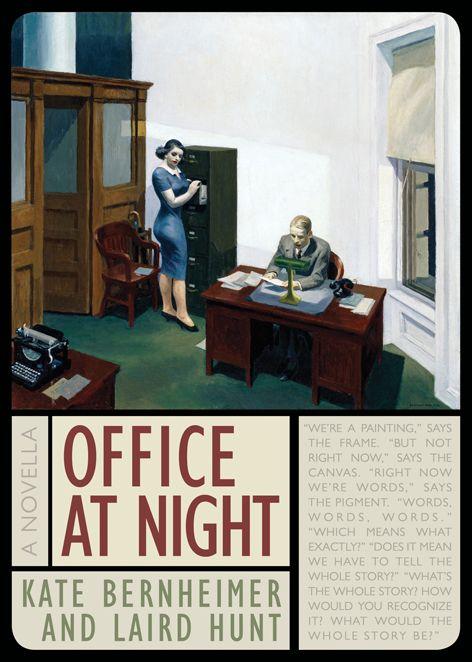

Office at Night

Authors: Kate Bernheimer,Laird Hunt

Copyright © 2014 by Kate Bernheimer and Laird Hunt

Cover image: Edward Hopper,

Office at Night,

1940. Oil on canvas, 22 3/16 x 25 1/8 inches unframed. Collection: Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. Gift of the T. B. Walker Foundation, Gilbert M. Walker Fund, 1948. Used by permission of the Walker Art Center.

Cover and book design by Linda Koutsky

Support for the project was provided in part by the McKnight Foundation.

ISBN: 978-1-5668-9391-6

Coffee House Press books are available to the trade through our primary distributor, Consortium Book Sales & Distribution,

cbsd.com

or (800) 283-3572. For personal orders, catalogs, or other information, write to:

[email protected]

.

Coffee House Press is a nonprofit literary publishing house. Support from private foundations, corporate giving programs, government programs, and generous individuals helps make the publication of our books possible. We gratefully acknowledge their support in detail in the back of this book.

Visit us at

coffeehousepress.org

.

Office at Night: A Novella

was co-commissioned by the Walker Art Center and Coffee House Press in association with the Walker’s presentation of

Hopper Drawing: A Painter’s Process,

April 16–June 20, 2014. The authors were “In residence” in the painting, and tasked to co-write a novella based on it. This book is the result.

For Marge Quinn

CONTENTS

AFTERWORD

: An Interview with the Authors

H

e has suddenly realized the window is open. He can feel it. But how far open? And who opened it? Chelikowsky. His grandfather owned a brewery. Came to the new country with a handful of hops in his pocket. Died of a pulmonary embolism at the age of forty-nine. Left his son, Chelikowsky’s father, on the Lower East Side with a cart and donkey and two hundred pounds of plums he couldn’t unload. Debts. So he went north and west, all the way to Hell’s Kitchen, did the father, who died even younger, with even less, and now Chelikowsky, failed painter, failing businessman, with his own office, is hoping to make it to fifty, and maybe celebrate a little, only someone has opened the window and he doesn’t know who. The new girl? Couldn’t be. The window weighs a thousand pounds in the summer, when the wood swells. He’s strong, Chelikowsky, a wiry ox, and he can barely budge

it. Sneak a glance over at her? He can feel her looking at him, always looking. Maybe she’s got secret muscles. Some of them do. Once he went out walking up Ninth Avenue with a girl who accepted the one kiss he gave her, then knocked him out cold when he attempted a second. He sneaks a glance. So quick you can’t see it. So quick he sees nothing. Just a girl-shaped blur.

He loves his office. Has an apartment on Thirty-Eighth he can barely stand to set foot in. Somehow inherited a cat from a friend’s cousin that uses a two-foot dead space behind a wall in the kitchen as its toilet. The cat doesn’t have a name. He would never bring it here. Jesus H. Christ no way would he let that cat into this office. Even if it is cute. A cutesy cat. He doesn’t even like cats. He thinks maybe they make him sneeze. Once he threw his cat across the room. Just picked it up and threw it. Then felt bad, sure, but not that bad, because before it got to the other side of the room, he had run over and caught it.

He is speedy, is Chelikowsky. In high school he could run well under eleven seconds in the hundred-yard dash. Is someone trying to kill him? That’s the question that is preying

on his mind. Not ten minutes ago he picked me up and used me to call his mother and came very close to telling her. Telling her that he thought someone might be trying to kill him. What would happen if he stood, turned, shut the window? he thinks. Is it even open? He tries one of his quick glances. Again so fast you can’t see it happen. He is expecting a client. Over the phone, over

me,

the case sounded interesting. But complicated. Like a Chinese puzzle. He hates those. There is a guy down on the corner who sells them. Five cents a pop. Make your fingers hurt and your head explode. Why are they always complicated, his cases? he wonders. Chelikowsky used that word,

complicate,

when he hired her, this new girl. He simply can’t bring her name to mind.

