Oxfordshire Folktales (11 page)

Read Oxfordshire Folktales Online

Authors: Kevan Manwaring

Old Bliss concluded his story to a round of applause.

‘What about the maidens and the cup of gold?’ asked Lucy.

‘My, you are a curious one, aren’t you!’ Laughter rippled around the glade. ‘Well, they seemed to vanish from the land, but now and again, if you’re lucky, you might catch a glimpse of one, offering a cup of kindness to a passing stranger.’ He winked at his audience. ‘Which reminds me…’ He smacked his lips. ‘Anyone have a drink for a thirsty teller?’

Hartlake, who had been listening to the tale with stern attention, suggested to the villagers they must share the Waters of Life, otherwise they might turn corrupt too! Scowling fondly at Old Bliss, the Reverend declared to his flock it was time to return. The villagers followed, and someone struck up a tune on a fiddle. An Easter Monday fair awaited them upon their return, tables laid out with fine food and drink. They had completed their rite of Spring and had made ‘Spanish Water’ – Holy Water.

Lucy savoured her bottle of sunlight, cool in her hands, and stored up the memories of the day: the bluebells; Hartlake’s sermon; Old Bliss’s tale; and the blessing of the wood – which was the best medicine of all. And you don’t need to go to Spain to enjoy that.

![]()

This story was inspired by the following fragment, which I found in Katherine Briggs’

The Folklore of the Cotswolds:

On Easter Monday the people of Leafield considered it their right to go to one of the forest springs to make ‘Spanish Water’. This was kept as a remedy for almost every disorder. On Easter Monday I have met troops of Leafield people going through the forest with their bottles to make Spanish Water.

Another source, June Lewis-Jones’

Folklore of the Cotswolds,

says this was done on Palm Sunday: ‘The reputedly miraculous spring water of Wychwood was mixed with Spanish liquorice and lemon to make a cure-all to last the entire year.’ Holy Water was deemed to be rainwater caught on Holy Days, such as Easter and the many saints’ days. This was particularly prized for bathing sore eyes in, as it was water which ‘ran against the sun’, that is from west to east. Other Spring customs persisted in the Wychwood area, suggesting that this was once a common folk practice – perhaps a remnant of the worship of water by the Celts.

A G

IFT

OF

W

ATER

The gift of life flows and should never be owned. Water is a miracle that makes life on Earth possible. It is a precious resource that links us all – without it we would perish. A clean glass of water is the same to a thirsty man, whatever nationality he is. Wherever on Earth we dwell, this universal water table connects us all; yet sometimes it wells up in unexpected places…

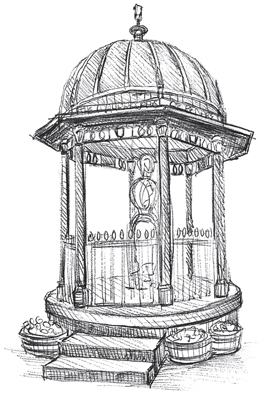

A village in the Chilterns is perhaps the last place you would expect to see a Maharajah’s well. To a thirsty traveller walking the Icknield Way – that ancient trackway running a couple of miles by Ipsden, as it was then – the well might appear like a mirage, yet it is real, found within the parish of Stoke Row. Sitting within its own small park, complete with a small cottage, it is a most splendid edifice – an onion-shaped dome covering the well-head, where winch apparatus is protected by a golden elephant like some Indian shrine. How did it come about?

It was the mid-nineteenth century and the Empire was in full swing. Half the world was painted pink and an Ipsden man was doing his bit for HIM (Her Imperial Majesty). Mr Edward Reade, the local squire, had worked with the Maharajah of Benares in India for many years. One of his many deeds there was to sink a well in 1831, to aid a local community in Azimurgh. He talked about how water was often a problem for villagers in his homeland – the chalk hills of the Chilterns – after a dry spell.

When Mr Reade finally left the area in 1860, he asked the Maharajah to ensure that the well remained available to the public.

A couple of years later, the Maharajah decided on an endowment in England. He recalled Mr Reade’s generosity in 1831 and also remembered his stories of water deprivation in his home area of Ipsden. It was surprising to hear of this: a drought … in England? And yet it made the seat of the Empire more human and endearing. Perhaps these ‘white lords’ weren’t invulnerable after all. The Maharajah’s compassion was piqued. And so the well in Stoke Row, as Ipsden became known, duly came about.

It was dug, by hand, all three hundred and sixty-eight feet of it, to a width of four feet. Greater than the height of St Paul’s Cathedral; more than twice the height of Nelson’s Column. It took about a year to build. Hard work, backbreaking work – yet it created local employment nonetheless.

