New York at War (31 page)

Authors: Steven H. Jaffe

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #United States

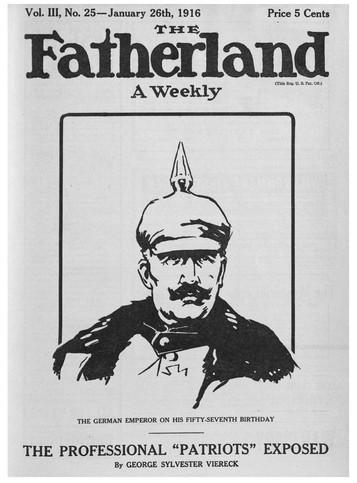

Celebrating the kaiser’s birthday: the cover of

The Fatherland,

January 26, 1916. JOSEPH MCGARRITY COLLECTION. DIGITAL LIBRARY, VILLANOVA UNIVERSITY,

DIGITAL.LIBRARY.VILLANOVA.EDU

.

Among the hundred thousand readers claimed by

The Fatherland

were, unsurprisingly, many New Yorkers of German birth or ancestry. A remarkably diverse group, German Americans abruptly found themselves having to sort out where they stood in relation to their homeland’s war effort. After the

Lusitania

sinking, the number of German aliens applying for American citizenship in New York quadrupled. But others struggled with mixed feelings. A young writer named Hermann Hagedorn, raised in Brooklyn and educated at Göttingen and Harvard, spoke for many of his fellow German Americans in 1914: “Soberly gratified though I might be at every German setback, every German victory set my Teutonic heart beating faster.” He would eventually become an ardent supporter of the Allied cause, convinced that only the defeat of Germany could lead to a new world of “Free Peoples Triumphant.” Arguing with his pro-German brother Addie, he warned that “this country would be split into fragments as our family is now split, the members torn from each other and each member torn within himself,” unless all Americans embraced the Allies. But such convictions came, as Hagedorn admitted, at the price of a painful inner struggle with his German identity.

13

Most vocal among New York’s German population were those who expressed pride in Germany’s war aims. On August 4, 1914, thousands of young men, reservists in the German army, marched up Broadway singing “Die Wacht am Rhein,” making sure to sing louder as they passed the British consulate. When some brawled with English and French reservists who tried to seize their banner, Mayor John P. Mitchel banned all foreign flags from public display. Facing the Royal Navy’s blockade of the German ports, most of these German sympathizers ultimately stayed in New York. But the fervor and pride they felt ran deep in Yorkville, Williamsburg, Astoria, and the city’s other German enclaves. When the

Brooklyner Freie Presse

solicited funds from its readers “to help the widows and orphans of their suffering countrymen in Germany and Austria,” the paper distributed thousands of souvenir Iron Crosses so subscribers could remember “the heroic deeds of the German soldiers for which it is bestowed.” Manhattan’s German-language dailies, like the

Staats-Zeitung

and the

New Yorker Herold

, called for an embargo on American aid to the Allies. While the papers deplored the loss of life on the

Lusitania

, they also argued that the munitions the English liner was carrying made it a legitimate target.

14

German immigrants and their children who had long recited the credo “Germania our mother; Columbia our bride” saw no reason to quell their voices simply because so many of their fellow Americans favored the Allies. Were they not also Americans and entitled to speak freely? Why should they not buy German war bonds and applaud their fatherland’s military ambitions just as other New Yorkers backed England and France? “Organize, Organize!” Viereck exhorted his readers. Though many “ridiculed the hyphen” that distinguished German Americans from their fellow citizens, he insisted, “we shall make it a virtue.”

15

Other New Yorkers also leaned away from the Allies. The city’s Irish population, still large, included numerous friends of the insurgency that would culminate in the Easter 1916 uprising in Dublin against British rule. John Devoy, editor of the

Gaelic American

, and his comrades in the city’s Clan na Gael made New York the most important place outside Ireland for raising funds and smuggling supplies to Sinn Fein and the Irish Republican Brotherhood as they prepared their rebellion. To be sure, New York’s Irish community also included nationalists who believed Irish home rule would follow an Allied victory. “I say not down with England but up with Ireland,” lawyer William Bourke Cockran told a Carnegie Hall audience. But Devoy and many others found little to admire in the British war effort and believed that a victorious Germany would press a defeated England to grant Irish independence. Indeed, by 1915, Jeremiah O’Leary, a militant well-known on both sides of the Atlantic, was publishing his scathingly anti-British satire magazine,

Bull

, out of a Park Row office, using secret funds from von Bernstorff’s bank account.

16

Eastern European Jews also scrutinized the Allied cause skeptically. By the war years, Jewish emigrants from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires had made New York the largest Jewish city in the world. On one hand, New York Zionists hoped that British victories against the Ottomans would lead to the recognition of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. On the other hand, the socialism that many Jews brought with them from Europe dictated that the war be rejected as a capitalist bloodbath. Above all, most Jews simply could not stomach the fact that the bitterly anti-Semitic czarist regime was one of the principal Allies. Many of the 1.5 million Jews on the Lower East Side and in Harlem, Brooklyn, and the Bronx had fled Russia and Russian Poland to escape pogroms, an oppressive draft, and the reactionary policies of Czar Nicholas II’s government.

