Poison (11 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

On a cold Monday, January 30, Dhillon and Parvesh bought groceries at Centre Mall on Barton Street. Back at the house late that afternoon, with an unsold car sitting in the driveway, Dhillon lay on the couch watching TV while Parvesh, her head throbbing from another migraine, started to prepare dinner. Dhillon got up and brought her a capsule. Within minutes Parvesh collapsed, her body strangled by spasms and convulsions.

Life insurance money. That was the ultimate deal.

The summer of 1995 in Hamilton was hot and dry, farmers’ fields hard and arid, lakes evaporating to record low levels. Dhillon was back in Canada after his trip to India, doweries in hand from two marriages, and anxiously awaiting the $200,000 payoff on Parvesh’s life.

On Tuesday, June 27, a man named Cliff Elliot left his home in Burlington, a city sitting hard to the north of Hamilton along the Lake Ontario shore. He drove to work past parched brown lawns. No rain for more than a month. On this day, though, Elliot saw pellets of rain hit his windshield.

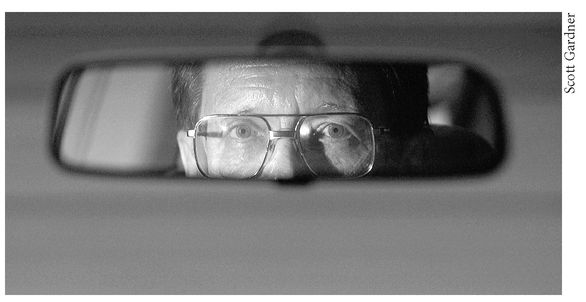

At 61 he was tall, bookish in manner. He wore glasses and had thick, dark brown hair, brushed back. People commented on

it, the absence of even a speck of gray. How do you do it, Cliff? He never dyed it. Cliff’s mother hadn’t gone gray until well into old age. It reflected Elliot’s cool under pressure. He retained a British accent, having been born on a late summer’s evening in Buckinghamshire, a couple of floors over top of the English pub his parents owned. His father, George, flew in the RAF against Hitler’s Luftwaffe and lived to tell about it, and eventually worked on the top secret Avro Arrow fighter jet project in Canada. Dad was still around, still sipped a shot of whisky each night.

it, the absence of even a speck of gray. How do you do it, Cliff? He never dyed it. Cliff’s mother hadn’t gone gray until well into old age. It reflected Elliot’s cool under pressure. He retained a British accent, having been born on a late summer’s evening in Buckinghamshire, a couple of floors over top of the English pub his parents owned. His father, George, flew in the RAF against Hitler’s Luftwaffe and lived to tell about it, and eventually worked on the top secret Avro Arrow fighter jet project in Canada. Dad was still around, still sipped a shot of whisky each night.

Insurance claim investigator Cliff Elliot

Elliot was an insurance claims investigator. This morning he was en route to east Hamilton, following up on one of the dozen or so cases on his docket. He had started in the business in 1958. Not too glamorous in the early days. There was the time he visited a woman who claimed her diamond ring was lost. He peered under her carpets on his knees, took apart pipes under the kitchen sink—

apologies, ma’am, just be a few minutes

. It was probably the neatest home he had ever seen, until he got through with it. The claim was legit. Eventually Elliot specialized in death claims. At one point in his career he directed all death claims in Canada for a company called Equifax. In 1992 he surprised his employer, Keyfacts International, by taking a retirement package. Keyfacts urged him to stay on. They needed Elliot, his thick black book packed with contacts.

apologies, ma’am, just be a few minutes

. It was probably the neatest home he had ever seen, until he got through with it. The claim was legit. Eventually Elliot specialized in death claims. At one point in his career he directed all death claims in Canada for a company called Equifax. In 1992 he surprised his employer, Keyfacts International, by taking a retirement package. Keyfacts urged him to stay on. They needed Elliot, his thick black book packed with contacts.

Now he worked part time, easing into retirement, paid by the case. One of the new ones involved a claim on a young Punjabi-Canadian

woman. She had died four months earlier, in February. Her name was Parvesh Dhillon. Primerica Life Insurance Company needed more documents before paying the $200,000 benefit to her husband, Sukhwinder Dhillon. It seemed a straightforward case. Elliot turned off Barton Street onto Berkindale Drive, stopped his Ford Tempo in front of Dhillon’s house. There was a red fire hydrant in the yard. Elliot pulled ahead a little farther and parked in front of the next house, the one that had two small decorative statues in the front yard.

woman. She had died four months earlier, in February. Her name was Parvesh Dhillon. Primerica Life Insurance Company needed more documents before paying the $200,000 benefit to her husband, Sukhwinder Dhillon. It seemed a straightforward case. Elliot turned off Barton Street onto Berkindale Drive, stopped his Ford Tempo in front of Dhillon’s house. There was a red fire hydrant in the yard. Elliot pulled ahead a little farther and parked in front of the next house, the one that had two small decorative statues in the front yard.

