Nelson's Lady Hamilton (15 page)

Read Nelson's Lady Hamilton Online

Authors: Esther Meynell

Tags: #Hamilton, Emma, Lady, 1761?-1815, #Nelson, Horatio Nelson, Viscount, 1758-1805

134 NELSON'S LADY HAMILTON

doings at St. Vincent echoed not only through the Navy, but through Europe. He was made a Rear-Admiral of the Blue and a Knight of the Bath. His good old father, the Reverend Edmund Nelson, wrote to his son : "Joy sparkles in every eye, and desponding Britain draws back her sable veil, and smiles. It gives me inward satisfaction to know, that the laurels you have wreathed sprung from those principles and religious truths which alone constitute the Hero."

Then came the disastrous attack on Teneriffe, where Nelson lost his right arm, and returned to England in despair, writing to Lord St. Vincent before leaving, " I am become a burthen to my friends and useless to my country. When I leave your command, I become dead to the world; I go hence and am no more seen."

But destiny did not intend that Nelson should be "no more seen." By the December of 1797 he was restored to health, after a period of grievous suffering from his badly amputated arm. He had discovered that his country had need of him, even though he was an admiral with only one arm and one eye. In the fulness of his heart he sent to the vicar of St. George's, Hanover Square, on the 8th of December, a notice to be used on the following Sunday, " An officer desires to return thanks to Almighty God for his perfect recovery from a severe wound, and also for the many mercies bestowed upon him."

And so with recovery of health and hopes, with the promise of a ship—it was to have been the Foudroyant, then just ready for launching— opened the year of the Nile. Inevitable delays occurred before Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson could join his Commander-in-Chief. The fine Sogun Foudroyant was, after all, not ready so soon as expected, so Nelson took instead the 74-gun Vanguard^ and on the last day of April, 1798, joined Earl St. Vincent off Cadiz. On the 8th of May Nelson sailed from Gibraltar with a small squadron, two sail-of-the-line— besides the Vanguard —three frigates and a sloop. His object was to observe the French preparations at Toulon, and discover, if possible, the destination of the large force assembling there. And so the British flag once more entered the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile at Naples things were pretty bad. The Prime Minister, Sir John Acton, was despondent. It was useless, as he assured Sir Gilbert Elliot, for the Italians to arm themselves if they were not aided from the outside, while as for the Neapolitan Navy, their "head-shipman had lost his head, if ever he had any." The meaning is plain, though the English is odd. The British Navy was the only hope, for Austria was a broken reed. Acton urged Sir William Hamilton to inform Lord St. Vincent of their plight and condition. " Their majesties,"

136 NELSON'S LADY HAMILTON

he says, " observe the critical moment for all Europe, and the threatens of an invasion even in England. They are perfectly convinced of the generous and extensive exertions of the British nation at this moment, but a diversion in these points might operate advantage for the common war. Will England see all Italy, and even the Two Sicilies, in the French hands with indifference ? "

But Sir William Hamilton dared not promise much. "We cannot, however," he says, with diplomatic caution, " avoid to expose that His Sicilian Majesty confides too much in His Britannic Majesty's Ministry's help."

It is obvious that Emma had nothing to do with this cold statement—that was not the sort of consolation she was offering the Queen ! And with characteristic energy she did more than merely offer consolation. She wrote to Earl St. Vincent, appealing strongly to his aid and protection for the distressed Maria Carolina. St. Vincent, who called Lady Hamilton the " Patroness of the Navy," and whose courtesy to women was in marked contrast to his severity as a sea-officer, replied as follows:—

"The picture you have drawn of the lovely Queen of Naples and the Royal Family would rouse the indignation of the most unfeeling of the creation at the infernal design of those devils who, for the scourge of the human race, govern

France. I am bound by my oath of chivalry to protect all who are persecuted and distressed, and I would fly to the succour of their Sicilian Majesties, was I not positively forbid to quit my post before Cadiz. I am happy, however, to have a knight of superior prowess in my train, who is charged with this enterprise, at the head of as gallant a band as ever drew sword or trailed pike."

So when the fortunate news arrived that Nelson was once more in the Mediterranean, it seemed that Lady Hamilton was nearer the truth of the British Government's intentions than her husband. The Queen was

But the " expected success " was to be several months delayed. Ill-luck dogged Nelson almost from the time of his entering the Mediterranean, till at last, after many weary weeks, he set eyes on the French fleet among the shoals of Aboukir Bay. On the 2Oth of May a tremendous storm dismasted his flagship. " Figure to yourself," he tells his wife, " a vain man, on Sunday evening at sunset, walking in his cabin with a squadron about him, who looked up to their chief to lead them to glory, and in whom this chief placed the firmest reliance. . . . Figure to

138 NELSON'S LADY HAMILTON

yourself this proud, conceited man, when the sun rose on Monday morning, his ship dismasted, his fleet dispersed, and himself in such distress that the meanest frigate out of France would have been a very unwelcome guest."

