Panic in Level 4: Cannibals, Killer Viruses, and Other Journeys to the Edge of Science (9 page)

Read Panic in Level 4: Cannibals, Killer Viruses, and Other Journeys to the Edge of Science Online

Authors: Richard Preston

Tags: #Richard Preston

Meanwhile, supercomputer system operators had become leery of Gregory. They worried that he might really toast a $30 million supercomputer. The work of calculating pi was also very expensive for the Chudnovskys. They had to rent time on the Cray. This cost the Chudnovskys $750 an hour. At that rate, a single night of driving the Cray into pi could easily cost the Chudnovskys close to ten thousand dollars. The money came from the National Science Foundation. Eventually the brothers concluded that it would be cheaper to build their own supercomputer in Gregory’s apartment. They could crash their machine all they wanted in privacy at home, while they opened doors in the house of numbers.

When I first met them, the brothers had got an idea that they would compute pi to two billion digits with their new machine. They would try to almost double their old world record and leave the Japanese team and their sleek Hitachi burning in a gulch, as it were. They thought that testing their new supercomputer with a massive amount of pi would put a terrible strain on their machine. If the machine survived, it would prove its worth and power. Provided the machine didn’t strangle on digits, they planned to search the huge resulting string of pi for signs of hidden order. In the end, if what the Chudnovsky brothers ended up seeing in pi was a message from God, the brothers weren’t sure what God was trying to say.

G

REGORY SAID

, “Our knowledge of pi was barely in the millions of digits—”

“We need many billions of digits,” David said. “Even a billion digits is a drop in the bucket. Would you like a Coca-Cola?” He went into the kitchen, and there was a horrible crash. “Never mind, I broke a glass,” he called. “Look, it’s not a problem.” He came out of the kitchen carrying a glass of Coca-Cola on a tray, with a paper napkin under the glass, and as he handed it to me he urged me to hold it tightly, because a Coca-Cola spilled into—He didn’t want to think about it; it would set back the project by months. He said, “Galileo had to build his telescope—”

“Because he couldn’t afford the Dutch model,” Gregory said.

“And we have to build our machine, because we have—”

“No money,” Gregory said. “When people let us use their supercomputer, it’s always done as a kindness.” He grinned and pinched his finger and thumb together. “They say, ‘You can use it as long as nobody

complains.

’”

I asked the brothers when they planned to build their supercomputer.

They burst out laughing. “You are sitting inside it!” David roared.

“Tell us how a supercomputer should look,” Gregory said.

I started to describe a Cray to the brothers.

David turned to his brother and said, “The interviewer answers our questions. It’s Pirandello! The interviewer becomes a person in the story.” David turned to me and said, “The problem is, you should change your thinking. If I were to put inside this Cray a chopped-meat machine, you wouldn’t know it was a meat chopper.”

“Unless you saw chopped meat coming out of it. Then you’d suspect it wasn’t a Cray,” Gregory said, and the brothers cackled.

“In a few years, a Cray will fit in your pocket,” David said.

Supercomputers are evolving incredibly fast. The definition of a supercomputer is simply this: one of the fastest and most powerful computers in the world, for its time. M zero was not the only ultra-powerful silicon engine to gleam in the Chudnovskys’ designs. They had fielded a supercomputer named Little Fermat, which they had designed with Monty Denneau, a supercomputer architect at IBM, and Saed Younis, a graduate student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Little Fermat was seven feet tall. It sat in a lab at MIT, where it considered numbers.

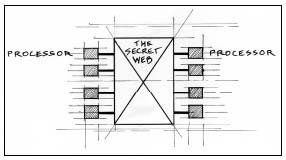

What m zero consisted of was a group of high-speed processors linked by cables (which covered the floor of the room). The cables formed a network among the processors that the Chudnovskys called a web. On a piece of paper, Gregory sketched the layout of the machine. He drew a box and put an X through it, to show the web, or network. Then he attached some processors to the web.

