R. A. Scotti (10 page)

Authors: Basilica: The Splendor,the Scandal: Building St. Peter's

Tags: #Europe, #Basilica Di San Pietro in Vaticano - History, #Buildings, #Art, #Religion, #Vatican City - Buildings; Structures; Etc, #Subjects & Themes, #General, #Renaissance, #Architecture, #Italy, #Christianity, #Religious, #Vatican City - History, #History

A CHRISTIAN IMPERIUM

T

he year 1507 was pivotal in the building of the new St. Peter's. By the time the papal calvacade rode into Rome to a triumphant welcome, the first pier of the new Basilica was rising behind Constantine's church. It was an astounding sight. The titanic northwest pier stood 90 feet high and was almost 30 feet thick, with a circumference of some 232 feet. Work was already under way on the corresponding southwest pier. Since neither impinged on the existing structure, the old basilica was still intact. By April, though, the inevitable could no longer be delayed.

Bramante began to raze the millennium-old church. In his enthusiasm, he ripped the roof off the Confessio, the main altar area, and tore down the walls, destroying priceless art, altars, votive chapels, and mosaics. His reckless bravado provoked widespread fury. Romans jeeringly named him “the wrecker,” and Paris de Grassis noted in his journal, “The name

il Ruinante

has been added to the vocabulary to describe Architect Bramante.”

Perhaps because his heedless demolition was raising such an outcry, Bramante adopted a novel approach. Instead of leveling the old church entirely and laying a new foundation, he worked in sections, building the new Basilica piece by piece and continuing to demolish the old one as needed.

Although the roof was gone, he preserved the main altar. Unfazed by either the construction going on around him or the weather, Julius continued to hold ceremonies there. As long as he was pontiff, he celebrated the papal mass al fresco to the distress and vexation of many of his cardinals. Paris de Grassis complained ceaselessly of the trouble he had organizing papal functions amid the scaffolding and boards in the

maledetta fabbrica

â“the accursed construction.”

Â

Destruction and construction became an ongoing process that would stretch over the course of the century. At the same time, Bramante continued to draft new plans. His methods were unorthodox. In his rush to build, he seemed to try out each new idea as it came to him. He began work while his own architectural plans were still jelling, returning to Julius repeatedly with revisions and changes.

The Basilica that was rising in 1507 was not the design that Julius had accepted originally. There is no way to know why Bramante went back to the drawing board, beyond the ferment of his endlessly fertile mind. Vasari wrote that he bombarded Julius with hundreds of designs. Although his sketches include both cruciformsâthe T-shaped Latin cross and the equi-armed Greek crossâBramante's preference was the central plan. It was a truer reflection of the Renaissance ideal and a truer spiritual metaphor.

The metaphysical core of the Basilica was Peter's grave, the “rock” of the Roman Church. In the Greek cross, it was located at the very center of the building. The dome rose over it, symbolizing the transcendent Christ, and the arms of the Basilica stretched out in equal length from it, representing the Church reaching to the four corners of the world.

The Basilica that Bramante probably adopted is a variation of the Parchment Plan. A sketch of the new design was drawn by one of his assistants, Domenico Antonio de Chiarellis, known as Menicantonio, a diminutive of the first and middle names. Only discovered in the 1950s and now in the Mellon Collection of the J. Pierpont Morgan Library in New York City, the Menicantonio Sketchbook is crudely made, with cardboard covers, the front one strengthened with a sheet of parchment, and measures roughly eight inches by seven inches. There are eighty-one folios on strong drawing paper, and the signatures and covers are bound with double strings.

In the Mellon Codex plan, the essence of Bramante's Greek cross remains “the dome of the Pantheon raised on the shoulders of the Basilica of Maxentius.” Only the details changed. Once again, Bramante began with the Renaissance ideal, and then went beyond itâestablishing an exact geometry before deviating from it. In that, he was truer to Vitruvius than architects who hewed more closely to the Renaissance conventions. Vitruvius never encouraged the slavish adherence to ratio and proportion that became the rule of the Renaissance. “The architect's skill must be brought in,” he wrote. “He will introduce those corrections into the general symmetry, increased in some places and reduced in others, which will make the building seem to have no fault.”

