Pearl Harbor Christmas (11 page)

Read Pearl Harbor Christmas Online

Authors: Stanley Weintraub

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #United States, #20th Century

Between each course were further skoals, in which the teetotaler Methodist captain did not join. Willem Petersen “brought out a couple of songbooks that he had got from a Norwegian church and suggested we sing some Christmas hymns,” duly done “without much pleasure,” following which they ate mounds of doughnuts and “a lot of jello covered with vanilla sauce” and drank more gin. Feeling awkward after the hymns, the men’s faces remained rigid and solemn until the steward brought in triple portions of gin with lump sugar and cherries. Whiskey was served straight as a dessert liquor. The men sang Norwegian folk songs between skoals until the captain asked “our American friend” to sing a song from his own country—“My Old Kentucky Home.” Liebling knew few of the words, especially after all the “yin,” but happily three crewmen began singing three different Norwegian songs at the same time. Then others drifted in from their dinner groups, all now unable to appear Christmas-solemn—“first the argumentative carpenter, then the boatswain with the cackle, and finally the pumpman, a tall fellow who looked like a Hapsburg and spent his life shooting compressed air into clogged oil tanks.”

Men began leaving their tables to stand—if they could—their watches. Announcing, “I am a Commoonist, so I want you to love these fellers,” the steward handed out bottles of Old Angus whiskey and Christmas greetings from the Norwegian government-in-exile, each with the facsimile signature, “Haakon, Rex.” The crewmen aft were all wearing blue stocking caps which had come to dockside in a Christmas gift package with cards identifying the Santa headgear as having been knitted by Miss Georgie Gunn of 1035 Park Avenue, New York City.

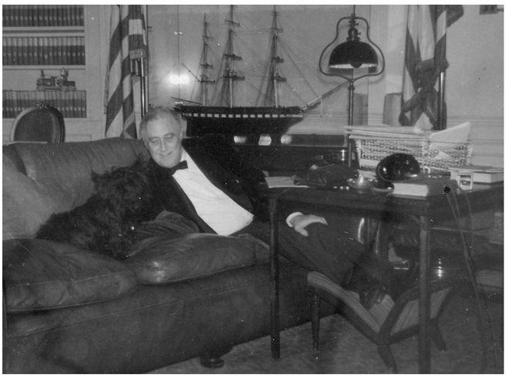

ONCE THE PRESIDENT had awakened, Eleanor hung a Christmas stocking on the mantel in his bedroom for Fala, with rubber bones and other chewable toys. Diana Hopkins had a stocking hung at the fireplace in her father’s bedroom. She was the only resident child in the White House. For FDR and for Hopkins Mrs. Roosevelt had bought and packaged bed capes in Christmas paper. Her husband’s was a navy-blue wool wrap-around with his initials embroidered in red. A deluge of Christmas presents and greeting cards had already been arriving at the White House and at the British Embassy for Churchill, and would continue all week. Box after box of cigars would be posted to the PM, eight thousand cigars in all. Bottles of vintage brandy; gloves, socks and scarves; a box of fresh onions; catnip for the Churchill cat at Chequers; and the inevitable religious tracts. As no one could examine every one of the gifts to determine which may have concealed explosives or poison, for security reasons the Secret Service ruled that only Christmas gifts for the Prime Minister from persons identified and specially cleared could be accepted.

Churchill “was still in deshabille, wearing a sort of zipper pajama suit and slippers,” Stimson wrote. “I had brought maps of the Philippines and explained the location of the different troops on both sides, the course of the campaign, and its probable outcome in a retreat to Corregidor. Eisenhower [who probably did the explaining] then retired and I had a further talk with [Churchill] about other matters.... He explained to me particularly his views on the West African problem.” Churchill wanted a quick takeover of Vichy French Africa, and much of the meetings into January would deal with its attractions—and impossibility.

Franklin D. Roosevelt in his study with Fala, December 1941.

Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library

The military chiefs and their staffs convened at 10:30 A.M. in the imposing marble Federal Reserve Building near the War and Navy departments, taking up points in order of assumed priority. Admiral Harold (“Betty”) Stark began by declaring that the British Isles were to be protected “at all cost.” Island defenses needed more deterrent capacity, as invasion remained a possibility as long as the Germans held the Channel ports in France. Field Marshal Dill responded that the defenses were “constantly being improved.” When Stark noted that American heavy bombers to be sent to Britain would be manned by American crews, Air Marshal Portal objected that it was not part of the original agreement. He saw inexperienced American airmen as a burden, even if experiencing the real thing would make them useful. Stark explained that those planes with their crews would supplement aircraft to be supplied for British use, and General Marshall reminded Portal that the PM himself had noted how important externally a visible American presence would be, including the American divisions which would also be assigned, subject to “the availability of tonnage.”

The conferees discussed the relief of British troops in Iceland, and General Gerow advised that the changeover could be completed by March—but again, everything hinged on shipping and the havoc wrought by German subs in the North Atlantic. More patrols were needed, said Stark. “We just don’t have any destroyers to spare, and in fact have fewer for our own needs.” Like Iceland, Greenland would be a staging area for air transport, General Arnold added. One field was ready and another was being prepared. When North Africa again came up, Marshall observed that “a token [American] force as part of the British forces would be feasible, but he could not [safely] put a lone regiment on the coast of Africa.” Obviously Vichy French Africa remained a target many months away.

