Poison (40 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Eventually one of the women went to check on him. Leitch later heard the story and chuckled. “I guess they’d seen his Redd Foxx routine before, eh?” Piara was taken to hospital and released the next morning with a clean bill of health. He joined the other seven family members in custody. They were all shortly released on bail on condition they appear in court when required. The Khela affair meant they would be available as witnesses, but the controversy and delay prompted Bentham and Leitch to change strategy. They would try Parvesh’s murder first.

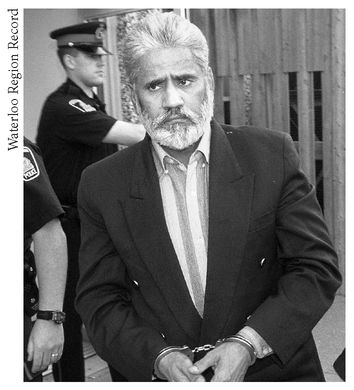

The trial began on May 16 in Kitchener. Sukhwinder Dhillon was led into the courtroom, the clacking of metal shackles announcing his arrival, and was seated in the prisoner’s box. Through the twin doors of Courtroom 1, the eight rows of pews for spectators were arranged as in an amphitheater, the wood trim dark brown like the inside of a church. Ten tall windows allowed in light on the left of the room. There was a cubicle for the accused, a table for the lawyers, and, off to the right, the jury box. At the front of the room, raised high above it all, was the judge’s bench with Ontario’s coat of arms on the wall behind.

Sukhwinder Dhillon being led into court in Kitchener, Ontario

Lawyers for both prosecution and defense were dressed in the traditional black robes with white collars. On the left side, Russell Silverstein with Apple Newton-Smith beside him. To their right Brent Bentham, the lead Crown, eyes buried in his papers. Beside him, big Tony Leitch leaned back in his chair, smiling pleasantly. Front pew, right-hand side of the courtroom sat Warren Korol and Kevin Dhinsa in custom-made suits Kundu had sent them from India. A bailiff stood and commanded those present to rise as Judge Glithero entered the room. “Her Majesty the Queen versus Sukhwinder Singh Dhillon. His Honor Justice C. Stephen Glithero presiding. You may be seated.” The jury filed in to take their seats.

“

Gal iddan hey, eh case paiey pickey khoon daa hey.

”

Gal iddan hey, eh case paiey pickey khoon daa hey.

”

The voice of Neeta Johar, the Punjabi court interpreter, could be heard faintly coming from the direction of Dhillon’s seat. She translated Bentham’s blunt opening statement to the jury: “This is a case about murder for money.”

The Crown began calling its long list of witnesses to give their testimony. Silverstein cross-examined each in turn. When the Crown was finished he could present his own evidence, if he chose. But that would carry a price. Under Canadian law, the defense gets the last word, addresses the jury last, only if it calls no witnesses. If it does call witnesses, the Crown speaks last. Silverstein decided to call witnesses, but the vast majority of the 92 people to testify at this trial were called by the Crown.

The first witness called by Bentham was a Hamilton woman named Parminder Bassi. She had known Parvesh back in Ludhiana, and had worked with her at the Narroflex factory in Stoney Creek. Inconsistencies in testimony emerged immediately. Bassi told Bentham that Dhillon himself had told her he gave Parvesh a painkiller pill the day she died. Silverstein pounced in his cross-examination. She had never made that claim before, not to Korol and Dhinsa when they interviewed her, or in court previously.

“I’m going to suggest to you today that this morning is the first time you have ever said that Sukhwinder told you that he gave this medication to Parvesh to take.”

“Yes,” she replied. “But he did tell me that he is the one who gave it to her. Today I am telling you—under no pressure—that this is what he said and this is the truth.”

Bassi’s change in testimony helped the Crown’s case, but other witnesses who changed their tune did not. Parvesh’s two daughters offered contradictory accounts of their mother’s death. The youngest, Aman, took her place in the witness box, her hair in a pony tail, wearing wire-rimmed glasses. She had been six and in Grade 1 when she watched her mother collapse. At the preliminary hearing, Aman had testified that her mother shook on the floor. And now one of Bentham’s key witnesses changed her story.

