Pol Pot (54 page)

Authors: Philip Short

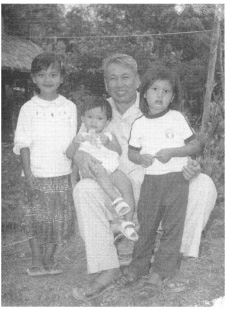

But few of his colleagues lived to see his new-found domesticity.

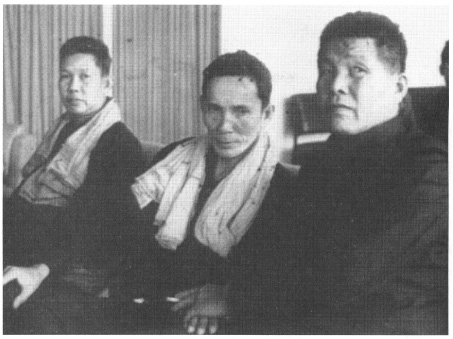

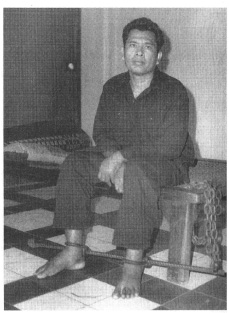

(From left to right, top)

Vorn Vet, Siet Chhê and Ney Sarann, and

(bottom right)

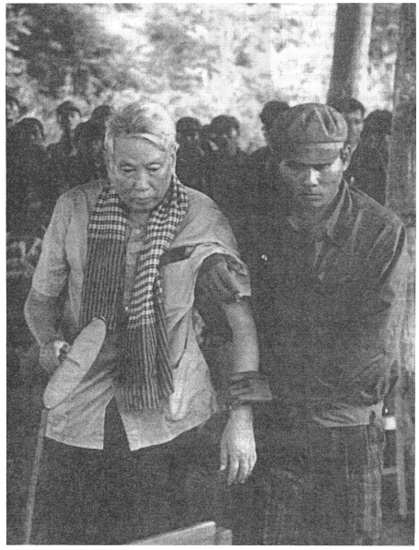

Koy Thuon, were all killed on his orders at the Tuol Sleng interrogation centre in 1977 and 1978. So Phim

(bottom left,

with Pol) committed suicide rather than face arrest.

(From left to right, top)

Vorn Vet, Siet Chhê and Ney Sarann, and

(bottom right)

Koy Thuon, were all killed on his orders at the Tuol Sleng interrogation centre in 1977 and 1978. So Phim

(bottom left,

with Pol) committed suicide rather than face arrest.

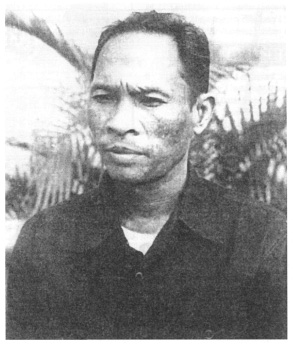

Left:

Heng Samrin, installed Vietnam as Cambodian Hea of State in 1979.

Heng Samrin, installed Vietnam as Cambodian Hea of State in 1979.

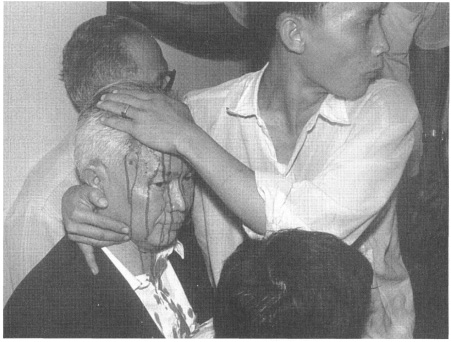

Right:

Khieu Samphân, beat by a mob sent by Hun Sen’s government, after his return Phnom Penh in November 1991 to implement the Paris peace accords.

Khieu Samphân, beat by a mob sent by Hun Sen’s government, after his return Phnom Penh in November 1991 to implement the Paris peace accords.