The design of the supercomputer m zero.

Drawing by Richard Preston

The exact design of this web was a secret. “Each processor is connected to all the others,” Gregory said. “It’s like a telephone network—everybody is talking to everybody else.” This made the machine very fast. They planned to have 256 processors. “We will be able to fit them into the apartment,” Gregory said. The brothers wrote the machine’s software in

FORTRAN

, a programming language that is “a dinosaur from the late fifties,” Gregory said, adding, “There is always new life in this dinosaur.” He said that it was very hard to know what exactly was happening inside the machine when it was running. It seemed to have a life of its own.

The brothers would not disclose the exact shape of the network inside their machine. The design contained several new discoveries in number theory, which the Chudnovskys hadn’t published. They claimed that they needed to protect their competitive edge in the worldwide race to develop ultrafast computers. “Anyone with a hundred million dollars and brains could be our competitor,” David said dryly.

One day, I called Paul Messina, a Caltech scientist and leading supercomputer designer, to get his opinion of the Chudnovsky brothers. It turned out that Messina hadn’t heard of them. As for their claim to have built a true supercomputer out of mail-order parts for around seventy thousand dollars, he flatly believed it. “It can be done, definitely,” Messina said. “Of course, that’s just the cost of the components. The Chudnovskys are counting very little of their human time.”

Yasumasa Kanada, the brothers’ pi rival at Tokyo University, was using a Hitachi supercomputer that burned close to half a million watts when it was running—half a megawatt, practically enough power to drive an electric furnace in a steel mill. The Chudnovskys were particularly hoping to show that their machine was as powerful as the Hitachi.

“Pi is the best stress test for a computer,” David said.

“We also want to find out what makes pi different from other numbers. Eh, it’s a business,” Gregory said.

David pulled his Mini Maglite flashlight out of his pocket and shone it into a bookshelf, rooted through some file folders, and handed me a color photograph of pi. “This is a pi-scape,” he said.

The photograph showed a mountain range in cyberspace: bony peaks and ridges cut by valleys. The mountains and valleys were splashed with colors—yellow, green, orange, violet, and blue. It was the first eight million digits of pi, mapped as a fractal landscape by an IBM supercomputer at Yorktown Heights, which Gregory had programmed from his bed. Apart from its vivid colors, pi looks like the Himalayas.

Gregory thought that the mountains of pi seemed to contain, possibly, a hidden structure. “I see something systematic in this landscape,” he said. “It may be just an attempt by the brain to translate some random visual pattern into order.” But as he gazed into the nature beyond nature, he wondered if he stood close to a revelation about the circle and its diameter. “Any very high hill in this picture, or any flat plateau, or deep valley would be a sign of

something

in pi,” he said. “There seem to be, perhaps, slight variations from randomness in this landscape. There are, perhaps, fewer peaks and valleys than you would expect if pi were truly random, and the peaks and valleys tend to stay high or low a little longer than you’d expect.” In a manner of speaking, the mountains of pi looked to him as if they’d been molded by the hand of the Nameless One,

Deus absconditus

(the hidden God). Yet he couldn’t really express in words what he thought he saw. To his great frustration, he couldn’t express it in the language of mathematics, either. “Exploring pi is like exploring the universe,” David remarked.

“It’s more like exploring underwater,” Gregory said. “You are in the mud, and everything looks the same. You need a flashlight to see anything. Our computer is a flashlight.”

David said, “Gregory—I think, really—you are getting tired.”

A fax machine in a corner beeped and emitted paper. It was a message from a hardware dealer in Atlanta. David tore off the paper and stared at it. “They didn’t ship it! I’m going to kill them! This is a service economy. Of course, you know what that means—the service is terrible.”

“We collect price quotes by fax,” Gregory said.

“It’s a horrible thing. Window-shopping in computerland. We can’t buy everything—”

“Because everything won’t

exist,

” Gregory broke in, and cackled.

