New York at War (26 page)

Authors: Steven H. Jaffe

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #United States

Hardship at the bottom seemed unmatched by any pervasive suffering at the top. War contractors stood to make “killings” if they played their cards right. Some sought quick and easy profits by selling inferior or spoiled merchandise—“shoddy,” as it was called—to a government too distracted to inspect every lot of goods or to purchasing agents who might get a kickback if they looked the other way. Honorable or not, war contracting sustained the city’s lopsided distribution of wealth, as well as the widely held conviction that a small class of profiteers was enjoying luxuries beyond the reach of the urban masses. “Our importers of silk goods and our leading jewelers are selling their finest goods at the highest prices,” the

Herald

noted in October 1862. War-generated ostentation pleased members of the established elite as little as it did the working poor. Complaining of a saddler’s wife seen buying pearls and diamonds at Tiffany’s, Maria Lydig Daly sniffed at magnificent carriages filled with “the commonest kind of humanity. Old women who might be apple-sellers or fruit-carriers are dressed in velvet and satins.”

19

Late May 1862 found Corporal Thomas Southwick far from New York, trying to climb a Virginia hill “thick with glutinous blood, causing me to slip and almost tread upon one whose life had gushed out of an ugly wound behind his ear.” Long gone were the fantasies of seizing rebel flags or rescuing generals. So were the illusions of most New Yorkers, whether at the front or at home. The newspaper casualty lists with their grisly shorthand (“Thomas McGuire, Co. A., leg amp; . . . H. Mcilainy, Co. I, forehead, severe”) arrived now with a numbing regularity—numbing except to the families who learned from them of a brother wounded, a husband killed. With one son dead and another missing an arm, Columbia College law professor Francis Lieber and his wife, Matilda, came to scan the daily papers with “drained and feverish eyes” for news of their third son (who survived the war physically unscathed).

20

Many of the surviving volunteers, like Thomas Southwick, had had enough. “Will this war ever cease? I cannot find a satisfactory answer,” he wrote in his diary. Rather than stay in the army at the end of his two-year enlistment, he returned to work as a car painter at the Third Avenue Railway in May 1863, bearing memories of Gaines’s Mill, Malvern Hill, and Fredericksburg that would last him a lifetime. If bullets and camp fever took the lives of rich boys as well as poor ones, it was in Thomas Southwick’s New York—a city of working-class neighborhoods, workshops, and saloons—that a bitter phrase increasingly fell from the lips of veterans and noncombatants alike: “A rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

21

Several hundred miles to the south, Confederates had their own understanding of New York City’s role in the conflict engulfing them. Dependent for decades on New York’s resources to finance the cotton economy, resentful of the profits New Yorkers made from the cotton trade, secessionists concocted vengeful fantasies. Edmund Ruffin, a Virginian honored by being allowed to fire one of the first cannonballs against Fort Sumter, brooded frequently about Manhattan. Ruffin filled his diary with dark musings on the apocalyptic strife he predicted would befall the city once its Southern sources of wealth disappeared and its underlying decadence surfaced. In 1860 the Charleston

Mercury

had serialized Ruffin’s novel,

Anticipations of the Future

, written as a retrospective “history” of the coming struggle between North and South. Faced with the loss of Southern trade, spiraling food prices, and an unruly mass of unemployed workers, “the city of New York broke into open rebellion. Thousands of rioters raided the gun stores and plundered the liquor shops. The police were helpless. . . . Banks were broken open and their vaults robbed. Churches were looted. . . . Drunk and gorged with plunder, the mob set the city on fire. A high wind whipped the flames into a hurricane of fire, and when morning came New York was a blackened, charred ruin.”