The well and superstructure cost a princely sum of £353 13

s

7

d

. The elephant and machinery cost a further £39 10

s

, the project was undertaken by the local firm of Wilder in Wallingford, still to be found in the town. Finally, a cottage was raised for the modest cost of £74 14

s

6

d

. This was where the well-keeper would dwell, to maintain the Maharajah’s gift.

The well was opened officially on Queen Victoria’s birthday in 1864. The winch turned and the water flowed – a miracle from below!

The well remained in use for over seventy years – a lifetime – until pipes brought water to the village from reservoirs, and cottages started to acquire rudimentary plumbing. After that, it was used less and less, but has been preserved as a symbol of a special friendship spanning continents.

Wherever you live in the world, water is precious. Perhaps the Maharajah’s Well in Stoke Croft will help remind us of that, thanks to this noble gift.

![]()

Links with the Maharajah continue to the present day. When Queen Elizabeth II was visiting Benares (these days known as Varanasi) in 1961, the Maharajah pointed out that the well was shortly coming up to its centenary. He invited the Duke of Edinburgh to visit Stoke Row for the celebrations. This he duly did, arriving in his red helicopter – a detail preserved in the village newspaper, adorning the logo. A little corner of Oxfordshire is connected, through this remarkable monument, to the blue blood of two continents.

T

HE

S

NOW

F

ORESTERS

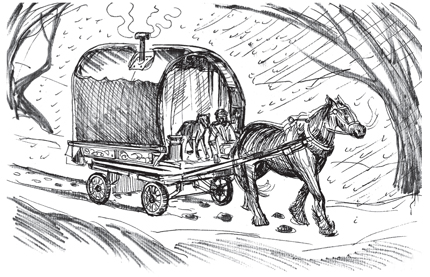

There’s an old saying: ‘Stow on the Wold, where the wind blows cold and the cooks have nothing to cook.’ And cold and hungry they were, those poor tinkers passing through the ghost-webbed groves of Wychwood that night. It was Christmas Eve and they were making their way across the ’Wolds from Burford to Stow. The gypsies, road-hardened as they were, were having a hard time of it – for it was blowing a blizzard and their best nag, Old Ness, struggled to pull their barrel-top caravan up the steep snow-bound lane towards the hill-top town. They were passing through a lonely stretch of road that ran by a wood outside Idbury – it was shunned by travelling folk for being haunted by the Snow Foresters – the un-peaceful dead. Can you not hear them screeching and scratching on the caravan window with their icy fingers? Inside, the family huddled together and out front Pa gritted his teeth and tugged on the reins harder. They had to find shelter, and soon!

The snow howled around them outside, as though it was alive with a malign intelligence, seeking out every gap. Their teeth chattered and their knees knocked together.

‘If Old Ness don’t hurry up, the Snow Foresters’ll get us,’ they wailed.

Suddenly, they heard another sound at the door – the boy heard it first. ‘There’s something out there!’

‘Sshhh, lad.’

‘No, listen – it’s a mewing! It’s a kit-cat. We can’t leave it out in the cold!’ He opened the door and a little white kitten came in, shivering, snowflakes melting on its fur.

‘Put it out!’ said the mother, for they believed such creatures were a death-token.

‘No Mam, it’s as lost as us and as little as me. Us can’t turn it out. Is it not Christmas Eve?’

‘Tis so,’ replied his Mam.

‘Then will speak to us, if we ask it in rhyme: Is it, Kit-Cat?’

The kitten replied, ‘Tis so!’

The family gasped.

Having their attention, it continued: ‘And you’ll all win safe through if ye can keep on to the church bells. Hearken to the birds a-twittering and follow after them – for they go to join in the carols at Stow.’

Well, when a cat speaks, even a little one, it’s worth listening to, and so this is what the family did.

‘Listen!’ said the son, who had ears keener than the rest.

Above the howling, the scritch-scratching and the tap-tapping, the gypsy family heard the sound of hundreds of little birds flying by.

The sound warmed their hearts, and gave them courage and a new strength to carry on – Old Ness ploughed on through the snow and they sung carols to keep their spirits up and keep the Snow Foresters at bay.

Finally, they came to lodge on the outskirts of Stow, and there a kindly farmer let them in for the night, for the sake of Christmas charity: and not a moment too soon. They were chilled to the bone but were soon thawing out around a cosy fire with something warming in a glass. They toasted the turning of the wheel of fortune. It had just passed the stroke of midnight, the Christmas bells were ringing and the snow had finally stopped, and the little white kit-cat was gone.

The little lad said. ‘I knew it! She wasn’t a witch’s cat. I think, I think … she was a little fallen angel that was earning her way back to Heaven.’

‘Ah,’ said Granny, thawing out by the fire. ‘Then that was another good deed for her.’

And the family thought on as they fell asleep, huddled cosily together by the hearth, what good deeds they had done that year to help them find their way back to the hearth of Heaven.

Perhaps they were all a little closer.

![]()