Paul Revere's Ride (11 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

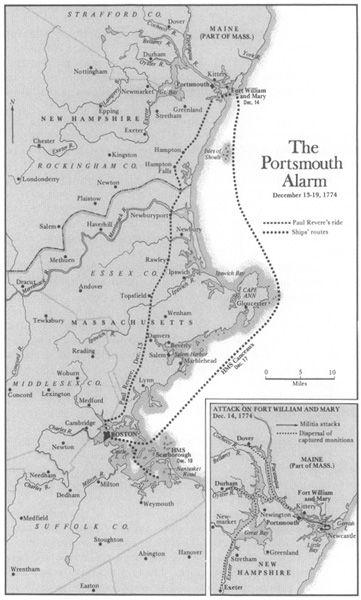

This time the Whigs of New England were on their guard. Paul Revere’s clandestine network functioned with high efficiency, and caught wind of the new British policy. Once again, Revere himself played a pivotal role. With various reports in hand, he and his friends decided to warn the people of New Hampshire that a large British expedition was ordered to Fort William and Mary, and possibly underway.

23

The date was December 12, 1774. British warships were indeed at sea along the coast of New England in severe winter

weather, and were thought to be heading for New Hampshire. Among them was

HMS Somerset,

a ship of the line with a large force of British Marines on board. In the latitude of Portsmouth, she met a fierce snowstorm that churned the coastal waters of New England into a seamen’s hell. A gale howled through her rigging, and foaming torrents of green water cascaded from her plunging bows. She was forced to heave to, her sails “close-reefed and banded,” with hand pumps “constantly going throughout the ship,” to keep her from sinking.

24

The Green Dragon Tavern was a massive brick building on the west side of Union Street. Modeled on another Green Dragon Tavern in Bishopsgate, London, it was operating in Boston as early as 1712, and became a center of revolutionary activity. The building was bought by Revere’s Masonic Lodge, hence the square and compass in the corner. The vehicle is a one-horse chaise such as Paul Revere himself used on at least one of his revolutionary rides. This ink and watercolor drawing by John Johnson in 1773 is in the American Antiquarian Society.

Admiral Graves wrote later, “This sort of storm is so severe it cannot be looked against, and by the snow freezing as fast as it falls, baffles all resistance—for the blocks become choked, the tackle encrusted, the ropes and sails quite congealed, and the whole ship freezes upon whatever part it falls and soon covers

the forepart of a ship with ice.” One may imagine the misery of her crew as they worked the frozen sails against the gale that was blowing in their faces. They had to “pour boiling water upon the tacks and sheets and with clubs and bats beat off the ice, before the cordage can be rendered flexible.”

25

Meanwhile, early in the morning of December 13, Paul Revere saddled his horse and hurried north to warn the people of Portsmouth. It proved to be one of his most difficult rides. Winter had come early to New Hampshire in 1774. The snow was deep on the ground by Thanksgiving Day, November 24. Another snow fell on December 9, and turned the highways into morasses of mud and slush. Then, in a typical New England sequence, the weather turned bitter cold. The thick slush froze in rough furrows on the rutted roads.

26

It was the sort of day when weatherwise Yankee travelers bided their time by tavern hearths. But Paul Revere could not wait for the weather. Determined to win his race against the Regulars, he mounted his horse and rode sixty miles from Boston to Portsmouth, under dark December skies. A piercing west wind howled across the dangerous highway, and chilled him to the bone.

Revere reached Portsmouth on the afternoon of December 13, 1774, and went straight to the waterfront house of Whig merchant Samuel Cutts. Portsmouth’s Committee of Correspondence quickly convened, and Revere reported his news. He told the Portsmouth Whigs that two regiments of Regulars were coming to seize the powder at Fort William and Mary. Further, he warned them that the King had issued an Order in Council prohibiting export of munitions to the colonies, and that new supplies would not be easy to obtain.

27

While the Whigs of Portsmouth were pondering this news, a Tory townsman reported Paul Revere’s arrival to New Hampshire’s Royal Governor John Wentworth, a man of energy and decision. Wentworth instantly alerted the small garrison at the fort, and dispatched an express rider to General Gage and Admiral Graves with an urgent request for help.

28

In fact, Paul Revere’s intelligence was not entirely correct. No British expedition had yet sailed for Portsmouth. HMS

Somerset

was merely in passage from Britain to America, and her Marines were part of the battalion promised to General Gage. But when Wentworth’s message arrived in Boston, Admiral Graves ordered a small sloop, HMS

Canceaux,

to depart immediately for Portsmouth with another detachment of Marines on board. A larger frigate, HMS

Scarborough,

was ordered to follow as soon as she could get under way.

Meanwhile, the New Hampshire men were acting quickly on the information that Paul Revere had brought them. Early on the morning of December 14, a fife and drum paraded through the streets of Portsmouth. By noon, 400 militiamen mustered in the town. They collected a fleet of small boats, and prepared to assault the fort. At about 3 o’clock in the afternoon the attack began, under cover of a snow storm. Some of the New Hampshire men marched overland to the fort. Others approached it by sea, paddling down the Piscataqua River in the eery silence of the falling snow, as clouds of white flakes swirled around them.

