Poison (34 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

Korol grimaced. Strychnine was the essential link to Ranjit and Parvesh. The twins’ deaths, which he and Dhinsa had worked so hard to chase down, now raised more questions than answers. He tried to stay positive. They still might be able to make their case. The chemical cocktail was surely lethal to newborns. And it doesn’t just show up in the tissue for no reason. Someone had given it to them. And surely it was more than a coincidence that two healthy boys would both die within hours of a guy like Dhillon visiting them.

The preliminary hearing was the longest one anyone could remember, dragging through the summer and then into the fall of 1998. Dhillon remained confident he would get away with everything. The Crown had been calling witnesses from India, flying them over to testify, to repeat what they had told Korol and Dhinsa about Dhillon. That was fine with him. He had secretly arranged for one of the witnesses, Rai Singh Toor, father of Kushpreet, his dead third wife, to swear to an affidavit in India. In it, Rai said that he did not suspect Dhillon in Kushpreet’s death. The Crown and detectives were not aware of the affidavit.

Dhillon saw Warren Korol sitting in court each day. Some days, before the judge entered the room, Dhillon turned around in the prisoner’s box and smiled, mouthed curses at him, gave him the finger. Korol regularly met unsavory characters, but Dhillon was the worst: a liar, a coward, a killer to whom anyone

was expendable, particularly those closest to him. In Korol’s book, Dhillon crossed all the lines. Crooks, being crooks, lie and cheat. But there was still an etiquette, a mutual respect, he expected even from them. Korol had a job to do. It shouldn’t get personal. He got in a suspect’s face when the occasion warranted, but that was rare, and rising to Dhillon’s taunts would just put the case in jeopardy.

was expendable, particularly those closest to him. In Korol’s book, Dhillon crossed all the lines. Crooks, being crooks, lie and cheat. But there was still an etiquette, a mutual respect, he expected even from them. Korol had a job to do. It shouldn’t get personal. He got in a suspect’s face when the occasion warranted, but that was rare, and rising to Dhillon’s taunts would just put the case in jeopardy.

Korol was certain Dhillon had people make crank phone calls to Kevin Dhinsa’s home. The bastards would say something on the phone about Kevin’s father, who had recently died. It was beyond the pale. You just don’t do it. Korol assigned officers to keep an eye on Dhinsa’s house. Korol felt his anger the strongest when Dhillon’s niece, Sarvjit, was testifying. She had told the police so much about her uncle. And she had confided in Korol, poured her heart out to him. She called one day, sobbing, said her family had forced her to marry a “stupid man. I feel like a puppet.”

“Why did they force the marriage on you?” Korol had asked.

“To get me permanent immigration status in Canada.” She went on, “Whenever I am in front of Detective Dhinsa, I feel disgraced because I am not acting like an Indian woman should.”

“Don’t feel like that,” Korol had told her.

Now, in the witness box under oath, Sarvjit denied everything she had said about Dhillon, even things for which there was already ample proof, even denying she herself had ever been married. Korol sat in astonishment. Dhillon. He put her up to this. The kid was terrified. Sarvjit stepped down from the stand. Dhillon, in the prisoner’s box, glanced over his shoulder at Korol, looked him in the eye, and grinned. Korol felt the heat rise under his skin. He felt sick. He hated Sukhwinder Dhillon.

The case was not going well. Bentham, Korol, and Dhinsa felt deflated. All the evidence was amassed, but some witnesses altered their statements from what they had told the detectives—especially those brought over from India. Dhillon was intimidating witnesses by threatening their families back in Punjab. In Panj Grain, Sarabjit’s brother received a warning over the phone: “Your family is giving evidence against Dhillon. You should know that you could be killed for it.”

In Ludhiana, a cousin of Kushpreet’s named Raju also got a call: “Get your parents to change their testimony. Or you’re dead.” His parents had been at Kushpreet’s funeral, had spoken to Dhillon. One night in Ludhiana, Raju was attacked in an alley, hit over the head. He was sure it was Dhillon’s friends.