“Aman, did any parts of your mom’s body move when she lay on the floor?” Bentham asked. Dhillon, in his box, appeared to wipe a tear from his eye.

“I don’t recall,” Aman said. “I’m not sure. She looked normal. Like she was sleeping.”

Leitch hurriedly dug out Aman’s prelim testimony from the stack of papers on the desk and handed it to Bentham, who showed it to the girl.

“Please read this section very carefully,” he said. “Does this help refresh your memory about your mother’s appearance following her collapse?”

“No. My memory is better today, and now that I think about it, I can’t remember her moving.”

Aman left the witness box and walked past Dhillon’s seat. She did not look at her father. It wasn’t the last time in the trial a witness would go south on the Crown. On five occasions, Bentham would have to invoke Section 9 (1) and (2) of the Canada Evidence Act, asking Glithero to allow him latitude to cross-examine his own witnesses over inconsistent statements. It happened again on May 31. Bentham called a woman who had been one of several people who rushed to the Dhillon house when hearing of Parvesh’s collapse. But the woman no longer recalled the vivid descriptions of Parvesh’s condition she had offered in past statements in court. Bentham accused her of changing her story.

“How can I lie?” the witness countered through the interpreter. “She was like a daughter to me. How could I speak against her?”

The woman blamed Kevin Dhinsa for misinterpreting what she had told police—even though she herself had repeated her account in court at the preliminary hearing. The parade of Crown witnesses continued, neighbors, paramedics, physicians at Hamilton General Hospital, forensic pathologist Dr. David King, Parvesh’s family doctor Khalid Khan, insurance investigator Cliff Elliot, strychnine expert Dr. Michael McGuigan. Korol and Dhinsa testified on how easily they had purchased strychnine in India and walked it past airport officials in Toronto.

Silverstein cross-examined each witness. On the strychnine evidence, his primary argument was that if indeed strychnine was found in Parvesh Dhillon’s tissue samples long after her death, it wasn’t put there by her husband—it was contamination from testing at either the hospital or the Centre of Forensic Sciences. Or, if not contamination after her death, then Parvesh had consumed the poison herself, by accident.

Tony Leitch handled the forensic evidence part of the Crown’s case. He called six laboratory technicians from Hamilton General Hospital to prove contamination of Parvesh’s tissue samples was not possible. He asked technician Nancy Kunkel: “To your knowledge, is there any strychnine used in your laboratory?”

“None at all,” she replied.

Silverstein asked a CFS official if the tissue sample could have been contaminated by strychnine in his lab. Dr. Joel Mayer said no, not directly, and that cross-contamination of the samples by airborne particles was highly unlikely. He said evidence in the Dhillon case had been kept together but that the strychnine powder the police had brought from India was kept separate from the wax blocks of Parvesh’s tissue. Silverstein pointed out that some of the strychnine had been in a simple bag, not an air-tight container.

Silverstein said that Parvesh may have taken a strychnine product for therapeutic reasons—diluted versions of the product were available as homeopathic remedies popular in the East Indian community. Mayer acknowledged they could not be sure how much strychnine Parvesh ingested before her death.

“So she could have had a therapeutic level in her system?” Silverstein asked.

“Yes,” Mayer replied. “There’s no way to tell.”

