Oxfordshire Folktales (9 page)

Read Oxfordshire Folktales Online

Authors: Kevan Manwaring

A scholar was out walking in Shotover Forest, to the north of Oxford in the region known as Otmoor – a marshland notorious for rum doings. He was deep in philosophical reverie, considering a tome by Aristotle, when he was suddenly assailed by a ferocious wild boar which charged him from the undergrowth, tusks flashing, shrill squeal splitting the air. Thinking on his feet, the scholar thrust the tome in his hands into the boar’s mouth, stopping it dead in its tracks, crying out:

‘Glaecum est!

’ (with compliments of the Greeks). The boar was overcome by this quick-thinking scholar and thus the savage was conquered by the sage.

And so, to commemorate this wild hog story, the Boar’s Head Feast is held every St Stephen’s Day.

Yet, its origins might date back even further, for in Norse tradition a sacrifice was made at midwinter to Freyr to ask for favour for the coming year. Freyr is known as Ingwi in Saxon, and associated with the rune Ingwaz, the rune of new beginnings, new opportunities and new life; and of peace and harmony – it seemed Peace on Earth and goodwill to all men was something even the Vikings valued at this time of year. In old Swedish art, St Stephen, whose feast day is, as we know, the 26th of December, is depicted tending horses and offering a boar at a Yuletide feast. In Sweden to this day, a fine leg of Christmas ham is a traditional addition to the family feast.

And so, there is a possibility that an ancient midwinter sacrifice to the Norse god Freyr is enacted every year in Queen’s College, Oxford – a notion to relish, but perhaps one that is best

ervitor cum sinapio

: served with mustard!

![]()

Here are the lyrics to the ancient Boar’s Head Carol

(one version of several):

The boar’s head in hand bear I

Bedecked with bay and rosemary

I pray you, my masters, be merry

Quot estis in convivio.

(However many are at the feast)

Chorus:

Caput apri defero,

Reddens laudes domino

.

(I bring the boar’s head,

giving praises to the Lord)

The boar’s head, as I understand,

Is the rarest dish in all this land,

Which thus bedecked with a gay garland

Let us

servire cantico

(serve with song)

Chorus

Our steward hath provided this

In honor of the King of bliss

Which, on this day to be served is

In

Reginensi atrio

(in the Queen’s hall)

Chorus

T

HE

D

RAGON

C

UP

The two armies lined up either side of the ice-cold river Brue; the banners of the white horse of Wessex and the black hound of Mercia faced each other above the arrow-heads of tents. They had been camped there, on the flood meadow, for many days. Food and firewood was in short supply and tempers were frayed. It was the dead of winter and it seemed hope had died also. The endless cold was making the men sharp-tongued and quick to violence. The warriors of Beorna were like bears with sore heads, surly and dangerous. They took to sharpening their weapons and polishing their armour.

They had come to Bernecestre to make a treaty – for it stood on the borderland between Mercia and Wessex. Two kingdoms at war, and caught in the middle – Beorna, the local chieftain, who gave his name to ‘the fort of the warriors of the Bear’. He had protected his people for many seasons; his great beard was peppered, his heavy brows bearing a slash of white scar across one side. He wore the bearskin of his totem – the mighty fur draped over his massive frame and covering his crown with a frozen snarl. He leant upon his favourite weapon, the two-handled battle-axe and spat into the mud of the Pingle – the no man’s land stretching across to the enemy camp. To step foot on it was an act of war. The armies were on tenterhooks, and looking for the slightest provocation not to sign the treaty. The peace treaty had taken many months of negotiation, largely by the white-cloaked priests – who prided themselves on being meek, humble peacemakers. At first these strange ‘men of the white’ were mocked by Beorna and his warriors – they were not

real

men. No steel by their thigh, only twigs, some jibed. Yet something about their humble persistence intrigued Beorna – after knowing decades of conflict he was weary.

Surely, there had to be another way?

In the centre of the Pingle there was a single oak tree. Its branches swirled in the wind, which howled around the armies that day, bringing with it biting hailstones, clattering onto the carts, hissing into the braziers, sending anything not secured flying: stools and tankards, shields and banners. There was a devil in the air, all the men agreed. Beorna growled at them, and his entourage fell silent. ‘Are you warriors, or women?’ he bellowed. ‘I need men today – for what we have to do takes strength and courage. Any fool can make war; but it takes a wise man to make peace.’

‘But the Mercians are scum!’ snarled one of his shieldmen. More murmurs of assent. ‘They have raided our lands for decades, raping our women, stealing our cattle, burning our villages. And you want us to make peace with them!’ Roars of indignation echoed around the mead-hall.

‘Yes! As the White Brothers say, if we do not forgive, how can we ever move on? How can things heal?’

Sounds of scepticism hissed like rain in the fire-pit.

‘It may seem strange to us,’ Beorna continued, ‘we are more used to letting our steel do the talking.’ The men laughed in self-congratulation. ‘But for once, men, think with the steel up here.’ He clonked his helm with his axe.

* * *

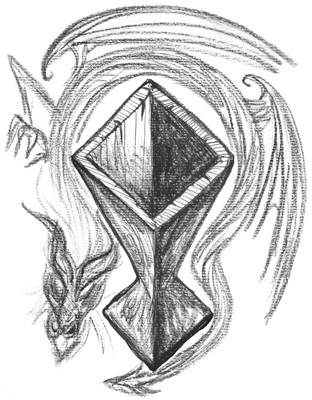

Beorna and his Royal Guard made their way to the ford and crossed the turbid waters to the Pingle, slipping on the muddy bank. They reached the oak at the same time as the iron-eyed Mercians. They eyed each other warily. In the shelter of the tree a table had been set up with scrolls, ink, quills and hot wax for sealing. On the table sat the Dragon Cup, used for oath-making for generations; it was an ancient wooden goblet that ‘once belonged to a great king.’ A serpent wound around its base, carved in exquisite detail, eating its own tail, wings extending to the chipped gold rim, worn smooth with the mouths of chieftains and champions who have supped from it, raising a toast to peace.

