Rampage (17 page)

Authors: Lee Mellor

In August 1864, Confederate disbursing agent Major Norman Walker gave Keith $40,000 to purchase pork from New York to be distributed to starving southerners. Keith returned with only sixty pounds of meat, blaming customs agents for confiscating the rest. He pretended to become embroiled in a legal battle to win back his client’s pork, keeping Walker’s money under the auspices of paying for his lawsuit. Eventually the wealthy Walker resigned himself to defeat, and Sandy Keith pocketed the money once again.

Around 1864, Keith’s modus operandi seems to have evolved further, switching from seeking compensation for lost cargo to sunken ships. That year, he tricked South Carolina dry-goods merchant H.W. Kinsman into entrusting him with the ownership papers for his ship, the

Caledonia

, which had sunk off the coast of Nova Scotia en route to Nassau. Keith collected the $32,000 in insurance, passing himself off as the true owner. Kinsman was furious, but without the paperwork to back his claim, he was legally impotent. The next to fall prey to Keith’s insatiable greed was his associate, Montreal businessman Patrick Martin, who was known to dabble in the blockade-running racket. Martin was an associate of the reputed southern actor, and later presidential assassin, John Wilkes Booth. As part of an elaborate scheme to kidnap Abraham Lincoln, Martin had promised Booth he would ship his wardrobe past the Union blockade to the south. Along came good old Sandy, who convinced Martin of the benefits of heavily insuring both the vessels and cargo — sound advice which he took, even allowing Sandy to make the arrangements on his behalf. True to form, Martin passed the papers into Sandy’s trust along with power of attorney in case of his untimely demise. The fat Haligonian then had another great idea for his gullible friend: Martin should sail one of the two schooners to Dixie himself! The fact that it was November, a particularly dangerous time to sail, replete with whiteouts and freezing gales, did not seem to register with Martin, though his family begged him to reconsider. His first vessel, the

Marie Victoria

, was shipwrecked near Bic before even leaving the St. Lawrence. Though the crew swam to safety, Booth’s theatrical costumes sank into its murky depths, much like his dreams of a Confederate state. Patrick Martin disappeared with his flagship, never to be seen again. Sandy received $100,000 in insurance payouts, and refused to give his colleague’s widow one red cent, plunging her into poverty.

With the American Civil War drawing to a close, Sandy took the opportunity to swindle as many of his Haligonian friends as he could, before sneaking across the border to eventually settle under the alias “A.K. Thompson” in New York City. He brought his lover Mary Clifton, a former chambermaid at the Halifax Hotel, with him, and the two enjoyed a life of luxury. However, Sandy was as blundering at legitimate business ventures as he was deft in illicit ones, and he soon lost $100,000 on the stock market. Having made enemies practically all over North America, he became a nervous wreck, obsessing over the notion that they would come seeking their revenge. New York City may have been colossal, but many of his foes had connections there. He told Mary that he was leaving for St. Louis, Missouri, and would soon send for her. Of course, that was the last she ever saw of him. After discovering she was pregnant, she was forced back to the role of lowly chambermaid in order to buy her passage back to Halifax. There she gave birth to Sandy’s twins, and later attempted to commit suicide.

A.K. Thompson, as Sandy Keith now liked to be known, stepped off the train in St. Louis in January of 1865, and booked a room in the Southern Hotel. He wasn’t long there before detectives and other men out for his head began showing up in the city. Sandy decided that unless he wanted a knife in his back, he would have to not only avoid the lavishness of city life, but relocate far away from the railroad. His solution was to move to the middle of nowhere, or more specifically Highland, Illinois: a bucolic community accessible only by coach, which harboured a large Swiss population. He arrived in the spring of 1865 and checked in for a long-term stay at the Highland House. Living off his immense wealth and enjoying what luxury he could in this remote location, Sandy began taking German lessons. While socializing one night in a beer garden, he was introduced to a dark French beauty by the name of Cecelia Paris. The twenty-year-old was a cultured milliner, fluent in several languages, with immaculate taste and manners. Though Sandy had always aspired to move seamlessly among the elite, he had never shed the crassness of his brewer’s roots, and saw Cecelia as his chance at a more refined existence. He won her spendthrift heart instantly, flashing $75,000 in bonds. The two courted briefly before marrying in the summer. Amazingly, their union seems to have been a happy one for a time. Sandy, who was in the habit of waking up terrified of assassins by his bed, reluctantly confided in Cecelia that he had been involved in blockade running. Yet everything else he told his new bride was either a lie or gross distortion. To our knowledge, she never learned his true identity.