Although the “corrections” Bramante introduced seem small, they created striking architectural illusions. The towering height of the apses introduced a vertical drama that was lacking in the more horizontal church pictured on the commemorative medal.

While his massive dome was still set on discrete piers rather than on a solid cylindrical base, Bramante turned the piers on the diagonal. Instead of making four corners, the angled piers form an octagon. He turned the piers in the corner chapels on the diagonal as well. What may seem like a simple deviation had an exhilarating effect. By eliminating the ponderous square corners, he created a dynamic central crossing. Bramante, who has been famously criticized for cutting corners in his rush to build enormous structures in the shortest possible time, here cut them to brilliant effect.

Although the body of Bramante's Basilica seems to have changed many times, its essence remained the enormous central dome. His enthusiasm for it was so great that he began building St. Peter's from the center out. By the end of the year, the foundation stones of all four piers had been blessed and laid, and work was proceeding at a furious speed.

Julius visited the construction site often and showed it off to visiting dignitaries. One envoy wrote, “His Holiness shows every happiness and frequently goes to the building of St. Peter's demonstrating that he doesn't have any greater concern than finishing the building.”

Another reported, “The pope went today to visit the church of St. Peter and inspect the work. I was there also. The pope had Bramante with him, and he said to me smiling, âBramante tells me that 2,500 men are at work here. One might review them. It is an army!'”

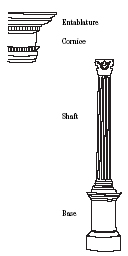

The parts of a column.

Bramante raised the ninety-foot piers and crowned them with Corinthian capitals, twelve palms high, or about six feet, carved with olive leaves. All the double pilasters and columns throughout St. Peter's repeat the same colossal Corinthian order. In an intense surge of construction that continued through 1510, he joined the piers with coffered barrel vaults that soar one hundred and fifty feet, higher than the dome of the Pantheon.

Bramante's heroic crossing arches established the height of the transept and nave,

*

as well as the diameter of the dome. His unorthodox strategyâbuilding from the center outâfixed the nucleus of St. Peter's immutably. By concentrating construction on the Basilica crossing, he ensured that the monumental scale could not be diminished no matter who succeeded him, and he kept his options open. Until the crossing was finished, he could continue experimenting with the shape of the surrounding Basilica.

Â

The cost of building the Basilica was commensurate with the astonishing progress. In the Middle Ages, construction of the Gothic cathedrals had been consigned to an independent organization. Often called a chapter or an opera, it handled all building issues, mediated disputes among the various craftsmen, paid the bills, secured the material, and generally took care of details, large and small.

But Julius didn't delegate. In spite of his impetuous rush to build and his scandalous disregard for history, he was a conscientious manager, and he signed off personally on every detailâaesthetic, practical, and financial. As long as he was pope, there was only one authority. While his accountant Girolamo de Francesco, his bankers Stefano Ghinucci and Agostino Chigi, and his cousin and cardinal-chamberlain Raffaele Riario advised him, the pope held the purse strings himself. Julius allocated funds from the Camera Apostolica and the Tesoreria Segreta, his personal expense accounts, and paid his architect directly. Bramante, in turn, paid his assistants out of his own pocket. Ghinucci disbursed payment to suppliers, laborers, and craftsmen.

Artisans were paid by the pieceâso many ducats for a square foot of flooring, wall, roofing, or pavement; so many for a cornice or capital. Each expenditure was noted in a

liber mandatorum.

Still filed in the archives of St. Peter's, this slim, eighty-page “book of commissions” is a concise record of the cost of the new Basilica and the pace of construction during Julius's pontificate.