22

Ruffin’s vision represented more than merely a fantasy of Southern triumph. It was the start of a tradition in which its enemies would perceive New York not just as a narrowly defined military objective, but also as an encompassing symbol of moral and cultural evil. The city became a target for attack in sweeping and emotionally urgent terms. In previous wars, belligerents had targeted New York as the administrative center of a colonial hinterland, as the key to the Hudson River, and as one of several major coastal ports. Now, as the North’s capital of commerce, finance, industry, and intellectual opinion, New York represented something larger to Southerners. Boston might be the citadel of abolitionism, and Philadelphia might be filled with meddlesome antislavery Quakers. But New York was the true Sodom, the place that exemplified and reveled in everything that was rotten about the North: the disorder of “free labor,” capitalist greed and arrogance, social chaos and conflict. Of course, it was precisely because so many Southerners were familiar with New York, tied into its web of cotton financing and enticed by the charms of its goods and services, that the wartime renunciation had to be so vehement. The seductions of the place, as well as its power and conceit, needed to be checked. As large as it was, New York in the eyes of its enemies became even larger, the embodiment of everything the Confederacy was fighting against.

One man carried the preoccupation with New York into the inner sanctum of the Confederate cabinet. Stephen Mallory, Jefferson Davis’s navy secretary, envisioned an ironclad steamer that could win the war, its metal armor impervious to shellfire as it sank wooden-hulled Union ships at will. In March 1862, after his prototype, the

Merrimack

, wreaked havoc on Union shipping in Virginia waters, Mallory wrote excitedly to its commander, Franklin Buchanan, of what would follow. The ironclad would be ordered north to New York harbor to “shell and burn the city and the shipping. . . . Peace would inevitably follow. Bankers would withdraw their capital from the city. The Brooklyn Navy Yard and its magazines and all the lower part of the city would be destroyed.” Such an attack, Mallory concluded, “would do more to achieve our immediate independence than would the results of many campaigns.”

23

In the end, the

Merrimack

would not lob shells into New York. By the time Mallory wrote his letter, the ship had already been checked in battle by the ironclad

Monitor

, dispatched from New York harbor. Buchanan himself pointed out to Mallory the obstacles to a successful foray: the unlikelihood of finding Sandy Hook pilots to guide the

Merrimack

through the Lower Bay’s treacherous sandbars and the possibility that New York’s outer forts would open fire on it. Buchanan did concede, however, that if it reached the inner harbor, it could batter the city’s houses and ships.

24

Through the early months of 1862, New Yorkers feared just such an onslaught as the one that Mallory envisioned. More precisely, after the Union navy caused a diplomatic crisis by removing two Confederate envoys from the English-bound vessel

Trent

on the high seas, they feared two possible onslaughts: one from the much-discussed

Merrimack

, the other from the Royal Navy. George Templeton Strong worriedly questioned “whether we can stop iron-plated steamers from coming up the Narrows and throwing shells into Union Square.” Lincoln’s willingness to appease the English to avoid a transatlantic war, and the blowing up of the

Merrimack

in May, allowed New Yorkers to breathe a sigh of relief, but their anxieties resurfaced throughout the war. In September 1862, Union navy secretary Gideon Welles scoffed in his diary that “men in New York, men who are sensible in most things, are the most easily terrified and panic-stricken of any community. They are just now alarmed lest one iron-clad steamer may rush in upon them one fine morning while they’re asleep and destroy their city.”

25

A few weeks later, however, such alarm seemed less ludicrous. On November 2, forty-four survivors from vessels sunk by the eight-gun Confederate navy steamer

Alabama

arrived in Boston harbor. The survivors carried a message for the New York Chamber of Commerce from Raphael Semmes, the

Alabama

’s captain, informing the chamber “that by the time this message reached them, he would be off” the port of New York. After burning nine New England whaling ships in the Azores, Semmes had turned to the Atlantic coast, where over the course of October he captured ten Northern vessels, most of them bound from New York to Europe with grain and flour. Some of the ship captains showed Semmes papers indicating that their cargoes belonged to English owners, but the Confederate commander was not impressed. “The New York merchant is a pretty sharp fellow,” he later wrote, “in the matter of shaving paper, getting up false invoices, and ‘doing’ the custom-house; but the laws of nations . . . rather muddled his brain.” Declaring the documents invalid, Semmes sank eight of the cargo-laden ships.