Things took a turn for the worse in the days before Christmas, when the couple were awakened at night by an unexpected knocking on their door. Dressed only in his nightclothes, Sandy opened it to discover Luther Smoot along with a U.S. marshal with a warrant for his arrest. Smoot had finally tracked his old nemesis through Mary Clifton, from whom he had learned that Sandy had absconded to St. Louis. Without uttering a word of explanation to Cecelia, Sandy allowed himself to be taken to St. Louis, where he was imprisoned in the local jail. While in the city, Smoot tried to convince an unlikely friend, General William Tecumseh Sherman, to have federal troops intimidate Sandy into reimbursing him. Sherman replied that he could not oblige his friend. Frustrated, Smoot finally reached a grudging compromise with Keith: Sandy would give him $10,000 in bonds in return for his freedom. Sandy was loosed from his cage in 1866, and travelled with Smoot to the local bank, where he handed him the bonds. Before he left, Smoot sternly admonished Sandy to repay his creditors or there would be further trouble down the road. Specifically, he mentioned the name H.W. Kinsman, and warned Sandy that he would not cover for him.

When Sandy returned to the distraught Cecelia at Highland House ten days after his arrest, he was a nervous wreck. He informed her that he was being hunted by bad men, and that they had to leave for New York. On January 13, 1866, the “Thompsons” watched from the deck of the

Hermann

as the American coast grew smaller and smaller, until it was swallowed by the horizon. Sandy was about to put his German to good use.

The Darlings of Dresden

Twelve days later, the Thompsons landed in the Germanic port of Bremerhaven, and travelled by train to the historic city of Dresden in Saxony. Here, Sandy altered his alias to William King Thompson, and he and Cecelia adopted the guise of a southern gentleman and his New Orleanian belle. Through his dealings with Confederate bluebloods in Halifax, Sandy had learned to emulate their accents, style, and cultural airs surprisingly well, even compiling their personal stories into a fake biography for himself. With $45,000 — roughly $1 million in today’s currency — still in their possession, coupled with the romanticized image of the southern plantation owner, the well-to-do Thompsons mixed easily with European aristocrats and wealthy American ex-pats alike. They joined the exclusive American Club, where Sandy enjoyed all of the pleasantries he had become accustomed to over his life: brandy, cigars, euchre, and nepotism. He and Cecelia hosted teas and threw extravagant parties, cementing their high-society status in Dresden and the surrounding area. Things were going so well that in 1868 the couple started a family, producing Blanche, William, and Klina within four years. Given Sandy’s ineptitude in legitimate business, their extravagance would not last forever. Had either he or Cecelia opted to live more frugally, they might have enjoyed a comfortable life in Dresden until their deaths. Yet they chose opulence and admiration over common sense, and by the end of 1872, Sandy had a meagre $2,500 in his bank account. Defaulting to his criminal ways, he decided that the solution was to blow up a steamer to collect the insurance money. To do so, he would need a special kind of time bomb.