In 1915, bloody attacks by czarist troops on Jewish villages—scapegoats for the Russian army’s blunders on the Eastern Front—only further outraged New York’s Jews, while also making liberal Gentile advocates of the Allied cause squirm. Harry Golden, a young boy selling Yiddish papers on a Lower East Side corner, knew how to lure customers with breaking war news sent from Eastern Europe: “No matter what the outcome of the skirmish I shouted ‘Russians retreat again!’ I shouted it even if the Russians advanced.” Moreover, the kaiser’s main ally, the Austro-Hungarian emperor Franz Josef, was a known foe of anti-Semitism. “Franz Josef was the old reliable,” Harry Golden recalled. “The East Side Jews adored him.” Russian bigotry and Austrian tolerance made it hard to view the Allied cause as a clear-cut crusade of “democracy” against “autocracy.” Shrewdly, Viereck’s

Fatherland

celebrated Franz Josef with a lavish cover portrait, while on another cover a cartoon depicted the cruel, sword-wielding czar intimidating a Jewish captive.

17

“There is no room in this country for hyphenated Americanism,” former president Theodore Roosevelt announced to an auditorium full of New York’s Knights of Columbus in October 1915. Roosevelt repeated his message in numerous speeches and interviews, specifying his main target: “those professional German-Americans who seek to make the American President in effect a viceroy of the German Emperor.” Roosevelt had become the most visible spokesman for Preparedness, a nationwide movement sponsored primarily by wealthy businessmen and professional men in New York, Chicago, and other large cities. Preparedness men urged the need for rearmament and a national draft. Most in the movement’s organizations—the National Security League, the American Defense Society, and the American Protective League—were openly pro-Allied and anti-German. They were also profoundly anxious about ethnic pluralism and the complex loyalties it implied.

18

Preparedness advocates sought to alarm and awaken their countrymen by pointing to the dire vulnerability of their nation’s largest metropolis. In a 1915 book entitled

America Fallen!

J. Bernard Walker, a former

Scientific American

editor, argued that the new long-range guns the government had been placing since the 1890s in the six forts now guarding New York harbor might, in fact, fail to deter a German invasion, even though the guns made New York the most heavily defended place in the country. Evading their shells, enemy submarines could take Fort Hancock on Sandy Hook, Fort Hamilton at the Narrows, and the Brooklyn Navy Yard under the cover of night. The German surface fleet could then bombard Manhattan’s signature skyscrapers—the Woolworth Building, the Singer Building, the Municipal Building—to terrify New Yorkers into submission and extort a $5 billion ransom from them.

The Battle Cry of Peace

, a popular 1915 silent film produced by a Briton, J. Stuart Blackton, and endorsed by Preparedness groups, portrays “an unnamed foreign power” using ships and planes to bomb and shell lower Manhattan—a feat made easy after secret agents gain control of the city’s pacifist movement and lull naïve New Yorkers into a state of utter defenselessness. Walker and Blackton unwittingly echoed the very invasion plans the German high command had shelved a few years earlier. (They also echoed forgotten concerns from the 1880s and 1890s, when mass-circulation papers like

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly

and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York

World

warned of the port’s vulnerability to another potential threat, an artillery bombardment by Spanish warships, although an attack on New York does not seem to have been on the Spanish agenda, even during the Spanish-American War of 1898.)

19

But proponents of Preparedness were also doing something new: they were calling on all Americans to worry about the fate of a city many of them distrusted or even despised. Manhattan, with its bankers and immigrant masses, had come to seem a malevolent foreign force to many; by the 1890s, some Americans openly viewed Wall Street and Ellis Island as national threats. But some of the Preparedness visionaries of 1915 saw these attitudes as mistaken and dangerous. While millions viewed New York as an alien excrescence, the reality, they implied, was that New York was the essence of America: a rich, powerful, yet utterly vulnerable place, oblivious to how its own self-indulgence and softness lay it open to enemy assault. A successful attack on New York would be an attack on America, an attack the slumbering nation might not survive if it did not arm itself in advance.

On the other hand, some Preparedness lobbyists did harbor agendas that implicated New York and other large cities as threats to national security in and of themselves. While there was room in the movement for liberals who viewed Prussian militarism as a menace to world progress, many Preparedness activists were wealthy Anglo-Saxons of deeply conservative views. To these men, military preparation would not only defend America against the external foe, Germany, but also foster a national unity that would help combat internal enemies—labor unions, activists who favored an eight-hour workday, leftist radicals, and recent immigrants who allegedly harbored divided loyalties.

A long-range gun at Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island, guarding New York from naval attack, c. 1908. GEORGE GRANTHAM BAIN COLLECTION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS.

Fear of internal enemies was already well embedded in the consciousness of New York conservatives. After the Civil War, National Guard regiments in New York and other American cities—often composed mainly of wealthy volunteers for whom membership represented a mark of status as well as patriotism—began constructing armories. These imposing castle-like fortresses housed weapons, provided space for regimental drills, and served as citadels steeling the city, in the words of the editor George W. Curtis, “not only against the foreign peril of war, but the domestic peril of civil disorder.” New York’s sprawling slum and sweatshop districts harbored threats to the safety of the city’s propertied classes, Curtis and the Guardsmen believed. The Draft Riot, the Paris Commune of 1871 in which radicals seized control of the French capital, the rise of a vigorous American labor movement challenging the prerogatives of capitalists, the violent strikes that paralyzed American railroads in 1877, and the calls of a small but vocal array of immigrant anarchists for class war all figured in the thinking of armory builders. (So, perhaps, did apocalyptic novels like Joaquin Miller’s

Destruction of Gotham

[1886] and Ignatius Donnelly’s

Caesar’s Column

[1890], which pictured New York conquered and ravaged by an enraged, brutalized working class.) Behind brick and granite walls, they stockpiled guns and ammunition to protect the established social order and prevent revolution.

20