Pompeii (57 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

To this repertoire was added a priesthood of the reigning emperor, held by some of the most prominent citizens, including Marcus Holconius Rufus. The duties must have included sacrificing on important imperial occasions and anniversaries. But it is very likely too that holding the priesthood of the emperor was a fast-track way to getting noticed by the imperial hierarchy in the capital. Far below that level, even if they had many other functions in the town, the

Augus-tales

, as their name suggests, must also have had some responsibilities for the worship of the emperor.

New shrines or temples were built too. As well as the Temple of Fortuna Augusta, there was also a building on the east side of the Forum devoted specifically to the imperial cult. It is from this temple that the altar with its scene of sacrifice comes. And it is, in fact, the altar itself that gives away the connection with the emperor Augustus: the design on its back features two of the honours (the oak wreath and laurels) voted to Augustus by the senate in 29 BCE; and the face of the sacrificer bears more than a passing resemblance to that emperor. It was presumably here that the priests of the imperial cult would conduct their imperial sacrifices.

The overall impression, then, is that the emperor was becoming a bigger and bigger part of the religious world of Pompeii. But perhaps not

quite

such a large part as some modern scholars have claimed. It is predictable perhaps that the more interested archaeologists and historians have become in the Roman imperial cult, the more they have found its physical remains at every turn. Put simply, there is a tendency to find what you are looking for. In Pompeii, this enthusiasm has combined with the lack of much evidence about what several of the buildings on the east side of the Forum were actually for to encourage at least three buildings, or parts of buildings, to be assigned to the worship of the emperor.

In addition to the temple with the altar, there is the building next door, often labelled on no evidence at all ‘Imperial cult building’ (though the alternative idea that it was a library seems no better to me). Then, at the back of the

macellum

, there is supposed to have been another shrine to the emperor. This view is largely based on the discovery in the early nineteenth century of a marble arm, holding a globe (an imperial figure?) and a pair of statues which some have identified as members of the imperial family – though others (such is the difficulty of putting names to faces) have seen them as a couple of local grandees. As if that were not enough, some imaginative scholars have argued that the lump of concrete at the centre of the piazza was the base of a large altar dedicated to the emperor.

If all this were true, the Forum of Pompeii in 79 CE could only be described as a monument to dynastic and political loyalty, on a scale that would impress the most hard-line, one-party regimes of the modern world. Happily there is hardly a shred of evidence for any of it.

Mighty Isis

Were there Christians in Pompeii? By 79 it is not impossible. But there is no firm evidence for their presence, except for an example of a common Roman word game. This is one of those clever, but almost meaningless, phrases which read exactly the same backwards and forwards. It also turns out to be (almost) an anagram of PATER NOSTER (‘OUR FATHER’) written twice over, as well as two sets of the letters A and O (like the Christian ‘Alpha and Omega’). Some of the later examples of the same game do seem to have Christian connections. This one may too ... or it may not. The charcoal graffito which was said to include the word ‘Christiani’, but faded almost instantly, is almost certainly a figment of pious imagination. There is stronger evidence for the presence of Jews. No synagogue has been unearthed. But there is at least one inscription in Hebrew, a few possible references to the Jewish bible, including the famous reference to Sodom and Gomorrah (p. 25), and a sprinkling of possibly Jewish names – not to mention that kosher

garum

.

There were nonetheless other religious options for the people of Pompeii beyond the traditions we have already looked at. From as early as the second century BCE, there were religions in Italy which offered a very different kind of religious experience. These often involved initiation and the kind of personal emotional commitment that was not a crucial element in traditional religion. They often held out the promise to the initiates of life after death. This again was not an issue of great importance within the traditional structures of religion, where the dead did have some shadowy continuing existence and might receive offerings at their tombs by pious descendants – but it was certainly not a very desirable existence. These religions were commonly served by priests, or occasionally priestesses, who were more or less full-time, had a pastoral role with their followers and – unlike the

augures

and

pontifices

of Pompeii – lived a specially religious life. They might, for example, wear distinctive clothes or be shaven-headed. They often had an origin overseas, or at least defined themselves with recognisably foreign symbols.

It has proved very easy to misrepresent, and to glamorise, these religions. They were not direct precursors of Christianity. Nor did they arise in complete opposition to traditional religion, to provide the emotional and spiritual satisfaction that Jupiter, Apollo and so on did not. Nor were they practised predominantly by women, the poor, the slaves and other disadvantaged groups attracted by the promise of a blissful afterlife to make up for the wretched conditions of the here and now. They were very much part of Roman polytheism, not outside it, even if they had a shifting and sometimes awkward relationship with the authorities of the Roman state. So, for example, the worship of Bacchus (or Dionysos) and the Eastern goddess Cybele (also called the ‘Great Mother’) had both a civic and a more mystical version. The mystical, initiatory cult of Bacchus was severely restricted by the Roman authorities in 186 BCE, not far short of a total ban. Priests of the Egyptian goddess Isis were on several occasions expelled from Rome, but later Isiac religion received official sponsorship from Roman emperors.

109. Bronze hands, like this one found in Pompeii, are commonly associated with the Eastern god Sabazius. Its meaning and use is uncertain, but it is decorated with symbols of the cult (for example, the pine cone at the end of the thumb). One idea is that these hands were displayed on poles and perhaps carried in procession.

