Pearl Harbor Christmas (7 page)

Read Pearl Harbor Christmas Online

Authors: Stanley Weintraub

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #United States, #20th Century

RELATIONS WERE MUCH LESS WARM with their new allies, the Germans. Neither side trusted the other, although a thriving business existed in trading in raw materials like rubber, which the

Reich

needed for war equipment the Japanese could import or copy. The Germans also wanted the newest Japanese torpedoes that had been so successful at Pearl Harbor, and the “more than 20 British aerial torpedoes” captured by the Japanese in Malaya at Kota Bharu. Admiral Paul Wenneker, the German naval attaché in Tokyo, was asked in exchange “about the state of completion of the German aircraft carrier

Graf Zeppelin

. The Japanese Navy would welcome it if this vessel could be transferred. They do not think,” Wenneker wrote, “that the vessel can play any role in the conduct of German naval strategy any longer.... If the vessel could be brought to the Pacific under Japanese control, it can play a much greater role. I advised [Vice Admiral Minoru] Maeda to arrange for the subject to be discussed in Berlin.”

Flugzeugträger A

—the unfinished

Graf Zeppelin

—was the farthest along of two carriers that the German admiralty had been building at Baltic ports. Hitler had ordered work stopped in order to conserve manpower and steel for U-boats, then restarted, then halted again, but he refused to let the warship out of German hands. The British had bombed it once, unsuccessfully. It would be scuttled in harbor in 1945, then raised by the Russians. Its hulk was towed to Leningrad to be scrapped.

German freighters long at sea ran the porous British blockade, usually flying spurious foreign flags, from Bordeaux and around Cape Horn into the South Pacific east of New Zealand and up through the Japanese-mandated Carolines and Marianas to Yokohama. (Italian freighters also slipped through, including one then in port, the

Orseolo

.) Despite the risks taken by the

Kriegsmarine

, Admiral Wenneker had constant bureaucratic tangles with Japanese ministries regarding customs, finances, and security. The newest problem was that of the freighter

Rio Grande,

“to make it possible for the crew to be allowed to go ashore at last.... The German side cannot permit this kind of [suspicious] treatment toward the other ships expected to arrive here” and for permission “to make the return trip as soon as possible.” Its cargo had yet to be unloaded. Wenneker worried about American submarines now reported offshore—although he would have worried less had he known how faulty their fuses were.

BY EVENING, his Fourteenth Army slowed in high seas, General Homma had landed all his forces aboard transports in Lingayen Bay, but he had not yet come ashore himself. Ordered out of hazardous Manila Bay toward the Dutch East Indies, Admiral Thomas Hart’s pathetic Asian Fleet remnant of three cruisers and twelve destroyers, most of them four-stackers of World War I or postwar vintage, were voyaging toward Surabaja in eastern Java. Many would not survive the first months of engagement. Their first port of call had been Balikpapan on the southeastern coast of Borneo, where the destroyers

Ford

and

Pope

received a flash-lamp message from Lieutenant (jg) Henry F. Burfeind: “Greetings to my fellow [Annapolis] classmates. Left

Pillsbury

in Manila, ordered to

Mareschal Joffre

to take her south. See you in Surabaja.” The unmilitary

Mareschal Joffre

was a 14,500-ton, rat-infested Vichy French freighter with a foreign crew who knew no English that was seized by American authorities when the war began. An ensign and twenty-eight enlisted sailors, most of whom had been wounded in the bombing of the Cavite naval base, were added to Burfeind’s crew. En route to Balikpapan it was scouted by two Japanese planes, then left alone. It would continue on to Australia and New Zealand with its Chinese and Indochinese crew and make it to pier 23 in San Francisco via a refueling stop at Acapulco in Mexico, where it would leave without paying a docking fee. In California it was converted into a troopship renamed the

Rochambeau

. Many of its foreign crew joined the navy there, were paid, and issued uniforms.

SAILING FROM the Thames Estuary was the nine thousand–ton Norwegian-flag tanker

Regnbue (Rainbow)

, empty but for ballast, ordered to load fuel at Corpus Christi, Texas. Harry Larsen, the chief engineer, complained as they raised anchor about the horrors at sea at Christmas without “newts or frewts or yin.” The ship’s chandler in London could supply no nuts or fruit, but a lighter had brought out a case of gin and two cases of whiskey.