29

The garrison of British invalids saw them coming through the snow, and prepared to resist. The attackers demanded the surrender of the fort. Captain Cochran told them “on their peril not to enter. They replied they would.” The British garrison, outnumbered 400 to 6, bravely hoisted the King’s colors, manned the ramparts and managed to fire three four-pounders before the New Hampshire men swarmed over the walls from every side. Even then, the gallant British garrison continued fighting with small arms until they were overpowered by weight of numbers. The fort commander, Captain Cochran, surrendered his sword but was allowed to keep it. The New Hampshire men gave three cheers, and then to the horror of the garrison hauled down the King’s colors. Captain Cochran drew his sword that had just been returned to him, and was wounded and “pinioned” by the New Hampshiremen. Another of the British Regulars bravely tried to stop them. A Yankee snapped a pistol in the soldier’s face, then knocked him down with the butt end of it. These were truly the first blows of the American Revolution, four months before the battles of Lexington and Concord.

30

The New Hampshiremen took possession of the fort and broke open the magazine. They carried away more than 100 barrels of gunpowder by boat to the town of Durham, and then by cart to hiding places in the interior.

31

While the fight was going on, couriers were spreading Paul Revere’s message through the country towns of New Hampshire. By morning, more than a thousand men marched on Portsmouth. It was reported that “the men who came down are those of the best property and note in the province.” They returned to the fort and took away a supply of muskets and sixteen cannon, leaving about twenty heavy pieces behind.

32

The British reinforcements were too late. HMS

Canceaux

did not sail from Boston until December 17. She had a favoring wind, and managed to reach Portsmouth without incident. But when she arrived, a cunning Yankee pilot conned her into shallow water at high tide, and the British warship found herself helplessly “be-nipped” behind a shoal, unable to move for days. Admiral Graves, a rough unpolished sea officer with a furious temper, was reduced to a state of apoplectic rage.

HMS

Scarborough

was unable to get under way until December 19. As she left harbor the fickle Boston wind veered from the west to the northeast, and the weather turned so threatening that she was forced to anchor in Nantasket Road south of Boston until the wind changed. The storm-beaten frigate did not arrive in Portsmouth until a week after the attack on the fort. The New Hampshiremen had long since released their prisoners and melted away into the countryside. Paul Revere trotted back to Boston, his mission completed. The British commander of the expedition came ashore to find an infuriated Royal governor, a defeated garrison, a looted fort, and a hostile population.

33

For General Gage, the Portsmouth Alarm was a heavy defeat. The people of New Hampshire had been needlessly provoked to commit an overt act of armed rebellion. They had attacked the King’s troops, seized a large supply of powder, and carried it beyond the reach of British arms. Other towns throughout New England had acted in the same way. In Newport, Providence, and New London, cannon and munitions had been removed from forts and hidden in the interior.

34

The British leaders had no doubt as to the identity of the man who had brought about their humiliation. They attributed their defeat directly to Paul Revere. In New Hampshire, Governor Wentworth wrote that the trouble began with “Mr. Revere and the dispatch he brought with him, before which all was perfectly quiet and peaceable in the place.”

35

Paul Revere’s role was well known to British leaders in Boston. Within a few days of the event, Lord Percy wrote home, “Tuesday last Mr. Paul Revere (a person who is employed by the Committee of Correspondence, here, as a messenger) arrived at Portsmouth with a letter from the committee here to those of that place, on receipt of which, circular letters were wrote to all the neighboring towns; and an armed body of 400 or 500 men marched the next day into the town of Portsmouth.”

36

Many British officers wondered why General Gage did not

arrest a man who so openly defied him. Some would cheerfully have clapped him in irons, and left him to rot in a damp dungeon at Castle William in Boston harbor. But Thomas Gage believed strictly in the rule of law. The Whig leaders, Revere among them, were allowed to remain at liberty while frustrated British soldiers cursed their commander and their Yankee tormentors in equal measure. Even Gage’s lieutenant Lord Percy, outwardly loyal to his chief, wrote privately, “The general’s great lenity and moderation serve only to make them more daring and insolent.”

37

In February, Gage’s staff began to plan another stroke. A large supply of munitions was thought to be accumulating in the seaport town of Salem, the “shire town” for Essex County in the northeast corner of Massachusetts. Reports reached the British commander that many old ships’ cannon were being converted into field pieces at a Salem forge, and that eight new brass guns had been imported from abroad. General Gage decided to go after them.

38

Command of the mission was given to Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Leslie, an able and experienced officer, known for his moderation and restraint. Loyalist Ann Hulton described Leslie as “amiable and good … of a noble Scotch family but distinguished more by his humanity and affability.” Here was a man that Gage could trust.

Again the British commander in chief moved with his habitual caution and secrecy. Thomas Hutchinson Junior wrote of this expedition, “The general is so very secret in all his motions that his aide de camp knew nothing of this till it was put in execution.”

39

Elaborate precautions were taken to prevent detection by Paul Revere and his mechanics. For security, the mission was assigned to the 64th Foot, quartered on Castle Island in the harbor. These men were ordered to travel by sea directly from the island in the dark of night, so that nobody would see them depart.

40