 page)

Authors: Lee Mellor

Considering that Valery Fabrikant qualified for every single one of these criteria, the unspecified “personality disorder” that Dr. Steiner proposed he suffered from was most likely narcissistic.

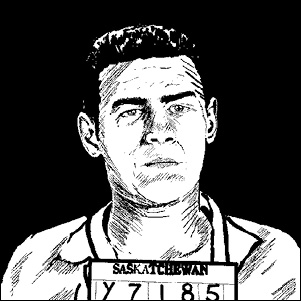

Robert Raymond Cook

Victims:

7 killed

Duration of rampage:

June 25, 1959 (mass murder)

Location:

Stettler, Alberta

Weapon:

Shotgun

Conduct Disorder

Robert Raymond Cook came screaming into the world of Hanna, Alberta, on July 15, 1937, the first-born child of eighteen-year-old Josephine Cook and her husband, twenty-eight-year-old Raymond Albert Cook. The marriage was a turbulent one, with Josephine constantly accusing Raymond of philandery. To complicate matters, she suffered from a number of illnesses, including a weak heart, and on September 16, 1946, died during reparative surgery on a twisted bowel. In the blink of an eye, nine-year-old Bobby found himself motherless and the sole object of Raymond’s attention. This claustrophobic emotional bond with his father lasted until the summer of 1949, when Raymond wed Bobby’s grade school teacher, Daisy May Gaspar. A son, Gerald, followed in February 1950 (the Cooks would go on to have four more children). That same year, the family relocated to the rural community of Stettler, 170 kilometres north of Calgary and 145 kilometres south of Edmonton. This sudden shift in family dynamic and location seemed to have a profound effect on the thirteen-year-old Bobby, who began showing signs of conduct disorder, a prerequisite for anti-social personality disorder. Though he was fond of breaking and entering, his crime of choice was hot-wiring cars to take on joy rides for “the excitement and adventure.”

[45]

Such was his knack for automobile theft that, at the age of fourteen, Bobby was sent to Bowden Reformatory. The institution did not live up to its name, and between the ages of thirteen and twenty-one, Bobby earned nineteen separate convictions, landing himself in Lethbridge Jail, then Stony Mountain Penitentiary. There, the 155-pound convict was groomed to be a welterweight boxer. Rather than earning himself a professional fighting career, Bobby ended up in Saskatchewan Penitentiary.

Fortune intervened on his behalf. To celebrate Queen Elizabeth II’s royal tour of Canada, one hundred non-violent inmates at the Saskatchewan facility were granted amnesty. On Tuesday, June 23, 1959, Robert Raymond Cook was among sixty prisoners released back into the public, and rode the bus from the Prince Albert penitentiary to Saskatoon, where he went bar hopping with prison buddy Jimmy Myhaluk. The next morning they caught a Greyhound to Edmonton, where Bobby slept off his hangover at the Commercial Hotel and Jimmy left for his parents’ home. Before heading to the Myhaluks’ for dinner, Bobby stopped by Hood Motors, where his car-coveting eyes fell upon a brand new white Chevrolet Impala convertible, its red upholstery beckoning like a pin-up girl’s lips. Entranced, he spoke with salesman Carl Thalbing about the possibility of exchanging a 1958 station wagon for the object of his desire. Bobby knew just where to find one.

Consistent Irresponsibility/Failure to Plan Ahead

Two days later, at 8:00 a.m. on Friday, June 26, Bobby returned to Edmonton in his father’s station wagon. At South Park Motors he attempted to trade the vehicle for something fancier, but was unable to successfully negotiate a deal with salesman Arthur Pilling. By 11:30 he tried his luck once more at the Hood dealership. Posing as his father, Raymond, who had a record of steady work experience, Bobby conned salesman Len Amoroso into letting him take the Impala for a test drive in exchange for the station wagon, a $40 down payment, and the promise that he would be back by 5:00 p.m. to fill out the necessary documentation. Of course, he had no such intentions.