“We only want to build a machine to compute a few transcendental numbers—”

“Because we are not licensed for transcendental meditation,” Gregory said.

“Look, we are getting nutty,” David said.

“We are not the only ones,” Gregory said. “We are getting an average of one letter a month from someone or other who is trying to prove Fermat’s Last Theorem.”

I asked the brothers if they had published any of their digits of pi in a book.

Gregory said that he didn’t know how many trees you would have to grind up to publish a billion digits of pi in a book. The brothers’ pi had been published on fifteen hundred microfiche cards stored somewhere in Gregory’s apartment. The cards held three hundred thousand pages of data, a slug of information much bigger than the

Encyclopaedia Britannica

and containing but one entry, “Pi.” David offered to find the cards for me. They had to be around here somewhere. He switched on the lights in the hallway and began rifling through boxes. Gregory got up and began fishing through bookshelves.

“Please sit down, Gregory,” David said. Finally the brothers confessed that they had temporarily lost their billion digits of pi. “Look, it’s not a problem,” David said. “We keep it in different places.” He reached inside m zero and pulled out a metal box. It was a naked hard drive, studded with chips. He handed me the object. It hummed gently. “There’s pi stored on it. You are holding some pi in your hand.”

M

ONTHS PASSED

before I visited the Chudnovskys again. They had been tinkering with their machine and getting it ready to go after two billion digits of pi when Gregory developed an abnormality related to one of his kidneys. He went to the hospital and had some

CAT

scans made of his torso, to see what things looked like in there. The brothers were disappointed in the quality of the pictures, and they persuaded the doctors to give them the

CAT

scan data. They processed it in m zero and got detailed color images of Gregory’s insides, far more detailed than any image from a

CAT

scanner. Gregory wrote the imaging software; it took him a few weeks. “There’s a lot of interesting mathematics in the problem of making an image of a body,” he remarked. It delayed the brothers’ probe into the Ludolphian number.

Spring arrived, and Federal Express was active at the Chudnovskys’ building, while the superintendent remained in the dark about what was going on. The brothers began to calculate pi. Slowly at first, then faster and faster. In May, the weather warmed up and Con Edison betrayed the brothers. A heat wave caused a brownout in New York City, and as it struck, m zero automatically shut down and died. Afterward, the brothers couldn’t get electricity running properly through the machine. They spent two weeks restarting it, piece by piece.

Then, on Memorial Day weekend, as the calculation was beginning to progress, Malka Benjaminovna suffered a heart attack. Gregory was alone with his mother in the apartment. He gave her chest compressions and breathed air into her lungs, although later David couldn’t understand how his brother hadn’t killed himself saving her. An ambulance rushed her to St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital. The brothers were terrified that they would lose her, and the strain almost killed David. One day, he fainted in his mother’s hospital room and threw up blood. He had developed a bleeding ulcer. “Look, it’s not a problem,” he said to me. After Malka Benjaminovna had been moved out of intensive care, Gregory rented a laptop computer, plugged it into a telephone line in her hospital room, and talked to m zero over the Internet, driving his supercomputer toward pi and watching his mother’s blood pressure at the same time.

Malka Benjaminovna improved slowly. When she got home from the hospital, the brothers settled her back in her room in Gregory’s apartment and hired a nurse to look after her. I visited them shortly after that, on a hot day in early summer. David answered the door. There were blue half circles under his eyes, and he had lost weight. He smiled weakly and greeted me by saying, “I believe it was Oliver Heaviside, the English physicist, who once said, ‘In order to know soup, it is not necessary to climb into a pot and be boiled.’ But look, my dear fellow, if you want to be boiled you are welcome to come in.” He led me down the dark hallway. Malka Benjaminovna was asleep in her bedroom, and the nurse was sitting beside her. Her room was lined with her late husband Volf’s bookshelves, and they were packed with paper. It was an overflow repository.