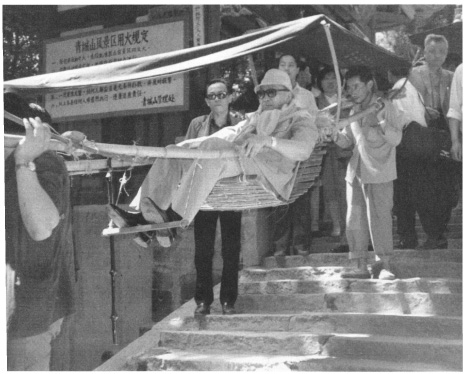

Below:

Pol Pot, being carriec mountain chair during a visit Mao’s old guerrilla base at Jinggangshan, in southern CI in 1988, and

(facing),

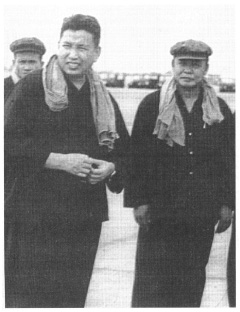

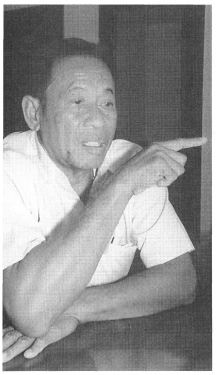

his two principal military supporters. Ke Pauk

(left)

and Mok.

Pol Pot, being carriec mountain chair during a visit Mao’s old guerrilla base at Jinggangshan, in southern CI in 1988, and

(facing),

his two principal military supporters. Ke Pauk

(left)

and Mok.

In July 1997 Pol Pot was brought before a mass meeting near Anlong Veng and sentenced to ‘life imprisonment’. He died peacefully in his sleep nine months later.

Yet it could have been far, far worse; After a five-year civil war in which half a million people had died and both sides were guilty of widespread atrocities, the fall of Phnom Penh was not marked by rivers of blood. At the Hotel Monorom, a few blocks south of the railway station, where the deputy front commander, Koy Thuon, established his headquarters, a ‘Committee for Wiping Out Enemies’ was set up. Its first action was to approve the execution of Prime Minister Long Boret, Lon Non, and other senior republicans, who were taken out and killed in the grounds of the Cercle Sportif, not far from the Information Ministry where they had been detained. Altogether, in the following days, seven or eight hundred politicians, high-ranking officials, police and army officers were killed and thrown into common graves on the road to the airport. So much for Sihanouk’s assurance that only the named ‘arch-traitors’ would be punished. But at least, in these early stages, there was no large-scale violence against the population as a whole. It would have been superfluous: people were so relieved that the war was over, they would have done anything the new authorities demanded. Most government troops simply abandoned their weapons and uniforms and fled. There were some exemplary killings, of long-haired youths, civilian looters who were caught pillaging shops or the occasional man or woman rash enough to defy a direct order, but usually a soldier had only to loose off a few rounds into the air to secure instant compliance. Of the eight hundred or so foreigners who gathered in the French Embassy, some had been put in great fear for their lives; yet none was wounded, let alone killed.

Early in the afternoon, the next phase began. Soldiers went from house to house, telling the inhabitants that they must leave ‘just for two or three days’, on the pretext that the Americans planned to bomb the city. Officers with loud hailers repeated the order.

The idea was not, in itself, far-fetched. Provincial towns overrun by the Khmers Rouges had often been bombed afterwards by government aircraft. The Viet Cong had used a similar subterfuge, likewise asking people to ‘leave for three days’, when they evacuated Hue during the Tet offensive in 1968. In both cases, the assurance that they would soon return disarmed potential resistance and, in theory at least, reduced the quantities of personal possessions the evacuees carried with them — which to Pol was important, since one unstated aim of the exodus was to strip bourgeois families of their worldly goods as a step towards reforging them in the mould of the poor peasantry amongst whom they were now to live.

Other books

Blank by Simone, Lippe

Pup by S.J.D. Peterson

Afloat by Jennifer McCartney

Hades by Candice Fox

Thirty Days: Part One by Belle Brooks

The Visitor by Brent Ayscough

Hemlock Veils by Davenport, Jennie

Half World by Hiromi Goto

Saving Her Destiny by Candice Gilmer

Kingsholt by Susan Holliday