No Surrender (21 page)

Authors: Hiroo Onoda

When it was not raining, I slept on mountain slopes where the inclination was ten to fifteen degrees. It was necessary to put my backpack or a log under my feet to keep from sliding down. I chose a place with bushes or trees for cover and slept fully clothed.

The reason why we slept on sloping ground was simply that this way, if we were suddenly awakened, we could see what was around us without raising up. Actually, during my entire thirty years on Lubang, I never once slept soundly through the night. When we slept on the ground outdoors, I shifted my body often to keep my limbs from getting numb.

I kept a sort of calendar, which after thirty years was only six days off the real calendar. My calendar was based largely on memory and the amount of food left, but I checked it by looking at the moon. For instance, if I picked ten coconuts on the first of the month and we used one a day, the day we used the last one would be the tenth. After making this calculation, I would look at the moon and see whether it was the right size for that day of the month.

When search parties were looking for us and we were moving around every day, I tended to lose track of the date. When that happened, I would start by looking at the moon and then try, in consultation with Kozuka, to figure out how many days had passed since some known date.

The moon was our friend in another respect as well, because we usually moved from one encampment to another at night. Kozuka often said, “The moon isn't on anyone's side, is it? I wish the islanders were the same way!”

Our haircut routine was another help in keeping track of the date. Kozuka once mentioned that back home the people had always celebrated the twenty-eighth day of each month as sacred to a local Buddhist deity. He said they had always eaten a special noodle dish on that day. This reminded me that when I was a boy, the barbers had always put out signs toward the end of the year asking people to have their children's hair cut by December 28 to avoid the year-end scramble. I suggested to Kozuka that we commemorate his hometown's

monthly celebration by cutting our hair on the twenty-eighth of every month, and that is what we did. Somehow this seemed all the more appropriate to me because on the days when we did cut each other's hair, we were for a short while children again. Afterward, we often figured the date by counting the number of days since our last haircut. This was easy to remember.

We were particularly careful with the last haircut of the year, because it was a psychological boost to open the year with our heads looking spic and span.

On New Year's Day we made our own version of “red rice,” that is, rice cooked with red lentil beans. This is served in Japan on festive occasions. We had no lentil beans, but there was a kind of string bean that grew on Lubang that we used as a substitute. On New Year's Day, we also made a special soup out of meat and papaya leaves, flavored with citron. This was intended as a substitute for the meat and vegetable soup called in Japanese

ozÅni

, which is always served in the New Year season.

On the morning of the first day of the year, we bowed in the direction of the emperor's palace, which we considered to be north by northeast. We then formally wished each other a good year, renewed our pledge to do our best as soldiers, and repaired to our feast of “red rice” and

ozÅni

.

We also celebrated our birthdays, and I remember one or two birthdays that I commemorated by giving myself a newly made cap.

Every morning I brushed my teeth with fiber from the palm trees. After I washed my face, I usually massaged the skin with kelp. When I wiped off my body, I often washed my underwear and my jacket at the same time. Since we had no soap, this amounted to rinsing the clothing in plain water, but sometimes I removed the grime from the neck and back of my jacket with the lye from ashes. I put the ashes in a pot and poured

water over them. When the water cleared, I transferred it to a different pot and soaked the clothes in it. We had to be careful to hang our clothing in an inconspicuous place to dry.

There were several clear rivers, but during the whole thirty years I took a real bath only on those occasions when we cut up a cow and got blood and ooze all over ourselves. There is no such thing in the mountains as a valley with just a stream and nothing else. The valleys are also the roads. Except in the narrowest ravines deep in the mountains, we were afraid to undress to the skin, even at night. In the daytime, we bathed the upper parts of our bodies by pouring water over each other. In the evening we each washed off the lower parts of our bodies just before sunset. I would never have done anything so dangerous as to strip completely.

We took as good care of our guns and ammunition as we did of ourselves. We polished the guns with palm oil to keep them from rusting and cleaned them thoroughly everytime we had a chance.

