R. A. Scotti (7 page)

Authors: Basilica: The Splendor,the Scandal: Building St. Peter's

Tags: #Europe, #Basilica Di San Pietro in Vaticano - History, #Buildings, #Art, #Religion, #Vatican City - Buildings; Structures; Etc, #Subjects & Themes, #General, #Renaissance, #Architecture, #Italy, #Christianity, #Religious, #Vatican City - History, #History

IMPERIAL DIMENSIONS

I

f a grain of sand can show us the world, then Bramante's Tempietto can show us his Basilica. Alberti defined architectural perfection as a geometric construction in which all elements are proportioned exactly. He called it

concinnitas:

“I shall define Beauty to be a harmony of all the parts, in whatever subject it appears, fitted together with such proportion and connection, that nothing could be added, diminished, or altered but for the worseâ¦.”

Begun around 1502 and celebrated ever since, the Tempietto exemplified that Renaissance ideal in microcosm. It is impossible to imagine the slightest modification. Just fifteen feet in diameter, it was commissioned by Spain's royal couple, Ferdinand and Isabella, a decade after they had sponsored another aging Italian's quixotic adventure.

Bramante's “little temple” turned the circular temple of antiquity into a Christian martyrium. Sebastiano Serlio, whose sixteenth-century book on architecture stands with the works of Vitruvius and Alberti, calls the Tempietto “a model of balance and harmony, without a superfluous detail. The circle of the ground plan, the height of the drum, and the radius of the dome are in exact ratio one to the other.”

The Tempietto and the Basilica are Bramante's foremost achievements. Both are dedicated to St. Peter, and they are the smallest and the grandest constructions in Rome.

Â

For many years, in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, in a small room with a view of the Arno, ochre colored and meandering, within the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe Architettura, inside an imposing armoire that appeared as old as the building, a cloth-covered box, eighteen by twenty-four inches or so, held an architectural study, labeled Uffizi No. 1A. It is one among scores of drawings, nine hundred in all, dating from the same few years, 1503â13, the papacy of Julius II. Most of the studies were executed for Bramante by his pupils and assistants.

Uffizi No. 1A is different from the others. The paper, though now too brittle to touch, was more expensive and of a higher quality than the typical drawing paper from the same period. It was folded over several times, and each crease is worn thin and cracked. When opened the plan measures more than three feet by twenty inches and is drawn on a scale of 1:150. In spite of its large size, it is only one half of a blueprint known as the Parchment Plan. The missing half was presumably a mirror image.

The study was drawn in brown ink, then traced over in watercolor. Though faded now, the wash is still a warm umber tone, a few shades softer than the roof tiles of Tuscany. On the back, scrawled in ink, is a note saying, “

di mano di Bramante, non ebbe effetto

,” in effect, a plan “by the hand of Bramante, never executed.”

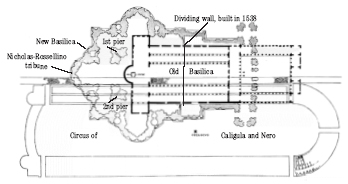

The Parchment Plan may be the very paper that Bramante presented to Pope Julius, and later showed to the workers when he was explaining his design for the new Basilica. Together with the commemorative medal coined for the foundation-stone ceremony, it gives the best visual clue to his original design. The one shows the interior, the other the exterior.

For the first church of Christendom, Bramante imagined the dome of the Pantheon raised on the shoulders of the Basilica of Maxentius, the last and largest basilica built by the Roman emperors. On the commemorative medal, the Basilica appears as a vast horizontal structure, with a hemispherical dome rising above a colonnaded drum, a bell tower on each end and four secondary towers.

Like the original St. Peter's, Bramante's design fused the Christian shrine to a martyr and saint with the pagan basilica. Placed directly over the apostle's grave, the martyrium was the essence of the new St. Peter's. It was also Bramante's boldest concept and greatest challenge. Like the Tempietto, his St. Peter's was a central planâround because the circle, without beginning or end, is the perfect symbol of God, and domed. An immense basilica extended from the central shrine.

Bramante's design was both true to the Renaissance ideal and a radical departure from it. He composed an exercise in geometry, made up of perfectly proportioned parts within parts. It was a symmetrical Greek cross with four arms of equal length. The interior was a series of identical shapes in ever-diminishing size. Within each arm were smaller crosses, and within their arms still smaller crosses forming chapels, each exactly half the size of the next largest. The four corner chapels were as big as most conventional churches. By making them replicas on a 1:2:4 ratio, Bramante drew attention to the enormous central space.

Although the Renaissance ideal was Greek in spirit, shape, and scale, Bramante's Basilica was Roman. He was inspired by two of the monuments that he had studied so closely, yet he departed dramatically from imperial architecture. Ancient Roman basilicas were rectangular roofed constructions, Roman temples were domed. By uniting these two distinct imperial formsâthe basilica and the templeâhe imagined a new Christian Basilica.

Bramante's first inspiration, the Basilica of Maxentius, also known as the Temple of Peace, opens onto the Forum and was reputedly the last, the largest, and the most magnificent basilica built in Rome. It was begun by Maxentius in

a.d.

308 and finished by his rival and challenger Constantine five years later, no mean feat considering its massive sizeâ115 feet high by 262.4 feet long. Like the typical Roman basilica, it was a rectilinear construction, but it rose to a distinctive three-dormered roof. Two stories of tall arched windows filled the interior with light. Within the basilica, marble colonnades divided the vast space into a high wide nave flanked by narrower aisles. The nave ended in an apse, which Constantine filled with a heroic-size statue of himself.