Several of these religions were known, even if not fully organised, at Pompeii. We have already looked at the frescoes in the Villa of the Mysteries which, though baffling and impossible to decode completely, certainly evoke some aspects of the cult of Bacchus, with its revelation of secret objects, and the sense of an ordeal that the initiate must undergo. One house not far from the Amphitheatre turned up various objects connected with the cult of the Eastern deity Sabazius (Ill. 109) – though whether the house was a fully fledged shrine of the god, as is often claimed, is a moot point. But by far the most prominent of these religions at Pompeii was the worship of Isis and other Egyptian deities.

Isis came in many guises, from protector of sailors to the mother of the gods. But one crucial element in her myth was her resurrection of her husband Osiris, who had been killed and dismembered by his brother Seth. Isis put his body together again and even went on to become pregnant by him with their child Horus. Hers was a story and a cult that offered hope of life after death. Something of the flavour of the religion for Roman worshippers is captured in the second-century CE novel by Apuleius,

The Golden Ass

. In this, after a series of terrifying adventures, the narrator Lucius is finally initiated into the Isiac cult. He describes the beginning of this process: the ritual washing, the abstinence (no meat or wine), the presents given by other worshippers, the dressing up in new linen. But of course he does not reveal the ultimate secret: ‘You may perhaps, attentive reader, ask anxiously what was then said and done. I would tell you if I could; you would find out if you could be told. But your ears and my tongue would be equally punished for such rash curiosity.’ But he does go on to make it clear enough that what was promised by the religion was the conquest of death: ‘Having reached the boundary of death ... I was borne through all the elements and returned.’

Figure 21

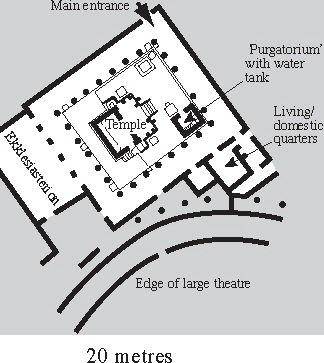

. Temple of Isis. Unlike the traditional civic cults of Pompeii, the Temple of Isis included room for a community of worshippers, and probably domestic quarters for the priests.

The Temple of Isis at Pompeii is one of the best-preserved, and least looted, buildings in the town (Fig. 21). Tucked into a small site right next to the Large Theatre, which looms above it, it had been recently completely rebuilt and was in full working order in 79 CE. It was hidden from the street by a high curtain wall, broken by a single main entrance up two steps and with a large wooden door. Enough survived of this for the eighteenth-century excavators to see that this door was made in three pieces. Just the central section would have given day-to-day access. It would, presumably, have been thrown wide open on festival occasions.

The door opened into a colonnaded courtyard (Ill. 110). In the centre stood a small temple, with other structures round about and further rooms off the courtyard. The temple was constructed of brick and stone, its outside stuccoed and painted. The walls of the courtyard itself were covered in frescoes. Hardly a spot was left undecorated. Statues were placed around the courtyard and in niches on the temple building itself. We quickly meet here again the old problem of labelling and reconstruction. Archaeologists have examined these remains for centuries, trying to match them up to descriptions given by ancient writers of the rituals and organisation of the cult of Isis, and to name the various parts. So, for example, the large room to the west is usually called by the Greek name

ekklesi-asterion

(‘assembly room’), and assumed to be the place where the initiates met. It may have been. But the important thing is to see how this complex differs from the traditional civic temples of the town, and how the different decorations and finds in the different areas may point to different functions.

The first thing to emphasise is that it was not open to public view, and the entrance was not welcoming to all-comers. This was religion for initiates. Secondly the building was catering for more congregational religious use and possibly a resident priest or two. Whether or not the assembly room really was for meetings of the members of the cult, there were places here for people to congregate and do things together. There were also a large dining room and a kitchen, and spaces that could be used for sleeping. As we have seen in other places, lighting was an issue. Fifty-eight terracotta lamps were found in one of the back storerooms.

The precise function of some parts is clear enough. The temple itself originally contained the cult statues of Isis and Osiris. These were not found in place on their podium inside. But an elegant marble head, found in the so-called

ekkle-siasterion

near some other marble extremities (a left hand, a right hand and arm, the front of two feet), may well be the remains of the acrolithic cult statue from the temple. The temple’s altar is outside in the courtyard, and opposite it is a small square structure, marking out a sunken pool. Whether or not archaeologists are right to give this the title

purgatorium

, it does very likely relate to the stress on washing and cleansing we find in ancient discussions of Isiac rituals. And not just any water would do. In theory at least the initiates of Isis bathed themselves in water brought specially from the Nile.

Meanwhile, whatever happened there, the decoration of the

ekklesiasterion

and that of the room next door marked them both as different from the rest. There were a few specifically Egyptian religious scenes in the decoration of the courtyard, but much of it seems to have had no particular relevance to the temple’s cult or Isiac myth. By contrast, in both these rooms the flavour is decidedly Egyptian. The ‘assembly room’ originally included at least two large mythological panels. One was a perfect emblem to greet new initiates: it depicts the Greek heroine Io, in flight from the goddess Hera, being welcomed to Egypt by Isis herself (Plate 18). The other room displays paintings of Isiac symbols, of the goddess herself and her rituals. In addition to the fifty-eight lamps, it was full of various pieces of religious equipment and Egyptian memorabilia, from a little sphinx to an iron tripod.