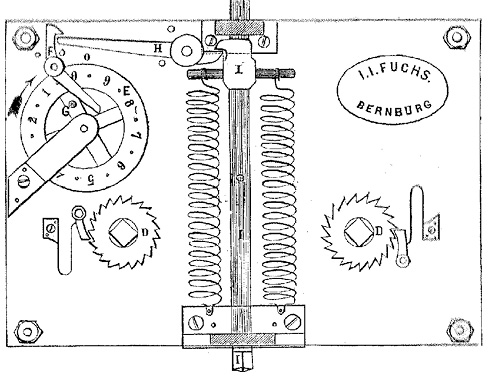

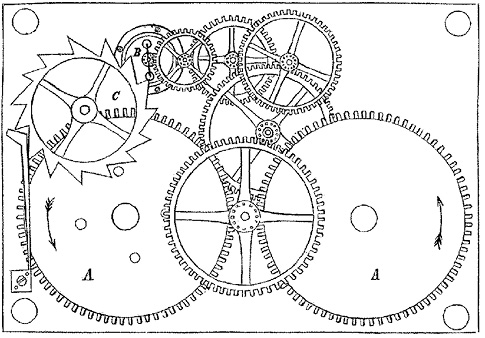

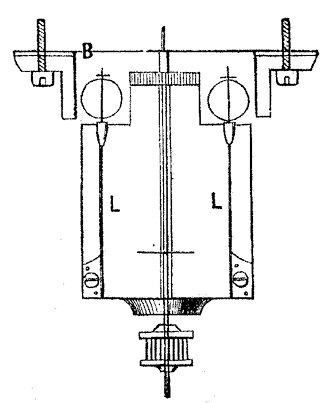

Sandy approached one of the finest clockwork engineers in Europe, J.J. Fuchs of Bernberg, to inquire whether it was possible to build a spring-loaded device capable of running silently for ten days before releasing a lever. Though Thompson would provide no details of his intended use for the mechanism, Fuchs nevertheless accepted the challenge. However, secretly he questioned Thompson’s seriousness and, as a result, put the project on the backburner, eventually forgetting about it. Meanwhile, Sandy and Cecelia had been forced to move into a new home, which they dubbed Villa Thomas — a dwelling so inferior to their previous one that they struggled to find servants to work for them. It was 1863, and the holdings in Sandy Keith’s bank account now stood at $1,600. He pleaded with Cecelia to rein in her spending, but she laughed at his attempts. One day, when he received an astronomical milliner’s bill, he flew into a rage and beat her. Cecelia took to bed, refusing to speak with him. Desperate, Sandy approached two Viennese clockworkers with his idea, but after several attempts to construct the mechanism they were unable to produce a lever that struck with the necessary force. Reluctantly, Sandy returned to Fuchs’s workshop with the thirty-pound Viennese prototype and informed the clockmaker that he required a similar, more forceful device that would release a lever after twelve days and stay intact even while in motion. Unaware that he was about to be an accomplice to the worst mass murder of the nineteenth century, Fuchs fashioned the mechanism to perfection.

Diagrams of Keith’s clockwork time bomb.

Diagrams of Keith’s clockwork time bomb.

Deutscher Hausschatz, 1876

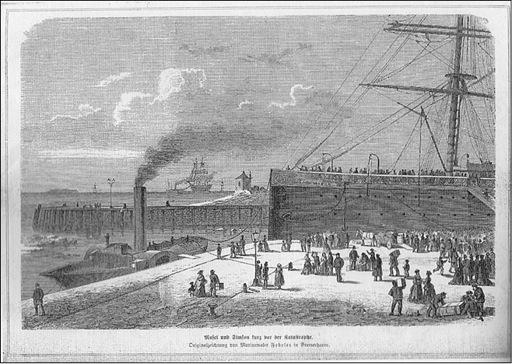

Soon after, Sandy Keith procured some dynamite, and headed to Bremerhaven. There he decided upon a target — the

Mosel —

scheduled to sail from Bremerhaven to Southampton, England, before continuing on to New York. Sandy booked passage on the vessel as W.K. Thomas, and attempted to insure twenty-seven chests to be loaded onboard, reneging after learning that the premium was too high. In the end, he settled for 3,000 marks (the equivalent of £150) for a barrel of caviar. His plan was to sail with the

Mosel

to Southampton, disembark, and return to Dresden, where he would await the news that the steamer had been lost at sea, and collect his insurance money. He had become so greedy and callous that he was now willing to sacrifice the lives of hundreds of people to gain a mere £150 and to see whether his “infernal machine” actually worked.

On December 11, he presented his passport and went to his first-class cabin on the

Mosel

. Less than an hour later, eighty-one people were dead, and Sandy attempted to join them by shooting himself. Unfortunately for Sandy Keith, he wouldn’t get off that easily.

Nineteenth-century illustration of the steamer Mosel in harbour, immediately before its explosion.

Nineteenth-century illustration of the steamer Mosel in harbour, immediately before its explosion.

Deutscher Hausschatz, 1876