On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (44 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

The philosopher Daniel Dennett offers a provocative analogy for understanding the suicide bomber’s religious devotion, one that underscores the

inhuman

aspect of the influence of ideology. Certain kinds of parasites need to get into the stomach of a cow or sheep to successfully mature and complete their life cycle. To accomplish this relocation, the fluke enters some hapless ant and, by manipulating its navigation system, causes it to crawl to the top of a grass stalk. A cow comes along and eats the ant as part of its grass diet; the fluke has thus successfully entered the cow, using the ant as a vehicle. The ant obviously comes out of this process rather badly; it is simply manipulated by the parasite and loses its own chance for reproduction and longer life. Dennett points out that this whole manipulative process can be found in religious devotees: “We often find human beings setting aside their personal interests, their health, their chances to have children, and devoting their entire lives to furthering the interests of an

idea

that has lodged in their brains.”

52

Like any successful organism, religion seeks to promulgate itself (in this case, its memes rather than its genes), and it uses individual believers to make more of itself. For humanists like Dennett, religion is like a seething monstrous mother, pulsing in her lair and spilling out parasitic spores and tentacles to subdue host organisms.

One of the major reasons ideologies seem potentially dangerous, whether they are religious or social or economic, is because they occupy a space in human thinking that is highly influential but also unverifiable. In the religious case, idealistic beliefs are not just difficult to corroborate or check against experience, they are sometimes explicitly and proudly anti-empirical and antirational. God’s incomprehensibility, a monstrous magnitude, was examined in

chapter 12

in my discussion of the tradition of the sublime. Here in the contemporary critique of ideology and religion we have another rehearsal of the secular idea that going outside of reason and empirical proof leads one to monstrous territory. Just as the early cartographers announced on the uncharted sections of their maps “Here Be Monsters,” critics of ideology want to paint the same warning. Monstrosity is that which exists outside rational coherence. If zealots choose to embrace that monster, then monstrous consequences will follow.

53

All this illustrates a shift in the way we think about monsters. Instead of solitary freaks born of evil parentage or pathological genetics, we think of them as churned out by abstract alienating systems, social and ideological

machines that cannot feel the beating hearts inside them. This is one of the major themes of Franz Kafka’s stories and has become so commonplace a characterization of modern

organization

that we now refer to such crushing bureaucracies and philosophies as “Kafkaesque.” Modern organization alienates us from each other and from our own self, reducing our humanity and tilting us toward zombie status.

Social constructionism

is the name we give to a loose confederation of ideas about the artificial nature of human knowledge and, by extension, the constructed nature of reality itself. Previously, we thought of the categories species, race, and gender as

natural

, as concepts that pick out features of the real world. The real world was thought to be composed of distinct things and properties, and our languages and sciences were thought to capture those realities in a net of essence-defining descriptions. Social constructionism, on the other hand, suggests that such linguistic categories are more like social conventions, fabricated mostly by the powerful for the purpose of sustaining their power advantage. In recent years we have come to apply this same constructionist logic to everything. We have arrived at the moment in history (presaged dimly and occasionally in earlier ages) where we can say, “One is not born but rather becomes a monster.”

In our age of postmodernism (a radical form of social constructionism), it is a good time to be a monster. The monster is but another subspecies of the other, and like all marginalized, subordinated groups, the monster can finally let its hair down and glory in its

difference

. Postmodern theory seeks to deconstruct the dominant social constructions of normative boundaries and rewrite or rebuild them with losers as winners, walk-on extras as main characters, and deformed outcasts as principal luminaries. There is no grand narrative, no universal human nature, no objective reality, no Enlightenment truth to be captured by reason. The politics of difference, which issued from the denial of traditional norms, is a good milieu for monsters.

54

We saw in the modernization of Grendel and Beowulf how

evil demons

can be recast as

misunderstood victims

. But here, in the contemporary paradigm of postmodernism, the relativism of values seeps even deeper. Formerly we were interested in what makes a person

be

a monster; now we are more concerned with what makes a person

seem

a monster.

55

Relativism, at least in the social sciences and humanities of the academy, is the reigning monsterology of our day. There are no real monsters, only oppressive labels and epithets.

It is ironic that the current champions of neo-Enlightenment liberal values (Hitchens, Hirsi Ali, etc.) consider the superstition that lies

outside rationality

to be the monster, whereas the postmodern decon-structionists consider

rationality itself

to be a repressive and totalitarian monster, forcing everything into a procrustean fit. Fans of the theorist Jacques Derrida, the father of deconstructionism, have suggested a secret history of Western thought, a history of the outcast, including the ultimate philosophical “outcast”: the

nothing

, or negation. Reason seeks to map reality, but what about the obscure territories that fall outside of the map? These unreasonable gaps in knowledge have been waiting in the secret darkness of Western thought, occasionally peeking through in moments of skepticism and suspicion, waiting until the deconstruction-ists came along to unleash them into the machine of logos.

56

Individual monsters (Frankenstein’s creature, Jeffrey Dahmer, Dracula, the Blob, etc.) are violations of normal rational taxonomy, but also the general

idea

of the monster is, for deconstructionism, like a conceptual place-holder for all things unclassifiable and a celebration of the irrational.

57

Deconstructionism clears a path to new freedoms and diversity. When everyone is a monster, there will be no monsters.

Interestingly, as soon as the postmodern embracers of irreducible pluralism and diversity staked their ideal ground of a monsterless, otherless beatitude, their putative enemies, the rationalists, seemed to be growing horns, fangs, and tails. We cannot get rid of monsters, no matter how righteously tolerant we get.