Dhillon answered his door to see the lanky Elliot on the step. The wide dark eyes affected a puzzled, even fearful, look, Dhillon’s natural shield against strangers. Dhillon nodded in greeting. Elliot politely went into his spiel.

“Good morning, Mr. Dhillon, I am Clifton Elliot of Keyfacts International. I’m here for you to sign some documents. It will help expedite the processing of the claim on your deceased wife, Parvesh.”

Dhillon quickly, excitedly, invited Elliot inside, talking rough but passable English to him. The life insurance deal. Finally. They sat at the kitchen table. Parvesh had collapsed just over there, on that carpet, five months earlier. “How did your wife die, Mr. Dhillon?”

“She was at this table,” Dhillon said, gesturing. “She started to shake, then fell to the floor. She died at hospital.”

Elliot studied the husband’s face and waited for the words to come from his mouth. And waited.

I am devastated … If you find anything out about her death, please, please let me know, would you?

Those words didn’t come. No, Mr. Dhillon explained away his wife’s recent death rather blandly. Where was the pain, the puzzlement that her death remained a mystery? Where was the intensity that Mr. Dhillon showed at the door when the strange man came knocking? Elliot had no idea how Parvesh died. But her husband of—what did the form say, 12 years?—didn’t know much about it, either. And Elliot was surprised that Mr. Dhillon didn’t seem curious about it at all.

I am devastated … If you find anything out about her death, please, please let me know, would you?

Those words didn’t come. No, Mr. Dhillon explained away his wife’s recent death rather blandly. Where was the pain, the puzzlement that her death remained a mystery? Where was the intensity that Mr. Dhillon showed at the door when the strange man came knocking? Elliot had no idea how Parvesh died. But her husband of—what did the form say, 12 years?—didn’t know much about it, either. And Elliot was surprised that Mr. Dhillon didn’t seem curious about it at all.

You work in this business long enough, you read people. Cliff Elliot always insisted on seeing beneficiaries in person to read the

tea leaves, to act as a human lie detector, listening to their tone of voice, observing whether facial lines crinkled with emotion or stayed smooth in a forced cool. He would show up 30 minutes early for an appointment, or unannounced. Truth comes best off the cuff. “Terribly sorry,” he would say. “Just a tad early, I’m afraid.” Under different circumstances, in another life, he could have worked for Scotland Yard. The gentleman investigator, the Velvet Hammer.

tea leaves, to act as a human lie detector, listening to their tone of voice, observing whether facial lines crinkled with emotion or stayed smooth in a forced cool. He would show up 30 minutes early for an appointment, or unannounced. Truth comes best off the cuff. “Terribly sorry,” he would say. “Just a tad early, I’m afraid.” Under different circumstances, in another life, he could have worked for Scotland Yard. The gentleman investigator, the Velvet Hammer.

Most of his cases were for accidental death. A man dies in a car accident. For the purposes of the life insurance claim, however, did he die as a result of the crash, or might he have had a heart attack in the car just before it? He needed autopsy and coroner’s reports to find out. Sometimes he followed the tracks of police investigators who went before him. Sometimes he led the police. There was the Burlington man years back who made a claim after saying his wife was stabbed by thugs in a parking lot. In due course the man skipped off to Las Vegas. Elliot came calling about the claim, asked questions, gathered medical records, chatted with travel agents, police. Ultimately, the man was jailed for homicide.

There was another case—an East Indian woman filed a claim for her husband’s death, saying he was kidnapped during a visit to India and killed. Elliot showed up at her house, asked to see travel documents and phone records in order to put the husband in India and confirm his disappearance. He told the wife, in his polite way: “I will contact the Canadian High Commission in New Delhi. Perhaps they have some information on the case.” She got cold feet. Miraculously, the husband showed up in Canada shortly afterwards. Turns out he escaped his captors and survived. Imagine that! The insurance claim was withdrawn and Elliot phoned the police. He stood to gain little from extra work chasing people who were out to cheat the system. It was simply part of who he was.

Elliot spent about 20 minutes in Dhillon’s house. Then he left with signatures on several documents. His verdict? Dhillon knew more about the death than he let on. Life insurance claims are void for a suicide if they happen within the first two years of the policy. Had Parvesh taken her own life by overdose? Died of an allergic reaction? Whatever it was, Dhillon knew something,

but was not telling. Elliot got back in his Tempo and drove to Hamilton General Hospital to order records concerning the death of Parvesh Dhillon. He also requested coroner’s records and those of Parvesh’s family doctor.

but was not telling. Elliot got back in his Tempo and drove to Hamilton General Hospital to order records concerning the death of Parvesh Dhillon. He also requested coroner’s records and those of Parvesh’s family doctor.