New Yorker

journalist A.J. Liebling, hitching a ride home, was assured that although “ordinarily” no liquor was served aboard ship “except to pilots and immigration officers, Christmas was always an exception.” The

Regnbue

proceeded in a column of eight, one of five groups, with four corvettes as escort. No one expected the ships to remain together in the stormy Atlantic.

“Much colder as we go north,” Oliver Harvey of Anthony Eden’s party wrote from their train toward Murmansk, and their risky convoy home. “Meals still muddled—we had two breakfasts in succession at 9.30 and 1.30 but no lunch. However we hope to get dinner straight.”

To their south, the winter war had already gone on so unexpectedly long for the Germans—Hitler had expected it to be over by the time the first snows fell in Russia—that he had issued a much-belated proclamation from “Führer Headquarters,” soon picked up worldwide when it was broadcast on Berlin radio:

German Volk!

While the German homeland is not directly threatened by the enemy, with the exception of air raids, . . . if the German Volk wishes to give something to its soldiers at Christmas, then it should give the warmest clothing that it can do without during the war. In peacetime, all of this can easily be replaced. In spite of all the winter equipment prepared by the leadership in the

Wehrmacht

and its individual branches, every soldier deserves so much more!

Acknowledging the existence of Christmas to make the appeal more subtle, Hitler was preparing the public to give until it hurt. In a further directive he decreed the death penalty for anyone “who gets rich” profiteering from the expected flood of offerings to be managed by Joseph Goebbels, who had persuaded Hitler to inaugurate the clothing drive. It could not have been easy for the Führer to switch from his usual arrogance to covert admission that things were suddenly going wrong.

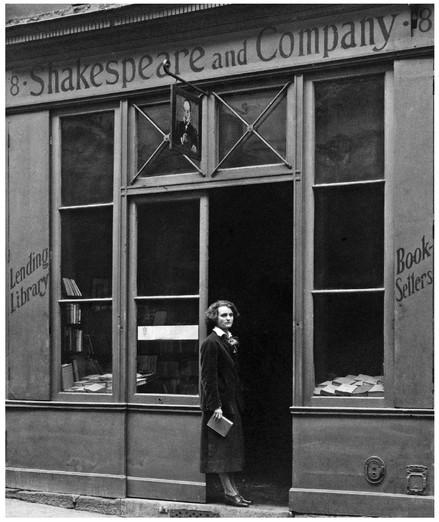

IN OCCUPIED PARIS a grey German military vehicle stopped at the entrance to Shakespeare and Company, Sylvia Beach’s cluttered bookshop at 18, rue de l’Odéon. A

Wehrmacht

officer wanted to confirm that a book he wanted—perhaps as a Christmas present—was still for sale. Enemy registration for Americans instituted after Pearl Harbor had closed on the 17th, but Miss Beach, a dowdy fifty-four and in France since 1920, was still in precarious business. Indoors he demanded, in fluent English, “I want that copy of

Finnegans Wake

you’ve got in the window.”

Sylvia Beech below her Shakespeare and Company bookshop sign in Paris, 1942.

Courtesy Princeton University Special Collections

“Well,” she retorted, “that’s the only copy left in Paris, and you can’t have it.... You don’t know Joyce.” She recalled his anger rising as he insisted, “But we admire James Joyce very much in Germany.” Although she refused to sell the book, the officer, surprisingly, strode out rather than confiscate it, “got into his great car, his great military car, surrounded with other fellows in helmets, and drove away.” She determined to hide it.

CHURCHILL’S REMAINING RETINUE debarked at Newport News from the

Duke of York

and received its first taste of wartime America on a special train to Washington, which arrived just after midnight. What they saw en route resembled nothing left behind in austere, battered wartime Britain. Through placid Virginia, lights of homes, highways, shops, and even outdoor Christmas trees flashed by almost eerily to travelers accustomed to blackouts. The PM’s military secretary, General Hastings Ismay, had remained in London as Churchill’s resident uniformed deputy, but Ismay’s associate, Colonel Ian Jacob, shepherding the traveling party, recorded happily “a first-rate sandwich dinner consisting of cold chicken, two hard-boiled eggs, salad, coffee and fruit.” Real eggs, rather than the powdered substitute, were rare at home.