No Surrender (22 page)

Authors: Hiroo Onoda

In the course of gunfights with enemy troops or islanders, we captured a carbine and a hunting rifle, but without ammunition they were useless to us, so we buried them deep in the jungle.

A slug from an infantry rifle travels about 670 yards in the first second after firing, but a carbine slug goes only about 500 yards in the first second. The islanders usually had carbines, and if we saw them fire on us from a considerable distance, we knew we had about one second in which to dodge. At night, you can even see a bullet approaching, because it shines with a bluish white light. I once dodged a flying bullet by turning my body sideways.

When Shimada was shot, Kozuka and I had to flee so rapidly that we left our bayonets behind. Later we found bayonets for Thompson machine guns in the house of an islander and filed down the bayonet holders on our guns so that these would fit. The file, incidentally, had been requisitioned.

Our ammunition pouches were fashioned from a pair of rubber sneakers. We first put the cartridges in cloth sacks tied at the top with strings. Each of us carried two sacks inside his pouch, one containing twenty cartridges, the other thirty. The top of the pouch came down over the sides and was fastened with a hook, like a camera case, to keep the contents dry. In addition to the ammunition in the pouch, I carried five cartridges with me in my pants pocket, and there were always five in the gun. Altogether, then, I was always armed with sixty cartridges, enough to enable me to make a getaway even if I stumbled across a fairly large search party.

I had six hundred rounds of machine gun ammunition, and in my spare time I fixed all the good ones so that they could be fired from my model 99. A lot of the bullets were faulty and had to be used for other purposes.

Since I could not use the repeater action on my gun with these modified cartridges, I fired them only when I was shooting a cow or firing a single shot to scare off islanders. There were about four hundred good cartridges in all, which I started using around the time Akatsu defected. They were about gone when I came out of the mountains twenty-five years later. I must have fired an average of only sixteen of them a year.

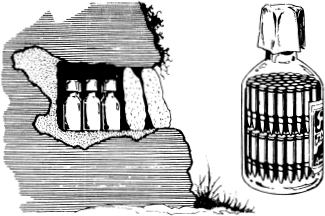

We were very careful about our spare ammunition. We kept it hidden in holes in the sides of cliffs, which we covered with rocks. We inspected the hiding places each year and at the same time put the ammunition in new containers. We marked the ammunition that was definitely good with a circle and that which was probably good with a triangle. We removed the powder from bullets that were too rusty to use and used it in building fires. It could be ignited with a lens we had requisitioned.

The storage of ammunition so that it would be in good condition when needed was very important. After the rifle and machine gun cartridges were stacked in bottles, they were covered with coconut oil. The bottles were hidden in caves, which were then covered with stones.

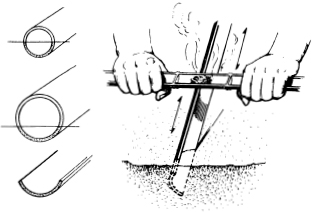

To make a fire at night or when it was dangerous to make smoke, I used split bamboo. One stick was planted firmly in the ground, and the other, holding coconut fiber and gunpowder, was rubbed vigorously up and down against it.

The containers for the ammunition were whiskey bottles and the like left here and there by the islanders. We used rubber from an old gas mask to stop up the bottles. For fear that rats might get in and eat the rubber, we also covered the mouths of the bottles with metal caps that we made from tin cans.

We tried to arrange the rocks covering the mouths of the storage holes to look as natural as possible, sometimes succeeding so well that we had trouble spotting them ourselves. In the course of a year, vines usually grew over them, and sometimes trees fell against them, almost concealing them. If we did not inspect at least once a year, there was a real danger that we might not be able to find them.

As can be seen from what I have said already, the worst years were the early ones, when we were not only afraid to make forays in the open but were at a disadvantage because of Akatsu's weakness. After Akatsu left, the remaining three of us adopted a more aggressive policy that called, among other things, for requisitioning more supplies from the islanders. They, for their part, were enjoying a rising standard of living, which meant that they not only had more goods worth stealing but also left more things about in the forest or in other reasonably accessible locations. Thus, our standard of living tended to rise in proportion to that of the islanders. Shimada's death deprived us of a faithful friend and a valuable worker, but it reduced the supply problem to some extent, if only because the meat from one cow will feed two longer than it will three. Life in the jungle was never easy, but so far as food, clothing and utensils were concerned, it was far easier in the later years than in the first five or ten.

In order to clear the way for the Japanese landing party that we continued to expect, we adopted guerrilla tactics aimed at enlarging the territory under our control and keeping out all enemy trespassers.