When the hospital records came back three weeks later they offered little help. The cause of her death was listed as anoxic brain damage—lack of oxygen to the brain—but the root cause was unknown. The hospital drug screen showed Parvesh had not died from street drugs. The reporting coroner had not ordered toxicology tests in Toronto. The law did not require them. Elliot wanted to dig deeper. He called Primerica, the company that had insured Parvesh Dhillon’s life. Would they like him to look into the case further, or were they content to pay Mr. Dhillon?

“The reports say we don’t know how she died,” he said. “She could have taken bottled Aspirin or something for all we know. It hasn’t been checked, and for some reason the coroner didn’t order additional toxicology.” The voice on the line agreed that it sounded a little unusual, but by the end of the summer, Primerica had the documents ready to process Dhillon’s claim. The company decided not to pursue any further investigation. Her husband could receive his $200,000.

Cliff Elliot had more than a dozen other cases on the go, plenty else to keep him occupied, and retirement loomed. But he was not pleased. It just didn’t feel right. After getting the word from Primerica that Dhillon’s check was being processed, Elliot drove to his downtown Hamilton office. He carried the brown folder over to the metal filing cabinet, the one with all the lives inside. He fingered the insurance file folders in a drawer until he hit D for Dhillon. He slid Parvesh’s file into its resting place. The case was closed.

Dhillon decided to take another trip to India, a short one this time. He flew out of Toronto on July 28 and returned August 11. A visit to the market in Ludhiana for more

kuchila

? Another deal in the works? Soon after he returned, finally, the payoff arrived—the

check from Primerica dated August 25, 1995, for $202,260.67. His biggest deal ever. He also would soon receive $15,000 from Parvesh’s workplace life insurance policy. He had already emptied her personal account of $38,000 in savings that she had kept from him. For good measure, he forged the signature of Parvesh’s father, Hardev, in order to write himself a $1,000 check from the old man’s account and duly cashed it. He put $50,000 in a term deposit for both Harpreet and Aman, his young daughters. A perfect move. It looked charitable, but happened to allow him to keep his hands on the money, avoid paying tax on it, and skim interest earned on the investment to transfer into his own account. His bank adviser urged him not to do it. Revenue Canada frowned on the practice. What did Dhillon care what Revenue Canada, his adviser or anyone else thought? He was, as the car dealers put it, on a roll! On fire!

kuchila

? Another deal in the works? Soon after he returned, finally, the payoff arrived—the

check from Primerica dated August 25, 1995, for $202,260.67. His biggest deal ever. He also would soon receive $15,000 from Parvesh’s workplace life insurance policy. He had already emptied her personal account of $38,000 in savings that she had kept from him. For good measure, he forged the signature of Parvesh’s father, Hardev, in order to write himself a $1,000 check from the old man’s account and duly cashed it. He put $50,000 in a term deposit for both Harpreet and Aman, his young daughters. A perfect move. It looked charitable, but happened to allow him to keep his hands on the money, avoid paying tax on it, and skim interest earned on the investment to transfer into his own account. His bank adviser urged him not to do it. Revenue Canada frowned on the practice. What did Dhillon care what Revenue Canada, his adviser or anyone else thought? He was, as the car dealers put it, on a roll! On fire!

Dhillon received payments from Parvesh’s life insurance policies.

In September, Dhillon went to the tax office in Hamilton and lied about his income flow, low-balled it in order to claim a Goods and Services Tax rebate. The Worker’s Compensation benefits from his claim of injury in 1991 continued, and he was still selling cars. Given his mountain of debt, Dhillon was hardly set for life. But he had money to play with and two young wives in India to do with as he pleased. On November 2, 1995, Dhillon filed an immigration claim to bring his third wife, Kushpreet, to Canada. On November 7, he closed a deal for $66,100 to buy a small house on Main Street East, just east of Ottawa Street. He would rent out rooms in the house and use a large paved area behind it

to park his cars. No more crowding used vehicles in his driveway on Berkindale Drive. Finally he had his dealership. He’d made it. He booked another trip to India for December. This would be a much longer visit.

to park his cars. No more crowding used vehicles in his driveway on Berkindale Drive. Finally he had his dealership. He’d made it. He booked another trip to India for December. This would be a much longer visit.

Other books

Lime's Photograph by Leif Davidsen

Wolf Totem: A Novel by Rong, Jiang

Scandalous by Karen Erickson

The Smoky Corridor by Chris Grabenstein

Tick,Tock,Trouble (A Seagrove Cozy Mystery Book 5) by Leona Fox

Mallara and Burn: On the Road by Frank Tuttle

Winter Ball by Amy Lane

Green Kills by Avi Domoshevizki

Dueling With the Duke (Brotherhood of the Sword) by Robyn DeHart

The Impaler by Gregory Funaro