CHAPTER 22

WONDERFULLY DEFIANT

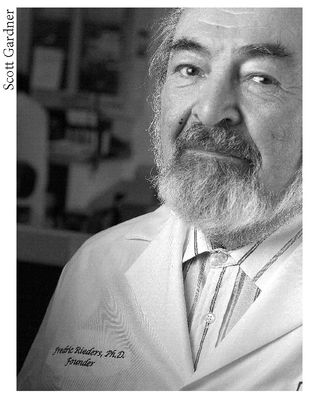

On Wednesday, June 20, a key Crown witness took the stand. It was Dr. Fredric Rieders. His resumé was impeccable. He was now 79 years old, silver-haired and with his style and his Austrian accent, he oozed

gravitas

in court. Warren Korol grinned as he studied the faces of the jurors. Rieders talking about toxicology was like having Moses up there giving his opinions on religion. His flair for explaining complicated scientific processes in ways the jurors could immediately understand made him the perfect expert witness. How would the doctor characterize the volume of strychnine found in Parvesh Dhillon?

gravitas

in court. Warren Korol grinned as he studied the faces of the jurors. Rieders talking about toxicology was like having Moses up there giving his opinions on religion. His flair for explaining complicated scientific processes in ways the jurors could immediately understand made him the perfect expert witness. How would the doctor characterize the volume of strychnine found in Parvesh Dhillon?

“The tissue contained a heck of a lot of strychnine,” Rieders said. Dhillon listened as the phrase was translated into Punjabi

. Ohdey tissue vichin kafi kuchila nikli hey.

Russell Silverstein would need all his skill to rattle Rieders. He took his shots.

. Ohdey tissue vichin kafi kuchila nikli hey.

Russell Silverstein would need all his skill to rattle Rieders. He took his shots.

“What, exactly, does ‘a heck of a lot’ mean?” Silverstein asked.

“It means it’s scientifically significant. She would have had to ingest quite a few milligrams for the count to be as high as it was.”

Silverstein proffered a medical counter theory to the doctor. If, he said, Parvesh was using small doses of strychnine for therapeutic purposes, is it not possible that when she fell into a coma, the body stopped breaking down toxins—and that could account for the strychnine levels in her tissues?

Possible, said Rieders. But unlikely. Coma patients tend to excrete a lot of urine which greatly helps to eliminate poison from the body.

Rieders sized up Silverstein. He is well-informed, the toxicologist thought. Intense, but not overbearing. Rieders had appeared many times as an expert witness in U.S. courts. Silverstein was more civil in his questioning than the lawyers he was accustomed to facing. Rieders knew well the American lawyer’s motto: if the facts are on your side, pound the facts; if the law is on your side, pound the law; if neither is on your side, pound the witness. Rieders had experienced the pounding first-hand over the years, the personal attacks, a hostile lawyer cornering him on the stand: “Doctor Rieders,

let me ask you once again, did you in fact spike that sample?” It got pretty raw sometimes, but then the toxicologist and lawyer who had battled in the courtroom went out for lunch together.

let me ask you once again, did you in fact spike that sample?” It got pretty raw sometimes, but then the toxicologist and lawyer who had battled in the courtroom went out for lunch together.

Dr. Fredric Rieders took the stand.

What else could Silverstein have done with the Crown’s star witness? He had heard something about Rieders running into difficulty over a lab calculation in a case in the U.S. not long before the Dhillon trial, but did not know the details. The problem had resulted in Rieders being dropped as a witness in that case. Silverstein knew that none of that mattered here, however. Rieders’s finding had been confirmed by a lab in Montreal.

Korol sat in one of the pews, laptop computer on his knees for taking notes. As Rieders stepped down from the stand and exited the courtroom, Korol leaned over. “Hey, thanks for coming, Dr. Rieders,” Korol said quietly. “Take care.” The toxicologist left the courtroom and headed back to Pennsylvania, to his lab, where samples of Parvesh Dhillon’s tissue remained in storage.

Other books

Tony Dunbar - Tubby Dubonnet 00.5 - Envision This by Tony Dunbar

The Detective and the Woman by Amy Thomas

Digging to America by Anne Tyler

6th Horseman, Extremist Edge Series: Part 1 by Anderson Atlas

The Ascension by Kailin Gow

Night Mare by Dandi Daley Mackall

The Promise of Lace by Lilith Duvalier

The Texan's Bride by Linda Warren

A Sister's Promise by Anne Bennett

The Burglar Who Liked to Quote Kipling by Block, Lawrence