We conducted what we called “beacon-fire raids.” We would go to various places in the early part of the dry season and burn piles of rice that the islanders had harvested from their fields in the foothills.

The season for harvesting this rice came in early October, around the time when we dismantled our rainy season dwelling and moved farther up into the mountains. From about halfway up we could see them cutting and bundling the rice. To protect it from the moisture, they spread thick straw matting on the ground and piled the unhulled rice on that. We would wait until twilight and then, approaching stealthily to a nearby point, fire a shot or two to scare the islanders away. This nearly always worked, and after they had fled, we set fire to the rice by sticking oil-soaked rags in the piles and lighting them with matches. We thought of the fires as beacons signaling to friendly troops who might be in the vicinity of Lubang that the “Onoda Squadron” was alive and carrying out its duties.

Matches, which were essential to this type of operation, were not always easy to obtain. They had to be requisitioned, of course, and it was important not to waste them. Whenever we acquired some, we first dried them thoroughly, then shut

them up tightly in a bottle. In principle, we used them only for our beacon raids, relying at ordinary times on other methods, such as rubbing two sticks of bamboo together or igniting a little gunpowder from unusable ammunition with our lens.

The islanders would of course report our raid to the national police force stationed on the island, and the police would come running. We had only a short time in which to set our fire, seize whatever supplies the islanders had left behind, and beat it back into the jungle.

We thought that the local police would report our raids to the American forces, and that Japanese intelligence units would pick up the messages. The raids would, we reasoned, make it difficult for the Americans to neglect Lubang, while at the same time assuring our own people that we had the situation on the island under control. This would presumably make it possible for them to fight on, wherever they were fighting, without worrying about us. The raids would also help convey to the islanders the idea that it was dangerous for them to leave their villages and go into the foothills to work.

From the mountains, Kozuka sometimes called out toward a village, “Don't think you're safe because there are only two of us! One step too far, and you'll be in trouble!” No one could hear him, I suppose, but this was apparently good for his spirits.

Actually, burning the rice in the same places every year increased the danger that the islanders might anticipate our movements and set a trap for us. We therefore varied our tactics to some extent, putting off the raids for a month in some years or for five months in places where two crops were grown each year. We tried to keep them guessing as to where we might pop up. If we could nurture the fear that we might show up almost anywhere at almost any time, that in itself would accomplish half of our objective.

The eighteen years that Kozuka and I spent together were the ones in which I was most actively engaged in guerrilla tactics. This was due to a large extent to the rapport that existed between us. We nearly always saw things the same way, and frequently we needed only to look at each other to decide what we would do next.

Although I had not known Kozuka before I came to this island, the fortunes of war were such that we became closer than real brothers. I respected his spirit and his daring. He, for his part, deferred to me in matters of judgment. Many times we told each other that when our assignment had been carried out, we would return to Japan together. If by chance we never made contact with friendly forces, we would rot together on Lubang. We laughed as we talked over these two prospects.

Then at times when we had found some particularly fine bananas, or handily eluded a search party, or led the enemy a merry chase, we would suddenly say simultaneously, “If only Shimada were here!”

Besides carrying out our beacon raids, we decided to try to collect information directly from the islanders. To go anywhere where there were lots of people would be dangerous, but there were plenty of lonely spots on the island where we might take one of the farmers prisoner as he went to or from his fields.

We singled out a lonely farm hut near the salt flat in Looc. This was near the edge of the jungle, and it would be easy to escape if we ran into unforeseen trouble.

Coming out of the woods at the salt flat, we approached the hut, staying low and keeping a sharp eye on the surroundings, We looked in. Nobody was there, nor was there anything to requisition. Suddenly Kozuka, who had very good ears, whispered, “Somebody's coming!”

He pointed toward the ocean, and when I looked, I saw a man of about forty making his way through the tall grass toward us. We waited silently by the hut, rifles ready. When he was

about three yards away, I leaped out in front of him with my rifle aimed straight at his chest. He let out a surprised yell, then raised his hands.

Kozuka told him in English to sit down, and he began talking quickly in Tagalog, which we could not understand. I motioned to him to shut up, and he did. We led him at gunpoint into the house. Somewhat to our relief, he made no effort to resist.

When I asked him why he had come here, he answered in a combination of English and Tagalog, with many gestures, “I left a dog near here to keep my cows from being stolen. I came to take the dog back. I'm not a Yankee spy. Don't kill me.”

Not wanting to stay in the house too long, we took him into the mountains, where we questioned him thoroughly about conditions on the island. He told us everything he knew, down to the price of cigarettes and the average pay for a day's labor. Throughout the questioning, he continued to shake with fright. When we decided we had learned all we could, we told him to go home and go to bed. His face registered great relief.