Thirty hours and 720 kilometres later, Robert Raymond Cook was coasting through downtown Stettler when he was pulled over by Constable Allan Braden. Taken to the RCMP detachment, the young car thief came face to face with Sergeant Tom Roach. Hood Motors had contacted the Stettler police to inform them that a local man named Raymond Cook had bought a shiny new Chevy convertible and had forgotten to sign the paperwork. Well aware of Bobby’s criminal history, Sergeant Roach suspected he had impersonated his father and stolen the vehicle, but decided it was best to speak with Raymond himself before leaping to conclusions. Contacting the elder Cook by telephone proved to be more difficult than expected.

While searching the Impala, Roach discovered two suitcases stuffed with nightclothes, along with a metal box containing the Cook children’s birth certificates, Raymond’s bank book, and his marriage licence. Bobby explained to Sergeant Roach that his family had taken a trip to “somewhere in British Columbia” in hopes of purchasing a garage. Before they left, his father had instructed him to exchange the station wagon for the Impala. As Bobby had no identification, Raymond had lent him his own. Bobby assured them there was no cause for concern: everything would be satisfactorily explained when his father returned. Suspicious, Roach confined Bobby to a holding cell, anticipating that he would soon be charged with false pretenses. In the meantime, he drove to the Cooks’ four-bedroom bungalow, a mere two blocks from the station, but noted no signs of disturbance. Still, Roach had a nagging feeling that something was terribly wrong. At half past midnight, he returned to the dwelling with Constable Al Morrison. The two entered, scouring the darkness with their flashlights. They noticed that while the children’s shoes remained neatly under their beds, the sheets had been removed from the mattresses. If the Cooks had left for British Columbia, why had they done so barefoot and stripped the linens?

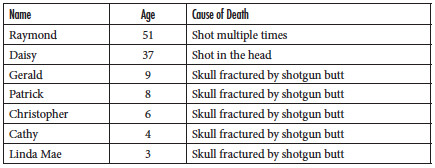

Intent on getting to the bottom of the mystery, five RCMP officers arrived at 11:00 a.m. to search the premises. The late-morning sun through the windows cast light upon the shocking truth: the walls and beds were caked with blood. Shards of a broken shotgun butt were mixed among clumps of brain, bone, and hair. The only trip the Cook family had taken was a screaming departure from this world. But where were the bodies? That answer came half an hour later, when the officers entered the adjoining garage at the back of the bungalow. Somebody had flattened a number of cardboard boxes, laying them like tiles across the filthy floor. Beneath the cardboard, the investigators discovered a second layer of wooden boards placed over a grease pit. Pulling away the planks, they gagged at the stench of decay rising from below. Among the discarded clothing, bedding, used car parts, and other junk, the bloated corpses of Raymond and Daisy Cook lay stacked upon their dead children — like seven sardines crammed into a two-by-four-foot oily tin. Raymond’s chest had been blown open by buckshot, while only fragments of Daisy’s skull remained — the remnants of a shotgun blast to the head. In a sickening twist, the children had each been bludgeoned to death with the butt of the weapon, as if sparing their suffering hadn’t been worth the ammunition. All seven victims had been slaughtered in their pajamas, their bedclothes lacquered to their green-blue bodies with grease. Whether they knew it or not, the men from the Stettler RCMP were gazing down upon Alberta’s worst familicide of the twentieth century.

Table 4: Victims of the Cook Family Massacre

Deceitfulness/Failure to Conform to Social Norms

The horrified officers got to work immediately. An inspection of the premises revealed Bobby’s bloodstained blue prison uniform concealed beneath a bed. The killer had made an unsuccessful attempt to scrub the spattered walls clean. Judging by the bloody mattresses, Raymond and Daisy had been shot fatally in their beds, before the boys — Gerald, Patrick, and Christopher — were battered to death. The lack of blood on Kathy’s and Linda’s linens implied the girls had fled their room when the gunshots began, but that their assailant had followed them into the living room, clubbing them to death like baby seals. He had then rolled all seven corpses into the filthy mass grave along with various other junk, and made a half-hearted attempt to conceal them. The pathologist estimated that the murders had occurred within the last twenty-four to seventy-two hours, placing the time of death between noon on Thursday, June 25, and noon on Saturday, June 27. However, the failure of Raymond and the children to show up for work or school on Friday seemed to indicate that they had been slaughtered either the previous evening or during the wee hours of Friday morning.