I’m a mind-reading telephone. Nifty, right? Lots of us can read minds. I mean lots of what’s in this room. See things. Know things. Why wouldn’t we? Look around you. There, wherever

you

are. Imagine what’s reading your mind. What’s not?

He used to have a wife, did Chelikowsky. Gladys. He has known three other guys with ex-wives named Gladys. His Gladys had loved gladiolas. It was a joke between them. In

the early, giddy, gaudy days. In the summer, he put on short pants and a boater and took her to the boardwalk at Coney Island. Now Gladys is gone, even long gone.

Anyway, sometimes Chelikowsky sleeps here. Turns off the desk light, leans back in his chair, lets the night glide by. Chelikowsky did two years at Hunter, studied English, was still painting. His mother’s pride for two years. Then,

boom,

done. His mother has seen this office. She says she doesn’t like the chair right next to the door. Says it’s too close to the filing cabinet. Says it is too red. Says the desks are too red and too close together. “It’s not decent to be sitting alone in an office with a girl,” she says. She says she doesn’t like typewriters either. They frighten her. But me she likes. She has used me often enough. Still, sometimes she will meet him at the lunch counter across the street. This is where she says all these things about his office to him. He takes it, the good with the bad. She is his mother, after all. He had whooping cough that turned into pneumonia when he was a boy. She didn’t sleep for two weeks. Caring for him. His mother. They both drink their coffee black.

“My cases are often complicated—you o.k. with complicated?”

Chelikoswky asked the girl when he hired her. He can feel her eyes on him. She’s in the filing cabinet too much. It’s like a mania. Some kind of condition. Granted, he asked her to make a dent in his paperwork. The last girl left it a mess. She used it to store her toothbrush. He found it, along with an empty tin of Colgate tooth powder, filed under M. Why under M? Her name was Janice. Janice Jones. He called her JJ. Sometimes he would follow her. He would leave a little after she did and trail along behind her. He wasn’t very good at it. She just did things like buy a pork chop and some milk then get on the subway. He was pretty sure she knew he was following her, though she never let on. Then one night he turned around and saw that she was following him. She was holding her little bag from the butcher’s and wearing a grin. Good old JJ.

They tried it on once and it didn’t work out so well, because he was already tight when they started. JJ quit working for him to get married to some other guy. And because he, Chelikowsky, was “kind of a crumb.” According to her. Though it was true that after they tried it on and it didn’t work so well, he shoved her out the door. Just a little shove. Placed

his palm into the handsome concavity between her shoulder blades and good-bye. He never shoved Gladys. Even if he

had

thrown and caught a cat. He would never shove Marge. Marge is her name. Chelikowsky smiles. Even though you could never tell. Marge, Marge, Marge, Marge, Marge.

Is it Marge who wants to kill me? Chelikowsky wonders. She has just handed him a document, plucked from the cabinet and dated two years ago. She didn’t say a word—just strode over and plopped it onto the desk in front of him. He has read it twice and can’t make heads or tails. “Dear Abraham Chelikowsky” it starts. “May we meet next week at Madison Square? I will trust that you recall my situation so recently and gravidly discussed between us. I will wear the same hat as I did in the old days. Yours most sincerely and diffidently . . .” It is unsigned, bien sur. Who the fuck? It rings no bells. What does “gravidly” mean? A case? He was about to ask Marge why she handed him this two-year-old cryptogram when he noticed the window was open. Wide. Like a mouth. I don’t want to die, thinks Abraham Chelikowsky.

And now I must stop because in just a moment I will start to ring.

I

should shut that window, Marge Quinn thinks. And perhaps I will in a minute, although it always sticks and I’ll have to ask Miss Chan for help. I have asked her for help, Marge Quinn thinks, six and a half times already today, and I don’t like the idea of asking her again. It’s just that the trucks stop at the corner below and the exhaust smell is awful and Abraham gets so awfully grumpy when the window is open. Even, Marge Quinn thinks, when he has opened it himself. Or mostly opened it himself. Miss Chan always helps him. She has such a skill with windows, thinks Marge Quinn.

Marge Quinn of the wide, soft fingers. Marge, whose father arrived in this fine city confined in the hold of the boat. Because of a transgression during the passage. He has the same fingers. He was always gentle, was her father, except when he was killing someone. But that was long ago, Marge Quinn thinks. In the old country. Here he spends his days in a chair by the window of their fourth-floor tenement walk-up. Here he sleeps quietly and doesn’t yell. All the

money she doesn’t need goes to him. He has always been so gentle. Except that once she walked in on him killing someone. Long ago. Where she was born. But she was born here, she thinks. So how could that have been?