Paul Revere's Ride (10 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

Early the next morning, September 2, 1774, McNeil set out for Boston. Afterward he wrote that “he never saw such a scene before. All along [the road] were armed men rushing forward— some on foot, some on horseback. At every house women and children [were] making cartridges, running bullets, making wallets [pouches of food], baking biscuits, crying and bemoaning and at the same time animating their husbands and sons to fight for their liberties, though not knowing whether they should ever see them again. … They left scarcely half a dozen men in a town, unless old and decrepit, and in one town the landlord told him that himself was the only man left.”

6

Ezra Stiles, a Congregationalist clergyman with a passion for statistics, estimated that “perhaps more than one third the effective men in all New England took arms and were on actual march for Boston.” Another observer reported that 20,000 men marched from the Connecticut Valley alone, “in one body armed and equipped,” and were halfway to Boston before they were called back.

7

William Brattle’s letter to General Gage somehow fell into Whig hands and was given to the newspapers. When the people of New England discovered what had happened, anxiety and fear gave way to unbridled fury. The rage of an entire region fell on a few Tories who happened to be within reach. Whig leaders who had been trying to awaken a spirit of resistance suddenly found themselves trying, in Joseph Warren’s words, “to prevent the people from coming to immediate acts of violence.”

8

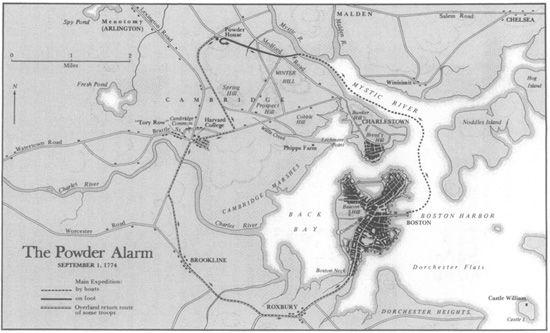

On the morning of September 2, a huge crowd of 4,000 angry men gathered on Cambridge Common, mostly farmers from the towns between Sudbury and Boston. Whig leaders persuaded them to leave their firearms in Watertown. Armed only with wooden cudgels, they marched to “Tory Row” in Cambridge, and gathered around William Brattle’s mansion. This elegant house had been his family’s seat through four generations. Its gardens and private mall extended all the way to the Charles River. The property itself was protected by Whig leaders, but Brattle was forced to flee for his life, and took refuge at Castle William in Boston harbor. He sent a pathetic letter to the newspapers: “My banishment from my house, the place of my nativity,” he wrote, “my house being searched though I am informed it was without damage, grieves me deeply … I am extremely sorry for what has taken place; I hope I may be forgiven.” But he was not forgiven. William Brattle was never allowed to go home again. He was a fugitive for the rest of his days.

The mob went on to visit Colonel David Phips, the Tory sheriff who had delivered the keys of the powderhouse, and compelled him to swear in writing that he would never enforce the Coercive Acts and would recall every writ issued “under the new establishment.” Another inhabitant of Tory Row, Thomas Oliver, was made to resign his seat on Gage’s new Royal Council. He wrote on a slip of paper, “My house at Cambridge being surrounded by about four thousand people, in compliance with their command I sign my name.”

9

It was a fiercely hot day, and tempers rose with the thermometer. The crowd moved to the house of Tory barrister Jonathan Sewall, and things got out of hand. Someone inside the Sewall mansion fired a pistol. An unruly mob of boys and servants smashed the windows and threatened to pull down the entire building. While Whig leaders held the crowd at bay, Jonathan Sewall fled to Boston. A few months later he left the country, never to return. Printed papers were nailed to the doors of Sewall’s fellow

lawyers, threatening death to any member of the Bar who appeared in the new courts created by the Coercive Acts.

10

Some of the mob, who were mounted, came upon Customs Commissioner Benjamin Hallowell in his opulent “post-chaise,” escorted by a servant in livery. A countryman came up to him and cried, “Damn you, how do you like us now, you Tory son of a bitch?” Hallowell took his servant’s horse and galloped toward Boston with a pistol in his hand, pursued by a howling mob of infuriated Yankees, said to number 160 mounted men and horses. Behind the thundering mob galloped three frantic Whig leaders, hoping to prevent bloodshed. As Hallowell approached the British sentries at Boston Neck, his horse collapsed. With the mob in full cry close behind him he sprinted to the safety of the British lines.

When the danger of violence passed, Boston Whigs rejoiced in the dramatic turn of events and spread the news to other colonies. Paul Revere, unable to travel himself, dispatched riders bearing his personal letters to leaders in other colonies. To his good friend John Lamb, a leading Whig in New York, Revere wrote triumphantly,

Dear Sir,

I embrace this oppertunity to inform you, that we are in Spirits, tho’ in a garrison; the Spirit of Liberty never was higher than at present, the troops have the horrors amazingly. By reason of some late movements of our friends in the Country, our new fangled Councellors are resigning their places every day; our Justices of the courts, who now hold their commissions during the pleasure of his Majesty, or the Governor, cannot git a jury to act with them, in short the Tories are giving way everywhere in our Province.

11

It is interesting to observe that Paul Revere’s thinking centered on “the Spirit of Liberty,” at a time when Thomas Gage thought mainly about material aspects of the problem. While Imperial leaders were laboring to remove the physical means of resistance, New England Whigs were promoting the spiritual will to resist. The two parties to this great conflict were not merely thinking different things; they were thinking differently.