In 1506, the first year of building, total expenses were 12,500 ducats. The papal ducat was comparable to the euro today. It was an international coinâthree and a half grams of pure gold. Although it is difficult to make an accurate comparison with today's dollar, in 1506 a laborer worked for 15 to 20 ducats a year, a teacher or clerk earned 25 to 30 ducats, and a skilled craftsman brought home on average about 50 ducats. On the other end of the social scale, lifestyles were so lush that a nobleman with an income of 1,000 ducats was just making ends meet. Two thousand ducats relieved financial headaches.

Depending on how you liked to spend your money, for 2,000 ducats you could buy twenty translations of Homer, hand-lettered; muster your own army for a couple of months; hire an artist to fresco your house; or buy your way into the Curia, the main governing body of the Church.

In 1507, building expenditures more than doubled from the first year, and Julius saw no end in sight. The new St. Peter's would be an enormous expense for the Church for years to come. Much as nonprofit institutions do today, he appealed to the conscience of wealthy donors, in effect launching a capital campaign to underwrite construction. In a papal bull, signed on February 13, 1507, he asked the crowned heads of Europe for donations.

“The New Basilica, which is to take the place of one teeming with venerable memories, will embody the greatness of the present and the future. In proportions and splendor we believe it will surpass all other Churches of the Universe,” he wrote.

Henry VII of England sent tin for the Basilica roof and was rewarded with wheels of Parmesan cheese, globes of provolone, and barrels of wine. In spite of the generous response, much more was needed. Operating costs were soaring, and in April, Julius imposed a tribute on all apostolic properties, with 10 percent of the revenue earmarked for the Basilica.

If the monies flowing into the Vatican treasury were enormous, so too were the outlays. The Church was a religious institution, a charitable and humanitarian enterprise, a civil authority, an educator, and a patron. It operated in many countries, had a large payroll, administered the city of Rome, maintained an army, ran numerous charities, social services, and universities, and funded the arts and sciences.

Total annual expenses were always substantial, but the pope's military campaigns, lavish patronage, and ambitious building projects made 1507 especially costly. Over time, the revenue returning from the Papal States, the increased income from the alum monopoly, and a lucrative new sourceâgold and silver from the New Worldâwould ensure the financial stability of the Church. But Julius faced an immediate cash-flow problem, and so his operating budget was strained.

With expenditures on the Basilica escalating from 12,500 ducats in 1506 to 27,200 in 1507 and facing years of building, he looked for a way to underwrite future construction, and he called on Agostino Chigi for advice. Among the many bankers who attended to the Church business, only Chigi was the pope's confidant and friend as well as his financier.

At a time when 2,000 ducats was a comfortable annual income for a noble, Chigi had paid 3,000 to purchase the coveted position of apostolic secretary, which assured him full access to Julius. Apostolic secretaries numbered only thirty and worked directly for the pope. Chigi continued to improve his portfolio, buying a position as notary of the Apostolic Chamber in 1507, and later, gilding his venal offices with the purchase of a noble title, court palatine.

The Apostolic Chamber was the finance department of the Curia. A classical Roman term referring to the Senate, the Curia of the early 1500s was small and informalâmuch different than it is today. Governance was divided among an administrative arm called the Apostolic Chancellery, a judiciary called the Rota, or wheel, and the Apostolic Chamber, the finance department, which was headed by a cardinal-chamberlain.

The pope's cousin Raffaele Riario served as cardinal-chamberlain. It was a position of substantial power. He hired the papal bankers, let out contracts, and oversaw a network of notaries, scribes, and clerks. Since Chigi's tax concessions and alum monopoly came under the jurisdiction of the Apostolic Chamber, becoming a notary was comparable to buying a seat on the board of directors of the corporation that owned your company. To Chigi, it was insurance. If the papacy changed hands, his leases would be renewed and his operations continue without interruption.