Testily, the two kings sat looking at each other across the table. The Danish king cast a cold eye over Beorna, the Wessex chieftain. He was renowned for his ferocity, and his ‘fort of the warriors of the bear’ was the thorn in Mercians side. The constant raiding and skirmishes along the borders was an expensive distraction. Like two wild siblings, Mercia and Wessex fought for the bigger territory, for the lion’s share – yet after decades of attrition both kings realised neither was gaining anything from this. It would be of mutual benefit to reach an accord – and that is why they had come, on this cold winter’s day. A fire guttered in the corner, the icy wind teasing the flaps of the tent. Around them, stern bodyguards watched on – the elite from both sides.

Before them was the Dragon Cup.

Mercia spoke first. ‘You’re bear-shirts raid our territories.’

Beorna considered this. ‘They merely claim back what is theirs – from lands you stole.’

The air crackled between them and the cup seemed to crack also, or was it just the fire spitting?

‘Stole, or won in victory? Surely Beorna acknowledges the right of the victor? This very cup is a spoils of war – it has been handed down through out bloodline for generations, yet here I see it before me.’

The cup cracked a little more.

‘Yet whose was it originally, my friend? Did not your ancestors seize it from a royal hoard, plundering the barrows of the dead?’

‘Lies! It was a gift from the gods – it was found by a pool one day, left by the Unseen Ones.’

This time the cup cracked in two. Both looked on, astonished. And then there was uproar. The meeting ended in disarray. The kings returned to their armies, where talk of an imminent battle rippled through the ranks. This would be a day not of peace, but of slaughter. There would be plenty for the crows to feed upon, come morning.

* * *

Then, at first light, as mist rose from the frosted ruts of the Pingle, a man in a white robe came, walking boldly between the armies, chanting something caught in snatches on the wind. Was he moon-touched? He walked towards the tent, now unguarded and empty, save for the fragments of the Dragon Cup. He went and emerged with them, holding the shattered shards aloft. Both armies looked on in grim silence. The air was tense. Who was this fool? A battle was about to take place – if he doesn’t get out of the way, he will taste steel.

‘Brave and mighty Kings of Mercia and Wessex. Brave and mighty warriors – hail and heed!’ Though he looked frail, he voice was clear as a mountain stream and carried across both camps, across the frozen land. ‘I hold the Dragon Cup – long has this sacred vessel bequeathed sovereignty on its owner, but look at its state. A symbol of this broken land. It is said when three untruths were spoken over it, it shall shatter – and you see the result.’

Warriors from Mercia growled: ‘You call our king a liar? We will tear that tongue from your head!’

Unflinching, the priest continued. ‘You both lay claim to this place, but who, ultimately, owns this land?’ He did not wait for an answer. ‘The one true God himself! His Spirit binds all, transcends all. Without it, we shall destroy each other until nothing is left. Only the love of Spirit maintains this Matter, the flesh of the Earth. And we are part of it.’ As the priest spoke, the cup started to mend itself. ‘Both kings have equal claim, and shall be equal stewards of this land. Long have their people lived here. Who owns the land? Any who work upon it, who worship upon it, who give their loyalty and love it.’ The cup mended some more. ‘Live together in peace – may you come here to trade goods and tales. Come drink the Dragon Cup and forge the sword of peace.’ The final fragment fell into place. The cup was mended. The priest held it aloft, to the gasps and murmurs of those gathered. ‘Three untruths break it; three truths mend it. I have spoken, and the spirit of the one true God is through me!’

The two kings came forward, with their royal bodyguards. They took turns to examine the cup and were impressed. The priest poured some wine into the cups ‘To Peace.’

Beorna slowly raised it and drank. Looking at his enemy with a level, penetrating gaze, he spoke the words like a challenge, daring him to defy them: ‘To Peace.’

Finally, the Mercian king did the same. ‘To Peace.’

The Bear-Chieftain addressed both armies. ‘A great miracle has been performed here this day. Let a temple be raised on this spot to house your spirit, and this cup. Let it be remembered, so none may forgot its healing magic.’

Time flows on. Kings and knaves turn to dust. But sometimes a trace of their lives remain. Beorna’s name endured; the place by the banks of the river Brue became known as the ‘fort of the warriors of the Bear’ – Bicester – and if you go to the church of St Edburg’s you’ll see, in two of the windows, the Dragon Cup.

![]()

This tale was inspired by the stained-glass windows in the ancient church of St Edburg, two of which depict the ‘Dragon Cup’. I used this motif in imagining a kind of ‘creation myth’ for Bicester, based upon the historical evidence of its earliest inhabitants. Sometimes a ‘story of place’ is enshrined in a name, when all other evidence has vanished – and so the ‘fort of the warriors of the bear’, or the ‘tribe of the warriors of Beorna’, seemed too enticing to turn down. The Pingle can still be seen, demarcating the lovely old town from the ‘designer village’ which has spawned on Bicester’s edge. Different forces besiege the town these days. What would Beorna think of it all?

The motif of the ‘four-squared cup of truth’ comes from Celtic tradition (I first came across it in John and Caitlin Matthews’ Celtic Wisdom Tarot).