Pompeii (24 page)

Authors: Mary Beard

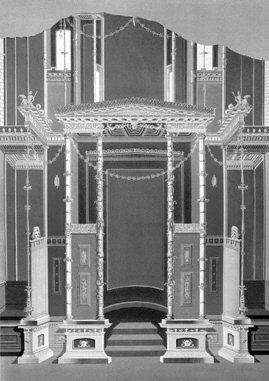

45. The walls of Pompeian houses often used painted columns, pediments and dadoes to create a vision of fantastical architecture. The effect of these two paintings is very different, but the standard division of the painting into three zones is clear in both.

Nonetheless, the imagination of the Pompeian painter and his patron was much more fertile than this. Looking around Pompeian houses, you would have spotted on their walls a range of subjects, themes and styles far wider than that modern stereotype suggests. Delicate landscapes were tucked away among the architectural fantasies, as well as touching portraits (Ill. 46) and still-lifes, not to mention stunted dwarfs, scenes of sex and fearsome wild beasts, both in miniature and on a grand scale. There were also styles of decoration much more like modern wallpaper than you would ever have predicted. Many householders painted long tracts of their corridors and service quarters with a black and white design, known for obvious reasons as ‘zebra stripe’, which would not have looked wholly out of place in the 1960s. Even a prestige room might be decorated in swathes of repeating geometric and floral patterns utterly unlike what we would think of as ‘Pompeian’ (Ill. 47). And all this variety was before you looked down at the floor, where, in the wealthier houses at least, almost anything that might be painted on the wall could also be turned into an image in mosaic, from guard dogs to the occasional full-scale battle. The ‘home decorating’ of Pompeii springs all kinds of surprises.

46. A striking image of a young woman with a stylus pressed against her lips, a detail less than 10 centimetres tall in the original. Modern imaginations have fancied – for no good reason – that she might be a portrait of the Greek poetess Sappho.

Particularly memorable are the large paintings that often plaster the whole back walls of garden areas. We saw the traces of painted foliage and other garden features on the wall of the House of the Tragic Poet, merging the real and imaginary garden. Other houses opted for something more exotic. Visitors to one relatively modest property (known as the House of Orpheus) would have been able to see straight through its front door to the peristyle garden at the rear – and to a well-over life-size figure of a naked Orpheus painted on the wall, sitting on a rock in a country landscape and strumming his lyre to the delight of a motley collection of beasts (Plate 2). On another garden wall, a colossal Venus emerges from the sea, sprawled out somewhat uncomfortably in her shell (Ill. 97). On another, a fantastic landscape, with palm trees in the foreground and grand villas in the distance, is the setting for a (painted) shrine of a trio of Egyptian deities, Isis, Sarapis and the child Harpocrates, the symbol of the rising sun.

47. Some of the wall decoration of Pompeii looks surprisingly modern. This patterned design from the House of the Gilded Cupids, believed to imitate fabric hangings, could almost pass for wallpaper.

Hunting scenes were also favourites (Plate 19). Even the small garden of the House of Ceii (named after its possible owners) offered visitors the thrill of the chase. The back wall of this space, not much more than 6 by 5 metres, is dominated by a dramatic hunt, with lions, tigers and other varieties of more or less fierce creatures (Ill. 48). But then turn to left or right, and the side walls are covered with images of the Nile and its inhabitants – pygmies hunting a hippo, sphinxes, shrines, shepherds muffled in cloaks, palm trees, sailing boats and barges (one loaded with

amphorae

). It is slightly clumsy workmanship. But the idea presumably was that to enter this tiny space should be to enter another world, part wild-animal park, part exotic foreign territory.

A whole variety of other themes was on display in sometimes elaborate painted friezes – and in sometimes surprising locations. We have already explored the surviving sections of the frieze from the Estate of Julia Felix, with its images of Forum life. But this was only one among many. All around the entrance hall of the private suite of baths in the House of the Menander ran a series of caricatures of the exploits of gods and heroes, humorous parodies of famous myths: Theseus, in the guise of a barrel-chested dwarf, killing the minotaur; a middle-aged and none too lovely Venus busy telling little Cupid where to fire his arrow (Ill. 51). In the same house, painting spilled onto the cramped surface of the low wall which ran between the columns of the peristyle: here herons pranced among some luscious plants, while a motley collection of wild animals were on the chase, hound after deer, boar sniffing after a lion.