When the conferees turned to the Pacific Rim, Field Marshal Dill suggested that “with reinforcements, the British would be able to hold Johore State,” on the Kra Peninsula above Singapore. No one disputed him. (Reinforcements would continue to arrive, as late as February 5, little more than a week before the abject surrender.) General Arnold was asked about the possibility of bombing Japan from unoccupied China. There was no point in it, he said, unless American air power was “strong enough to create substantial damage.... Unsustained attacks would only tend to solidify the Japanese people.” (Within weeks his views about a token operation would change, leading to the daring Doolittle raid in April and its likely impact in June on the climactic battle off Midway Island.) The aircraft carrier situation, Stark advised, was “very bad, and that . . . the Navy was making plans to convert passenger ships and tankers into airplane carriers.” Twenty other matters were discussed, but the four Churchill/Chiefs of Staff memoranda were deferred for further study, and the meeting adjourned for a late lunch.

Churchill knew that he had a Christmas Eve speech to deliver at the White House tree lighting and worked on it between compulsive trips to his Monroe Room map center. Red dispatch boxes were constantly arriving from the Embassy, and further reports from the President’s staff. Promising news came from Russia, where the German drives on Moscow and besieged and desperate Leningrad were stalled, and from Libya, where Axis forces were retreating from Benghazi and heading for Tripoli while waiting for air and land reinforcements from Russia, where winter had made them of little use. Elsewhere the Japanese were pushing into Burma, endangering the supply route north into China, and moving southward against little resistance in Malaya. Hong Kong was near surrender, trapping Canadian troops sent there by Churchill belatedly and sacrificially, and the Netherlands Indies were being penetrated at multiple points, with little hope, despite the dwindling Dutch navy, to save any of the islands. The PM moved his pins about.

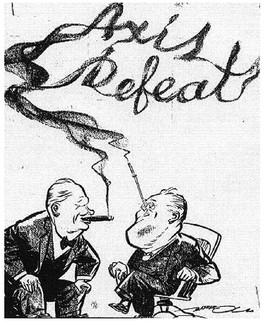

Determined not to be without his own map room, the President ordered one created, and Lieutenant Robert Montgomery of Naval Intelligence, a reservist out of Hollywood for the duration, was assigned to the job. Space was limited; toilets and sinks were removed from a ladies’ cloakroom in the basement, as Montgomery superintended the conversion of a ladies’ cloakroom in the basement into a secure information center, staffed by a joint Army-Navy team under Captain John McCrea, a new naval aide to the President. The Army Signal Corps would run it as a heavily guarded message center, accessible to Roosevelt, Hopkins, and senior military personnel. Montgomery supplemented the color-coded pins on the fiberboard-mounted maps, with special ones for special people. FDR’s was a cigarette holder, Churchill’s a cigar. Stalin was represented by a briar pipe. Franklin Jr.’s destroyer was coded, as well as capital ships. See-through plastic sheets covered land operations, their battle lines changed with a grease pencil. Guam was marked as lost, and other pins confirmed worsening news not yet in newspapers.

“Lighting up.” Churchill and Roosevelt in conference with their iconic cigar and cigarette in long holder.

Cartoon from Vineland, NJ,

Journal,

January 5, 1942.

While working committees met indoors, preparations were being completed for the annual lighting of the outdoor White House (“National Community”) Christmas tree. For Roosevelt, Christmas trees were more than symbols. He raised them for revenue at Hyde Park, listing his occupation on his voting registration form as “tree farmer.” The “planting and the raising and the selling of Christmas trees,” he would tell a press and radio conference, was “close to my heart.” He once thought of making “a radio speech” on the subject, he confessed.

I have some very, very carefully kept books on the subject of Christmas trees—a thing called a check-book. And I pay for the labor of planting these little trees at the age of four years and about six inches high, and I pay a man—oh—about every two years—to go through and keep the briars out of them; and then I pay several people—some of them schoolboys—to go in and cut them off. . . . Along comes a department store or chain store with a truck, and they themselves load these little trees—this is ten years after the planting—into the truck. They take them down to New York, and sell the trees—at a profit.... And then they send me a check.

Prior to each holiday season, his secretary, Grace Tully, recalled, she would write to “one of the chain stores, ... reminding them that the President had trees for sale,” and the stores “would buy the entire year’s output.... He only made a small profit but he hoped one day to produce trees in such quantity that it would be really a profitable venture.”

For security in wartime the Secret Service proposed to have the formidable national Christmas tree, much too tall to be a Hyde Park product, erected in Lafayette Park, a seven-acre expanse across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House, as the event would draw thousands of unidentifiable persons. The President insisted that tradition required the White House lawn. Within the patrolled iron-picket fence around the White House grounds, only those specifically invited would get close to the participants on the South Portico. Even so, guards warned, “No cameras, no packages.” A tent outside the two gates had been set up as a package checking station, but some visitors refused to give up their places in line at the four o’clock opening and dropped their Christmas bundles at the fence, hoping they would find them again afterward. The uninvited could watch from beyond—and under a crescent moon thousands were already gathering in the early winter twilight.

Was a brilliantly lit hazard being created at odds with unenforced wartime brownouts? The White House was assured that no enemy could penetrate Washington airspace. Also, Christmas Eve traditions were exempted in the interest of national confidence. Despite restrictions involving landmarks, the red aircraft-warning light 550 feet atop the Washington Monument remained aglow and could be seen from the White House lawn. At the lighting ceremonies in 1940, realizing that war was approaching from somewhere, and perhaps soon, the President had told the crowd that it was welcome to return in 1941 “if we are all still here.” Many were back.