Several times, Bentham had to invoke Section 9(1) and (2) of the Canada Evidence Act, asking the judge to allow him latitude to cross-examine his own witnesses on inconsistent statements. Only by using that hammer was Bentham able to get witnesses to talk, for example, about the symptoms seen in Kushpreet right before she died. The mood was not upbeat. Dhillon’s confidence was not out of line, it seemed. On a positive note, a fresh face was about to join the Crown team and pump new life into the case.

Raju Mundi, Kushpreet’s cousin, in Ludhiana

Hamilton’s chief Crown attorney, Dave Carr, called the young lawyer into his office. The two prosecutors on the Dhillon case were Brent Bentham and Linda Templeton. But in the middle of the preliminary hearing, Templeton was promoted to the bench. Bentham was in charge and he needed a second lawyer. Tony Leitch, a young prosecutor at just 33, had an inkling that he might at some point be put on the high-profile case.

“Okay, Dave,” he said. “What am I working on?”

Not all Crown attorneys, or lawyers, were built like Leitch. A football defensive end in college, he cut an imposing figure. He had big hands, size 15 ring finger, wore his hair cropped close. And his high-octane personality was a contrast to the understated Bentham. Tony Leitch loved a challenge, relished complex,

demanding cases. Dhillon certainly qualified. He approached the job like a student on an all-night study session.

demanding cases. Dhillon certainly qualified. He approached the job like a student on an all-night study session.

Warren Korol would slap a nickname on him during the trial. “Hey, who are you, the law-talkin’ guy?” Korol said after Leitch mentioned an obscure legal point. The Law-Talkin’ Guy stuck.

Leitch was not yet privy to all the evidence, but he was aware of the case and had already thought about it. It was too complicated to be a slam dunk, but he still thought it was a solid case for the Crown, notwithstanding the problems that had already cropped up. The key, he believed, was keeping all five deaths before the jury: Parvesh, Ranjit, Kushpreet, the twins. The issue of motive was important, but not as much as the improbability of coincidence: 1) Five people are poisoned. 2) The common denominator is Sukhwinder Dhillon. And in two of those deaths, he had a direct financial motive. A great case.

Growing up, Tony Leitch never felt pressure to succeed, not overt pressure, anyway. Fred Leitch, his dad, was an easygoing guy. Just do what you want to do, he told his son, and I’m sure you’ll be good at it. But how many kids get invited into a judge’s chamber at seven years old? The judge said to little Tony, “You know, your father is a very important man.” And Tony burst out laughing.

Fred Leitch was a defense lawyer, and a well-known one at that. He always had legal papers strewn around the house, and Tony would hear the sound of his dad rustling about at four in the morning. At 13 years old, Tony looked out the window one day and saw the police guards. Fred was defending a murder case, and threats had been made against his family.

Tony knew the expectation was that he would succeed. Instead, he slapped success in the face. In 1984 he attended the University of Western Ontario, popular for its fraternities, sororities, and football, a school dubbed “The Country Club” for its well-heeled, party-loving student body. He wanted to play on the perennial powerhouse football Mustangs, party, and study—in that order. He spent much of his time either on the football field or on Richmond Street at the Ceeps, the cramped student pub where they served cheap but cold draught and bodies lurched to and fro in a hot crush until closing time, then poured out onto the street for Greek at Sammy’s Souvlaki shack. As

for football, Tony ended up sitting on the bench. And he almost failed first year. In second year, he failed all five of his courses.

for football, Tony ended up sitting on the bench. And he almost failed first year. In second year, he failed all five of his courses.

Then something clicked. Tony married young, settled down, and got back into Western. He turned the energy he had previously burned on football and partying to his books and dominated the debates in political science classes, where his booming voice and articulate delivery overwhelmed all comers.

It all came together, his ability to think on his feet, to adjust to the situation, to instantly shift from one argument to another, recognize holes in his opponent’s line of reasoning. He made the dean’s honor list the next year. When it came time to apply to law school, he had to use his rhetorical skills to explain those two lost years at Western. If Leitch had unconsciously rebelled against his father’s success, that was over now, except that, while Fred Leitch defended the accused, Tony prosecuted them.