Bramante's second inspiration is an architectural wonder. The Pantheon is a large circular edifice, built as a pagan temple to the multiple gods of Rome and some time later rededicated to the Blessed Virgin. Each element of it astounds: the brilliant lighting achieved by a single eye in the skyâa 27-foot-wide oculus in the center of the dome; the solid walls 15 feet thick bearing the weight of the dome; and the massive dome itself. A marvel of construction and engineering, it is a 143-foot hemisphere, equal in diameter and height, constructed of cement faced with brick.

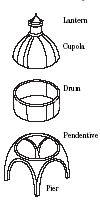

The parts of a dome.

Monumentality was a distinctly Roman conceit, and Bramante embraced it. His Basilica covered 28,700 square yardsâa third again (11,350 square yards) as large as St. Peter's is today. Like the Pantheon's dome, his was as smooth and shallow as a porcelain saucer. Yet there were radical differences. Ancient temple domes sprang directly from the circular outer wall.

Bramante's cupola rested on a drumâa ring of uniform columns, each one 60 feet in circumferenceâand was held aloft by four massive piers. Arched by coffered barrel vaults, it towered 300 feet in the air. Its width was almost twice that of the nave and its diameter of 142 feet was equal to the Pantheon's and just shy of the Duomo's in Florence. Like the dome of the Pantheon, it was planned as a single shell constructed of cemented masonry. Bramante carried through the same 1:2:4 ratio in the proportion of the crossing arches to the dome. Their height was twice their span, and the total height of the dome was four times the arch span. For the exterior, he imagined a crescendo of smaller domes of increasing size over the apses and corner chapels culminating in the immense central dome.

By the norms of Renaissance architecture, Bramante's Basilica was revolutionary. In its titanic scale, in its use of space as an architectural force, and in its shape (the divine circle inscribed within a square), Bramante abandoned the serenity that was Greece for the drama that was Rome. The new St. Peter's has been called the boldest experiment in religious architecture ever conceived. Nothing comparable had been attempted since the days of imperial Rome when Constantine raised the first basilica.

Â

The Roman architects were extraordinary engineers. But somewhere on the long, rutted road from antiquity to the Renaissance, the techniques they devised to erect massive arches and vault vast spaces were forgotten. Even the material that made their feats of engineering possible was lost. To build his church, Bramante had to rediscover their methods.

Building on such a scale and with techniques not attempted for more than a millennium made much of the construction trial and error.

Bramante coaxed the secrets of the ancient architects from the ruined city and welded Roman forms to Renaissance principles. The papal goldsmith and memoirist Benvenuto Cellini described his skill: “Bramante began the great church of St. Peter entirely in the beautiful manner of the ancients. He had the power to do so because he was an artist, and because he was able to see and to understand the beautiful buildings of antiquity that still remain to us, though they are in ruins.”

Centuries of architectural history and tradition came together in Bramante's planâthe arch, vault, and dome introduced by the elusive Etruscans; the harmonious proportion and unity of the Athenians; and the Romans' remarkable use of brick and concrete, which formed the structural basis for the domes, piers, and arches of their massive constructions.

Â

Concrete is one of those dull, unsung inventions that make extraordinary achievements possible. When the architects of the Caesars had the inspired notion to mix sand and volcanic gravel, they came up with a substance that was handy, plastic, and extremely durable. If they used bricks and poured concrete, they didn't need beams. They could support massive weights on piers alone and vault vast spaces, creating buildings on a heroic scale with immense open floors and soaring ceilings.

By the second century, Romans were building both infrastructures and architectural marvels with concrete masonry. They could produce it cheaply and easily by combining pozzuolana, a volcanic gravel, with lime, broken stones, bricks, and tufa, a porous deposit found in streams and riverbeds. The ingredients were mixed with a small amount of water and beaten vigorously. The small proportion of water allowed the cement to set quickly, and a thorough beating ensured a durable substance.

Roman concrete not only built the Pantheon, the baths, the aqueducts, and other engineering works, remnants of which still mark the landscape of Europe, it also paved all the roads that led to Rome.

To rediscover the brick-and-cement building skills of the emperors, Bramante studied the antiquities and consulted the Vitruvian text that Alberti had tried to interpret for Renaissance builders. As Alberti noted, Vitruvius was the only architectural writer to survive “that great shipwreck of antiquity,” and he was such a poor stylist “that the Latins thought he wrote Greek and the Greeks believed he spoke Latin.” From Vitruvius, Alberti drew attention to the giant pilasters, the colossal orders, and the massive barrel vaults that were essential elements in imperial architecture. Bramante would make them essential elements in the new Basilica, combining them in ways the Romans had never attempted.

In essence, barrel vaults are tunnels formed by a series of abutting arches. Because rigid concrete vaults exert no lateral thrust, the Romans could span expanses of vast height and width, creating a monumental architecture. For the concrete vaults in his new Basilica, Bramante had to train artisans in the “new” masonry and establish an on-site operation at St. Peter's to form, shape, and cut the bricks.

Writing some twenty years after Bramante's death, Serlio called him “a man of such gifts in architecture that, with the aid and authority given to him by the Pope, one may say that he revived true architecture, which had been buried from the ancients down to that time.”