General Gage was amazed by the rising of the countryside against him, and astounded by the anger he had awakened in New England. Instantly his mood changed, and suddenly he turned very cautious. His staff had already been planning another mission to seize munitions in Worcester, forty miles inland. This second strike was postponed, and later abandoned altogether.

The British commander began to think defensively. He ordered the town of Boston to be closed and fortified. Heavy cannon were emplaced on Roxbury Neck, in fear that the “country people” might storm the town. The inhabitants were ordered to surrender their weapons, lest they rise against the garrison. Stocks of powder and arms in the possession of merchants were forcibly purchased by the Crown.

12

After the powder alarm, this hastily printed handbill was tacked on the doors of Massachusetts lawyers, of whom many were Tories. (Public Record Office)

As commander in chief for America, Gage did what he could to concentrate his forces in Boston. But by late October he had only 3000 Regulars in the town, not nearly enough to control a province that had mustered ten times as many men against him in a single day. The first hints of winter were beginning to be felt in the crisp New England air, and the season for campaigning was nearly at an end.

13

General Gage began to send home dispatches that differed very much from his strong advice of the past five years. In the weeks after the Powder Alarm, he informed London that “the whole country was in arms and in motion.” He reported that “from present appearances there is no prospect of putting the late acts in force, but by first making a conquest of the New-England provinces.”

14

In November Gage went further, and urged that the Coercive Acts (which he himself had proposed) should be suspended until more troops could be sent to Boston. This idea caused consternation in London. The King himself angrily rejected Gage’s advice as “the most absurd that can be suggested.”

15

At the same time, Gage begged his superiors for massive reinforcement.

To Barrington he wrote, “If you think ten thousand men sufficient, send twenty; if one million is thought enough, give two; you save both blood and treasure in the end.”

16

In London those numbers were thought to be absurd, even hysterical. At the moment when Gage was asking for 20,000 reinforcements, only 12,000 regular infantry existed in all of Britain.

17

The King’s ministers replied that “such a force cannot be collected without augmenting our army to a war establishment.” Gage was sent a battalion of 400 Marines, and told to get on with the job.

18

Meanwhile, the Whig leaders of New England were gathering their own resources with greater success. A convention met in Worcester on September 21, 1774, and urged town meetings to organize special companies of minutemen, so that one-third of the militia would be in constant readiness to march. It recommended that a system of alarms and express riders be organized throughout the colony. In October, the former legislature of Massachusetts met in defiance of Governor Gage, and declared itself to be the First Provincial Congress. It created a Committee of Safety and a Committee of Supplies, modeled after the institutions of England’s Puritan Revolution and armed with executive powers.

The people of New England vowed never again to be taken by surprise. In Boston, Paul Revere went instantly to work on that particular problem. His chosen instrument was a favorite device in Boston: the voluntary association. Many years later he recalled that “in the Fall of 1774 and Winter of 1775 I was one of upwards of thirty, chiefly mechanics, who formed ourselves into a committee for the purpose of watching the movements of the British soldiers, and gaining every intelligence of the movements of the Tories. We held our meetings at the Green Dragon Tavern.”

19

Paul Revere himself was the leader of this clandestine organization. Its activities were shrouded in the deepest secrecy. He wrote, “We were so careful that our meetings should be kept secret, that every time we met, every person swore upon the Bible that he would not discover any of our transactions but to Messrs Hancock, Adams, Doctors Warren, Church and one or two more.”

20

Despite these precautions, General Gage quickly learned about this secret society. His source was Dr. Benjamin Church, who sat in the highest councils of the Whig movement, and betrayed it for money. The Whigs of Boston were soon painfully aware that Gage knew what they were doing. Many years later, Paul Revere remembered that “a gentleman who had connections

with the Tory party, but was a Whig at heart, acquainted me that our meetings were discovered, and mentioned the identical words that were spoken among us the night before.” Paul Revere’s mechanics were unable to discover who was betraying them, and began to suspect one another. All the while they continued to report their activities to Dr. Benjamin Church, never imagining that Church himself was the traitor.

21

Even as General Gage knew what Paul Revere and his friends were doing, he made no attempt to stop them. Perhaps he saw no reason to try, as long as Doctor Church was keeping him so well informed. Without interference, the Boston mechanics met at the Green Dragon Tavern, and organized themselves into regular watches. “We frequently took turns, two by two,” Revere remembered, “to watch the soldiers by patrolling the streets all night.”

22

In our mind’s eye, we might see them in the pale glow of Boston’s new street lights, patrolling the icy streets on long winter nights, their hands tucked under arms for warmth, and the collars of their short mechanics’ jackets turned high against the bitter Boston wind. All the while General Gage’s officers watched the watchmen through frosted window panes, then gathered around white oak fires in cozy winter quarters, and laughed knowingly into their steaming mugs of mulled Madeira.

Early in December, 1774, the British command recovered its nerve, and decided to strike again. An Order in Council prohibited the export of arms and ammunition to America, and ordered Imperial officials to stop “the importation thereof into any part of North America,” and to secure the munitions that were already in the colonies. Particularly at risk was a large supply of gunpowder, cannon, and small arms in New Hampshire. It was kept at Fort William and Mary, near the entrance to Portsmouth harbor, fifty miles north of Boston. The ramshackle fortress was garrisoned only by six invalid British soldiers, and vulnerable to attack.