Further investigation revealed that a couple named Jim and Leona Hoskins had visited the Cooks until 9:00 on the night of Thursday, June 25. A witness named Arnold Filenko claimed to have seen Raymond give Bobby a lift soon after. It seemed an open and shut case: Robert Raymond Cook had arrived at his family’s home Friday night, mercilessly slaughtering them to steal their station wagon, which he then traded for the Impala. But Bobby had an explanation for everything. He had cadged a ride to Stettler with Walter Berezowski early on Thursday, June 25, arriving at 1:00 p.m. There he had loitered around town until 9:00 p.m., when his father came to pick him up. Robert and Ray went for a beer at a local bar, where their conversation soon turned to the possibility of buying a garage in British Columbia. Having agreed that it was an excellent idea, they parted ways. Bobby returned to the family home at 9:30 p.m., where the two men proposed their plan to Daisy, who seems to have got on board immediately. Bobby handed his father his blue prison-issued suit and approximately $4,000 in cash that he had dug up from a hiding place in Bowden the previous day, keeping a few hundred aside for himself.

*

This money was to be his contribution to the purchase of their garage. Raymond reciprocated by lending his automobile, wallet, identification, and car keys to Bobby so that he could swap the station wagon in Edmonton for the Impala. When the exchange was complete, Bobby was to drive the convertible back to Stettler and await a telephone call from his father with instructions to collect the rest of the family. Bobby claimed that when he left the house for Edmonton at 10:30 p.m., his father, stepmother, and siblings were alive and well. The following day, he successfully traded the vehicles and drove to Camrose, Whitecourt, and then back to Camrose again on some kind of aimless road trip. On Saturday he had been ticketed for driving with an open bottle of liquor in his car, before finally heading back to Stettler. At 7:00 p.m., he arrived at the little bungalow to find his family had left without him. Lingering for an hour or so, he drove downtown, where he was eventually stopped by Constable Braden. Unfortunately for Bobby, the police weren’t buying his story.

Charged with his father’s murder the following day, Robert Raymond Cook was sent by Magistrate Fred Biggs to be psychiatrically evaluated over a thirty-day period. While he was held at Ponoka Mental Hospital, Cook’s seven deceased family members were buried in a single grave in a Hanna, Alberta, cemetery on July 2 — his requests to attend denied. Then, on July 11, Bobby tore through a wire mesh window and escaped. Thus commenced one of the largest manhunts in Alberta history; with seventy-five police officers, two hunting dogs, and a light spotter plane searching the hillsides and farm fields around Ponoka. The authorities sensibly cautioned the public against picking up hitchhikers, but thumbing rides was hardly the fugitive’s m.o. Later that same day, a car Cook had supposedly stolen from the Ponoka area was found overturned in the tiny hamlet of Nevis, along with evidence of a break and enter at the town hall. Accompanied by a second spotter plane, a hundred RCMP patrollers spent Sunday searching the seventeen kilometres between Nevis and nearby Alix. It wasn’t until Monday that they picked up the fugitive’s trail, discovering a second stolen vehicle outside of Bashaw. Judging by the evidence, the police deduced that Robert had fled southeast to Stettler before veering north. By now, sixty soldiers from the Canadian Army Provost Corps were on his trail in jeeps and helicopters. When a farmer’s wife telephoned police around 3:00 p.m. Tuesday to report a shadowy figure lurking behind her barn, two police cruisers sped to her home. The property owner, Norman Dufva, greeted them upon arrival and led them to the area where his wife had sighted the trespasser. As they approached, a starved and dishevelled-looking Bobby Cook stepped out from his hiding place and surrendered. A consummate criminal failure, he had been on the lam for a mere seventy-four hours before being handcuffed and carted off to Fort Saskatchewan Jail.