Pearl Harbor Christmas (18 page)

Read Pearl Harbor Christmas Online

Authors: Stanley Weintraub

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #United States, #20th Century

After dinner, for a change of atmosphere, the President had a movie shown,

The Maltese Falcon,

with Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade. Churchill stayed to the end, in the front row, commenting afterward about a parallel case he had encountered in the 1920s when he was home secretary. Then he retired to draft another major speech for a very different audience.

Mackenzie King had invited the PM to address the Canadian Parliament before the new year recess. Retiring to his rooms to work on the speech, Churchill attempted to open a window. “It was very stiff,” he told Dr. Wilson the next morning. “I had to use considerable force and I noticed all at once that I was short of breath. I had a dull pain over my heart. It went down my left arm. It didn’t last very long, but it has never happened before. What is it? Is my heart all right?”

The discomfort abated. He set to work into the night, then went to bed without alarming Wilson.

December 27, 1941

T

HE ASSOCIATED PRESS reported from a late afternoon MacArthur communiqué that heavy tank battles “raged inconclusively” south of Manila following the Lamon Bay landings. There was no mention that Manila had been abandoned. The tanks were a fiction. An unidentified army “spokesman” for the general advised falsely by radio that the fighting on Luzon was “going well.” Francis Sayre, the American high commissioner for the Philippines, allegedly declared, “We will fight to the last man.” (Sayre was already on Corregidor with his family and staff.)

Traversing the Sulu Sea, the inland Philippines passage already known as “the gauntlet,” the destroyer

Peary

received a radio message that the Japanese were landing at Taytay, the northernmost harbor on long, narrow Palawan, the westernmost Philippine island.

Peary

altered course to the southeast, passing Panay and reaching Negros at 10:30 A.M. As she anchored, a flight of five twin-engine enemy bombers passed overhead, not seeing the four-stacker, whose crew was still spreading pungent green paint with mops. Torpedoman John Fero wisecracked, “Hell, if the Japs can’t see us, they sure will be able to smell us.” The next afternoon off the western tip of Mindanao, two enemy bombers made runs on the destroyer but gunners kept them high and erratic. When

Peary

finally made it to Australia, Fero was seriously wounded in an air raid on Port Darwin. The Japanese sense of smell had improved.

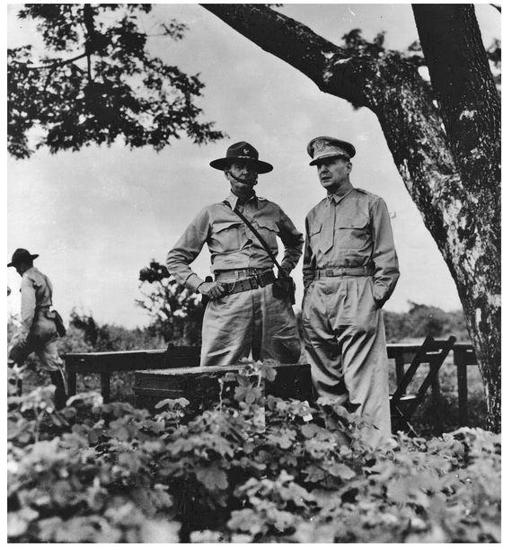

General MacArthur (right) with Major General Jonathan Wainwright, who would become Philippines commander and a prisoner of the Japanese.

Courtesy MacArthur Memorial Library & Archives

AN ANNOUNCEMENT FROM LONDON that the British military had replaced Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham with newly arrived Lieutenant General Sir Henry Pownall left little cause for optimism. He had been deputy to General Viscount John Gort in France in 1940 and survived the evacuation of Dunkirk. Although the report suggested that the appointment would “relieve the minds” of pessimists about the future of Singapore, Pownall had an unenviable and brief command. Like Brooke-Popham, a textbook example of military incompetence, before the end he slipped away to England, and to only mild censure. He would assist Churchill in drafting his self-serving postwar memoirs. Only Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Percival would suffer the PM’s ignominy of losing Singapore to the Japanese. Unlike Brooke-Popham and Pownall, Percival endured a prison camp. One of his ranking companions there would be General Jonathan Wainwright, to whom MacArthur would leave the Philippines.

IN THE MORNING in Washington Dr. Wilson arrived at the White House by taxi, put a stethoscope to Churchill’s chest, and pronounced the incident the night before “nothing serious.” Yet both realized that the PM had survived an angina attack. “You have been overdoing things,” said Wilson, putting the best face on the matter. He would describe the event in his diary, never revealed until it was published twenty-four years later, just after the PM’s death at ninety.