If there was ever a case that could satiate his appetite for challenge, it was Dhillon’s. Dave Carr, the head Crown attorney, assigned Leitch to help Brent Bentham prosecute. They complemented each other perfectly; one measured and taciturn, the other outgoing, energetic. They would need to marshal all their resources—and patience—for this one.

Assistant Crown attorneys Brent Bentham (left) and Tony Leitch

CHAPTER 19

PARVESH’S SECRET

All things considered, opined the elderly man with the deep voice and thick Austrian accent, ricin is probably the most effective poison for murder.

Ricinus communis L

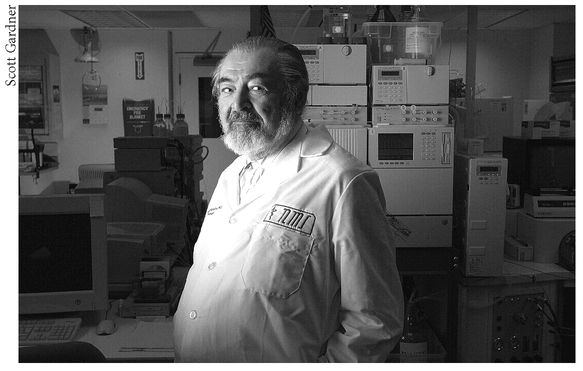

. It comes from the seeds of the castor bean plant. The victim becomes progressively ill—abdominal pain, vomiting, bloody diarrhea—but death is delayed three days or so. Amazing, really. Hamilton homicide detective Steve Hrab listened intently as Dr. Fredric Rieders spoke at the conference. It was October 1998, the preliminary hearing in the Dhillon case extending into its sixth month. Rieders had an international reputation as a toxicologist. Three years earlier, he had testified for the defense in the O.J. Simpson trial, helping lawyer Johnnie Cochran make the scientific case that Simpson was framed by the LAPD, that blood evidence found at the crime scene was tainted.

Ricinus communis L

. It comes from the seeds of the castor bean plant. The victim becomes progressively ill—abdominal pain, vomiting, bloody diarrhea—but death is delayed three days or so. Amazing, really. Hamilton homicide detective Steve Hrab listened intently as Dr. Fredric Rieders spoke at the conference. It was October 1998, the preliminary hearing in the Dhillon case extending into its sixth month. Rieders had an international reputation as a toxicologist. Three years earlier, he had testified for the defense in the O.J. Simpson trial, helping lawyer Johnnie Cochran make the scientific case that Simpson was framed by the LAPD, that blood evidence found at the crime scene was tainted.

Born in Vienna, he was drafted to serve in the German army in 1939. But shortly before his papers arrived, the 17-year-old graduated from high school and as a gift from his family traveled to New York City to visit an uncle. War broke out in Europe, and when he did return, it was fighting for the Americans in the 20th Armored Division, his German language skills a big asset.

Hrab had come to Albany, N.Y., to attend a seminar for homicide investigators. At the end of the day, Hrab found himself sitting beside Rieders. Ricin’s greatest advantage, he continued, is its short retention time: the speed with which it leaves the body. That’s why it was a favorite weapon of the infamous Soviet KGB. They used it in the 1978 “umbrella assassination” of Bulgarian defector Georgi Markov.

Hrab engaged Rieders with more questions. The toxicologist talked about his laboratory in Pennsylvania, where he used equipment so sensitive it was capable of detecting toxins weighing as little as one picogram—a trillionth of a gram—in human tissue. That meant his equipment was far more sensitive than what the CFS in Toronto had to offer. Impressed, Hrab talked about the Dhillon case. Symptoms pointed to strychnine, but Parvesh’s body tissues were two years old when they were tested and no poison was found in them.

Dr. Fredric Rieders, toxicologist

Other books

From the Grounds Up by Sandra Balzo

Castle Perilous by John Dechancie

The Essential Faulkner by William Faulkner

The Happy Birthday Murder by Lee Harris

Dream Man by Linda Howard

Alpha by Rachel Vincent

Darkest Mercy by Melissa Marr

Shifter Wars by A. E. Jones

Gambler by S.J. Bryant