48. The garden wall of the House of the Ceii, covered with an animal hunt. The painting is crude and patchy in its survival. But it still vividly brings the wild countryside into the tiny urban garden.

In a much more modest property close to the Forum on the Via dell’Abbondanza, now called the House of the Doctor (after some medical instruments found there), the wall between the columns of the small peristyle was covered with a frieze of pygmies. These were pictured getting up to all kinds of adventures, and into all kinds of scrapes: some attempting to catch a crocodile (Plate 22), one being eaten by a hippopotamus (while a friend vainly tries to pull him out of the creature’s mouth), a couple having sex in front of an admiring throng of pygmy revellers. But the most striking image is the scene which appears to depict a pygmy parody of the Judgement of Solomon, or some story on very much the same lines. Here a soldier is already wielding a large hatchet above the disputed baby, ready to cut it in half, while one of the claimant women, presumably its true mother, is pleading with three officials watching the scene from their raised dais (Ill. 49). If pygmies are not an unusual presence in various decorative schemes in the town (they have been found, for example, painted on the sides of the stone couches in one lavish outdoor

triclinium

, as well as in the House of the Ceii), the scene with the baby has no parallel elsewhere in Pompeii.

49. In this painting pygmies play out the story of the Judgement of Solomon (or some very similar tale). The disputed baby lies on the table, ready to be cut in two. On the right, one of its competing ‘mothers’ pleads in front of a group of judges seated on a raised dais.

Even so, for visual impact and intriguing subject matter, pride of place among friezes must go to the even more extraordinary series of paintings found in the Villa of the Mysteries (part working farm, part lavish domestic property), just over 400 metres outside the Herculaneum Gate. These now rival the Vettii’s Priapus as the iconic symbol of Pompeian art. They are reproduced on the same range of modern souvenirs, from ashtrays to fridge magnets – and have the added advantage that you don’t have to be quite so careful about who you give them to.

Life-size figures, set against a rich red background, running around all four walls of a large room, almost enclosing the viewer in the painting, they are a stunning example of ‘saturation viewing’ (Ill. 50). At one end, the god Dionysus lounges in the lap of Ariadne, whom he rescued after she had been abandoned by the hero Theseus – itself a favourite theme of Pompeian painting. Around the other walls, we are faced with a curious array of humans, gods and animals: a naked boy reading from a papyrus roll (Plate 14); a woman bringing in a loaded tray turns to catch our eye; an elderly satyr plays a lyre; a female version of the god Pan (a ‘Panisca’) suckles a goat; a winged ‘demon’ whips a naked girl; another naked woman dances to castanets; a woman has her hair braided, while a winged Cupid holds up the mirror. And that is to pick out only about half of what is going on.

To be honest, this is all completely baffling, and no amount of modern scholarship has ever managed to unravel the meaning – or, at least, not wholly convincingly. Some have argued that the images refer specifically to initiation into the religious cult of Dionysus. Note, for example, the flagellation, and the revelation of what might be a phallus on the end wall next to the divine couple. If so, then the room itself might have been some kind of sacred precinct within the house. This is not impossible, but it is certainly in no sense hidden away, as you might expect an esoteric cult room to be. In fact, it opens onto a shady portico, with a lovely view of the sea beyond; while on another side it has a large window looking onto the mountains in the distance. Others have seen the paintings as a rather extravagant allegory on marriage, and the young woman admiring herself in Cupid’s mirror as the bride. In which case, we are dealing with nothing specifically religious – but a perfectly plausible, if somewhat idiosyncratic, set of decorations for a major entertaining room. The house has been called the Villa of the

Mysteries

, after the Dionysiac ‘mysteries’ of initiation, following the strictly religious reading of the frieze. The truth is that these paintings are

mysterious

in the popular modern sense of the word too.