“Now Charles,” said Churchill, “you’re not going to tell me to rest. I can’t. I won’t. Nobody else can do this job. I must. What actually happened when I opened the window? My idea is that I strained one of my chest muscles. I used great force. I don’t believe it was my heart at all.”

“Your circulation is a bit sluggish,” Wilson lied, realizing that Churchill was to leave the next day for Ottawa to address the Canadian Parliament. “You needn’t rest in the sense of lying up, but you mustn’t do more than you can help in the way of exertion for a little while.”

A knock on the door abruptly ended the consultation. It was Harry Hopkins. Wilson edged away with his medical bag into a room where White House secretaries were working and opened a newspaper in semiconcealment. The morning

New York Times

headlined erroneously, “TANK BATTLE SOUTH OF MANILA, LOSSES HEAVY. NEW ENEMY FORCE 175 MILES ABOVE SINGAPORE. CHURCHILL PREDICTS HUGE ALLIED DRIVE IN 1943.” Only the last was close to being accurate. However outnumbered, the Japanese in Malaya were moving at will against demoralized defenders who put up only faltering resistance; and in Luzon MacArthur’s self-composed communiqués suggested stiff resistance and tank encounters that were only imaginative.

Churchill intimated nothing to Hopkins, who may have assumed that Wilson’s visit was routine. “I did not like it,” Wilson wrote of his complicity, “but I determined to tell no one.” Much later (1984) a physician explained to Churchill’s biographer, Martin Gilbert, “The course adopted by Moran [Charles Mc-Moran Wilson became Baron Moran in 1943] on this occasion was quite correct. To have ordered bed rest for six weeks would not have been good therapy as there is no evidence that this does the patient any good and only tends to make them neurotic.”

NOT IN DR. WILSON’S NEWSPAPERS nor in print anywhere else was a conversation between Fritz Todt, Hitler’s armaments minister, the civil engineering expert who had built Germany’s state-of-the-art motorways and was also supervising the construction of an “Atlantic Wall” against the West, and Albert Speer, the Führer’s architect and Todt’s deputy. “I went to see Todt at his house near Berchtesgaden,” Speer recalled. “Given his exalted position it was a very modest place.... He was very depressed that day. He was just back from a long inspection trip to Russia, and he told me how horrified he was by the condition of our soldiers.” Early winter weather, Todt mourned, had turned Russian roads, never much good anyway, into snowbanks and quagmires. He was ordering workers on

Autobahnen

in Germany to put aside their equipment and go east to repair and maintain the Russian road net. The railways, he added, were impeded by snow and poor trackage, and he had seen for himself “stalled hospital trains in which the wounded had frozen to death, and witnessed the misery of the troops in villages and hamlets cut off by the snow and cold.”

Todt confessed that he didn’t see how the war could be won. “The Russian soldiers were perhaps primitive, but they were both physically and psychologically much harder than we were. I remember trying to encourage him. Our boys were pretty strong, I said. He shook his head in that special way he had and said—I can still hear him—‘You are young. You still have illusions.’” Speer was thirty-six; Todt was a burned-out fifty.

Todt assigned logistics in the Ukraine to Speer who, reluctantly, would make his first visit, to the rubble-strewn industrial city and rail hub of Dnepropetrovsk, late in January, on a Heinkel bomber. Speer left—he thought it was safer—on a crowded hospital train. Todt would not oversee much more. He died on February 8 in the crash of a passenger-converted Heinkel III. Speer would be Todt’s successor.

THE WEEKLY ISSUE of

Time

dated December 27, in the mail or already delivered, described how the American West was responding to the war, with the Pacific Coast newly “conscious of its own immensity.” A column reported “a hand-scrawled sign on the fence post of a cross-roads farm: come in for coffee and cake. There were any number of signs like it.... Soldiers stationed nearby, passing along the gravel roads, miles from nowhere in the middle of winter, saw them even when they could not stop.... In the West, where the war seemed nearer, where the whole region was a military area and where, outside the cities, the line between the soldiers and the people dissolved and all but disappeared in the countryside of scattered farms, small towns, big trees and rain.” Concerned that the Japanese who struck Pearl Harbor might come back, “At forest-fire lookout towers, in little tarpaper-covered shacks scattered in hills along the coast, spotters watched the grey skies, 24 hours a day, 24 hours a day, in three-hour shifts.... On Whidbey Island in Puget Sound, on the channel in Bremerton, farmers kept watch all night on volunteer beach patrols, moved into shacks when the wind blew down their tents, tending cows when not on patrol.”