26

Next, Semmes planned to bring the war to New York’s doorstep. Recent copies of the

Herald

and other New York papers found on board his prizes reassured Semmes that the harbor was lightly defended by the navy, which had dispatched gunboats that he managed to bypass on his way toward the city. Aware of the large number of cargo vessels riding in the Lower Bay, Semmes determined, in the words of one of his officers, “to enter Sandy Hook anchorage and set fire to the shipping in that vast harbor.” But on October 30, with the

Alabama

still two hundred miles east of Sandy Hook, Semmes decided that the move was too risky because his coal supply was running low. The

Alabama

pulled off toward the Caribbean, to the disappointment of the crew. “To astonish the enemy in New York harbor,” Master’s Mate George Fullam noted in his log, “to destroy their vessels in their own waters, had been the darling wish of all on board.”

As Semmes predicted, the city went “agog” as news spread of his audacious message to the Chamber of Commerce. Although Union navy commander Henry Wise argued that “any of the armed ferry boats now at the Navy Yard would make toothpicks of her [the

Alabama

] in five minutes,” New Yorkers were not so sure. “It seems strange that the energy and resources of the country cannot result in ridding the ocean of a pestering pirate,” Horace Greeley’s

Tribune

complained.

27

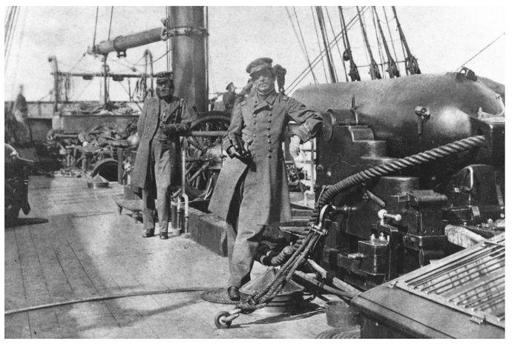

Captain Raphael Semmes (center right) poses next to one of the Confederate raider

Alabama’s

guns, 1863. NAVAL HISTORY & HERITAGE COMMAND PHOTOGRAPHIC COLLECTION.

In August 1864, Confederate “pirates” would return to New York waters. The three-gun cruiser

Tallahassee

, at seventeen knots one of the fastest steamers in the world, slipped out of Wilmington, North Carolina, past a Union blockade, under orders from Stephen Mallory to wreak havoc on Union shipping along the East Coast. Four days later, cruising off Long Island’s south shore and Sandy Hook, the

Tallahassee

’s captain, John Taylor Wood, commenced a two-day looting and burning spree. Soon the waters off New York were littered with the wrecks of twelve brigs, barks, schooners, and ships, scuttled or burnt to the waterline. Wood loaded the scores of crewmen and passengers he captured onto other vessels and sent them into Fire Island and the city with the news of his presence. Captain Reed of the captured brig

Billow

told a reporter that Wood “appeared to be a very affable man, and said he was doing what it was not pleasant for him to do.” Wood told Reed that his mission was to “slacken up the coasting trade so that ‘Uncle Abe’ would be glad to make peace.” But the commander also warned several of the prisoners he released that “he was coming into New-York harbor.”

28

Given Wood’s audacious temperament, his vessel’s unmatchable speed, and the dearth of Union warships in the vicinity of New York (almost all were on Southern blockade duty or Atlantic patrol), he probably intended to make good on his threat. But Wood could not persuade or pressure any of the Sandy Hook pilots he captured to aid him in his plan, which was to maneuver his steamer through the bay’s shoals into the East River, shell anchored ships and the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and then slip through Hell Gate out into Long Island Sound. Instead, Wood decided to turn east and hunt in New England’s shipping lanes. Although he was pursued by Union gunboats, August 26 found the rebel raider safely back in Wilmington, having sunk a total of twenty-eight Northern vessels. New Yorkers, especially ship owners and sailors, breathed a sigh of relief, but they also remembered Wood’s warning that the Confederacy had other cruisers it would unleash against Northern shipping.

29