In cool weather, the palm oil congealed. Then we just wiped off the guns and waited until later to oil them. When they got wet, they had to be completely disassembled and cleaned piece by piece. If there was no time for this, we oiled them liberally and waited for fair weather. Since exposure to water tended to make the butts rot, we occasionally had to remove the ammunition and hang the guns where the smoke from our fire would dry them out. The gun butts and slings gradually absorbed so much palm oil that the rats would gnaw at them, particularly the slings, and when we stopped at a place where there were lots of rats, we were forced to hang the guns out of reach on vines.

More troublesome than the rats were the ants. It would be no exaggeration to say that the mountainous section of Lubang was one enormous anthill. There were many varieties of ants. Some of them liked damp places; others thrived only where the ground was virtually parched. Certain types gathered together leaves to make their nests. To us, the biggest nuisance was a type of ant that carried about bits of dirt. These, the most numerous of all, were always crawling into our guns and leaving their dirt. If I just set my gun down for a while on top of my pack, almost immediately a stream of ants would start for the gun butt, and in the process some of them would enter the barrel and deposit dirt in the moving parts. Even a little dirt could cause the guns to jam. When the ants appeared, we would hang the guns from the branch of a tree. There was usually enough wind to keep them from being able to climb very high.

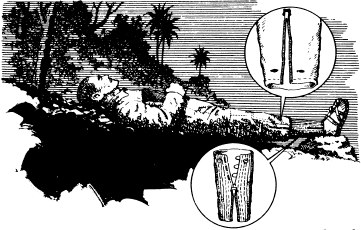

Two kinds of rattraps: the one at left was made of wood; the door would close when the bait was taken. The cloth bag at right was placed near my head when I slept. It would rustle when the bait was taken, then I would close it. The bait was coconut lees.

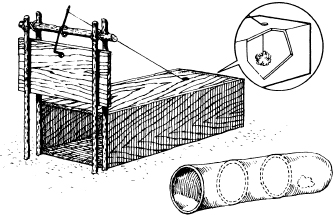

The snare at left was for jungle fowl, which tasted like pheasant. When the bird put its legs into the circle, the other end of the rope was pulled.

Right

, a soft copper loop tied to a tree at the height of the animal's neck was effective for snaring wildcats.

The ants also caused us bodily harm. There are at least five varieties that have stingers like those of bees. These attack the softer parts of the body, and if you are not immune, the sting swells up immediately. Once when I was stung inside the ear, my eardrum became so swollen that I could not hear with that ear for a week. The wound bled a number of times, and I had a fever.

Speaking of stings, there are also lots of bees on the island. Great swarms of them fly around the bushy area near the foot of the mountains like huge sheets. I have seen swarms thirty yards wide and a hundred yards long, flying along with “lookouts” fore, aft and on either side. If we came across one of these swarms, the only thing to do was make for the woods, or if there was not enough time, cover our heads with a tent or clothing and lie flat on the ground. If we made the slightest motion, they would attack. We had to breathe as lightly as possible until the swarm had passed over.

I was also bitten several times by centipedes. If one of these bites a person on the hand, his whole body swells up for a time; even after the swelling is gone, the bite takes a long time to

heal. I was bitten on the right wrist in January, 1974, and the bite has not healed as I write these pages months later.

Under fallen leaves there were apt to be scorpions. When we slept outdoors, we always cleared off a place about three yards square, but even so I woke up in the morning several times to find a scorpion hiding under the rock I had used for my pillow.

Other unattractive residents of the jungle include snakes as big around as a man's thigh.

Every gun has its own quirks. At first the model 99 that I used for thirty years fired about a foot to the right and below the mark at a distance of three hundred yards. After a time I managed to fix the sights so that the aim was more accurate, but I was never able to reduce the error to less than three or four inches.

The stock of this gun was about an inch and a quarter shorter than normal, because at one point I had to remove the butt plate and cut off some wood that had rotted. After replacing the plate and putting in new screws, I was pleased to find that the gun was better suited to my size than before.