My own sympathies, which are probably obvious by now, lie with the neo-Enlightenment liberals.

58

Yes, some monsters have turned out to be wrongfully accused and others have been conjured entirely by politicians and priests, but that doesn’t mean there is no such thing as monsters. The understandable desire to avoid the lamentable witch hunts of our history, both recent and ancient, has led many relativists to abandon the term and the concept of monster altogether, seeing it as an outmoded relic.

In 2006 in Kandahar, Afghanistan, four armed men broke into the home of an Afghan headmaster and teacher named Malim Abdul Habib.

59

The four men gathered Habib’s wife and children together, forcing them to watch as they stabbed Habib eight times and then decapitated him. Habib was the headmaster at Shaikh Mathi Baba high school, where he educated girls along with boys. The Taliban militants of the region, who are suspected in the beheading, see the education of girls as a violation of Islam, a view that is obviously not shared by the vast majority of Muslims. My point is simply this: If you can gather a man’s family at gunpoint and force them to watch as you cut off his head, you are a monster. You don’t

merely

seem

to be one, you

are

one. A relativist objection here sounds coldly disingenuous.

The relativist might finally counter by pointing out that American soldiers at Abu Ghraib tortured some innocent people, too. That, I agree, is true and astoundingly shameful, but it doesn’t prove there are no real monsters, it only widens the category and recognizes monsters on both sides of an issue. Two sides calling each other monsters doesn’t prove that there are no monsters. In the case of the American torturers at Abu Ghraib and the Taliban beheaders in Afghanistan, both epithets sound entirely accurate.

Future Monsters

Robots, Mutants, and Posthuman Cyborgs

MUTANTS AND ROBOTSIt’s obvious that every effort is being made in these years to replicate a human being and forge armies of them. It might take two centuries, but it does seem to be what we humans are hell-bent on doing

.

NORMAN MAILER

W

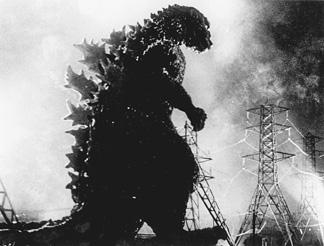

HEN GODZILLA MADE HIS FIRST FILM

appearance in 1954 he created a sensation and a whole new “giant monster” (

kaiju

) genre. Soon audiences would thrill to the likes of Mothra, Rodan, King Ghidorah, and Gamera. The original film

Godzilla

was actually considered to be high art in Japan, compared frequently with the great films of Akira Kurosawa.

1

American audiences experienced a recut version and a less compelling plot line. In the original film, Japanese fishing boats are mysteriously destroyed off the coast of Odo Island, and old legends about a monster god named Godzilla begin to circulate among the natives. Soon specialists and reporters are called in, and the gigantic creature rises out of the water to begin a rampage of local villages and eventually Tokyo itself. Scientists determine that the monster is actually an ancient dinosaur that has been revived and mutated by underwater atomic tests. Further investigation reveals that Godzilla is suffused with radiation, giving him almost immortal powers of resilience and a deadly atomic ray that he breathes like fire. After he passes through a city, the survivors of

his attack find themselves suffering from radiation poisoning. Dr. Daisuke Serizawa is the reluctant creator of a superweapon, called “the Oxygen Destroyer,” and he is enlisted to use the terrible device against Godzilla. Serizawa resists deploying the weapon on the grounds that, once such devastating power is witnessed, every government will pursue it to ruinous result for the whole planet. Finally he yields and personally dives into the sea with the weapon to exterminate Godzilla. As he successfully unleashes the weapon against the monster, he also cuts his own lifeline and dies with the only knowledge of the weapon, thereby preventing further exploitation of the odious invention.

Science and hubris once again give birth to monsters. Godzilla lays waste, in the original 1954 Japanese production of

Godzilla

(Toho Company, Ltd.). Image courtesy of Photofest.

This is a stunning plot when we consider that it was created only nine years after the real atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Moreover, in 1954 a Japanese fishing boat was exposed to massive radiation contamination by American testing on Bikini Island. The crew and the vessel,

Daigo Fukuryu Maru

(Lucky Dragon 5), were outside the supposed danger zone, but the blast was much bigger than expected, and the crew received deadly radiation poisoning. The film

Godzilla

entered popular culture at a moment when Japanese outrage against nuclear weapons was at

fever pitch, and the terrible tragedy of a mere decade before was still fresh in public consciousness.

This masochistic dimension of monster stories is already contained in

Frankenstein

and in the Christian and pagan traditions. Monsters, according to this logic, frequently come to take revenge on deserving individuals and even cultures. God or fate dispatches terrible creatures to dispense the wages of sin. Human arrogance is repaid by chaos and destruction. In some ways, the religious or cosmic aspect of monster vengeance is still retained in the secular masochism of environmentalism. Godzilla is our own fault, just as “the creature” was Dr. Frankenstein’s fault. Just as global warming is our fault. Of course, pollution is indeed a serious threat, as are the many other environmental problems we face. The many television, film, and literary plots revolving around the environment confirm that it ranks as one of our worst fears. Interestingly, doing something to ease the threats often requires an admission of our own complicity in bringing them about.

2

If, as Freud suggested, technology is our prosthetic attempt to become God, will we inadvertently become a monster god? And if we’re not actually becoming God, are we still playing God too much, with all this new power to manipulate nature, splitting atoms, genetically engineering food, robotically enhancing our bodies, chemically enhancing our minds, and designing our babies?