And the worst of all was that the very northerly wind which half-wrecked the Vangiiard enabled the whole French armament and fleet under Buonaparte's command to put to sea.

The day before this happened Lord St. Vincent had received orders to detach a squadron of twelve sail-of-the-line, with frigates, from hi< fleet, and to send it into the Mediterranean under the command of "some discreet flag-officer," in quest of the French armament. Lord Spencer had said to him in a private letter, " li you determine to send a detachment, I think it almost unnecessary to suggest to you the propriety of putting it under the command of Sir H. Nelson, whose acquaintance with that part of the world, as well as his activity and disposition, seem to qualify him in a peculiar mannei for that service."

Without such advice St. Vincent would prc bably have chosen Nelson for this important service, as he believed in him strongly, like all wh< had real knowledge of his abilities. Also Nelsoi was already in the Mediterranean. So the Com-mander-in-Chief sent him reinforcements and th< following instructions:—

" I do hereby authorize and require you, on being joined by the Culloden, Goliath, Minotaur, Defence, Betterophon, Majestic, Audacious, Zealous ', Swiftsure, and Theseus, to take them and their captains under your command, in addition to those already with you, and to proceed with them in quest of the armament preparing by the enemy at Toulon and Genoa. ... On falling in with the said armament, or any part thereof, you are to use your utmost endeavours to take, sink, burn, or destroy it. ... On the subject of supplies, I inclose also a copy of their lordships' order to me, and do require you strictly to comply with the spirit of it, by considering and treating as hostile any ports within the Mediterranean (those of Sardinia excepted), where provisions or other articles you may be in want of, and which they are enabled to furnish, shall be refused. . . ."

This was pretty definite; but, to leave no doubt possible, St. Vincent added, "It appears that their Lordships expect favourable neutrality from Tuscany and the Two Sicilies. In any event, you are to exact supplies of whatever you may be in want of from the territories of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, the King of the Two Sicilies, the Ottoman territory, Malta, and ci-devant Venetian dominions now belonging to the Emperor of Germany."

It has been necessary thus to make clear the sort of instructions Nelson had to back him in

140 NELSON'S LADY HAMILTON

order to maintain a sense of proportion when dealing with the much-discussed question of Lady Hamilton's services in helping the British fleet to victual and water at Syracuse.

Nelson knew quite well the condition imposed on the King and Queen of Naples, that not more than four English ships must enter their ports; he also knew that the Queen, at any rate, chafed at this restriction, and was anxious to help the British squadron. He had the instructions of his own Government to take what might be refused him; but he had no desire to use force if it could be avoided. Therefore he wrote to Sir William Hamilton on the i2th of June—

"As I am not quite clear, from General Acton's letters to you of 3 and 9 April, what cooperation is intended by the court of Naples, I wish to know perfectly what is to be expected, that I may regulate my movements accordingly, and beg clear answers to the following questions and requisitions: Are the ports of Naples and Sicily open to his Majesty's fleet ? Have the governors orders for our free admission, and for us to be supplied with whatever we may want ? "

On the 16th of June the van of his squadron hove in sight, and the next day Nelson sent Troubridge and Hardy to Naples, while he himself remained with the rest of his fleet off Capri. Troubridge went at once to the British embassy —Troubridge of whom Nelson had written to Sir

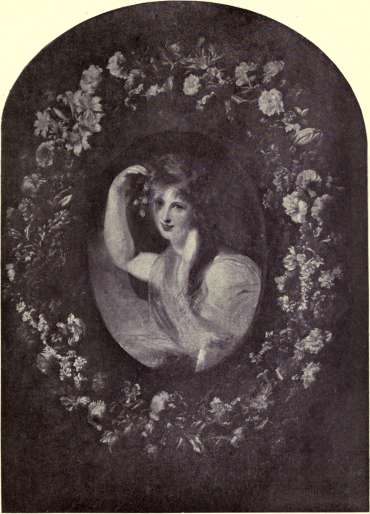

EMMA, LADY HAMILTON

SIR THOMAS LAWRENCE

William Hamilton a day or so earlier, " I send Captain Troubridge to communicate with your excellency, and, as Captain Troubridge is in full possession of my confidence, I beg that whatever he says may be considered as coming from me." To this he added, with that generous love of praise so characteristic, " Captain Troubridge is my honoured acquaintance of twenty-five years, and the very best sea-officer in his Majesty's

service."

Sir William Hamilton at once took Troubridge and Hardy to an informal council at Sir John Acton's house. Nelson wanted an order authorizing him to use the Sicilian ports with more freedom than the French compact permitted—he wanted a sort of informal credential. The King, of course, could not sign such a thing, but Acton might—in his name. There was discussion, hesitation ; but " Captain Troubridge went straight to the point"—just as he went straight at the towering ships of Spain off Cape St. Vincent. Acton was prevailed upon to write an order—not very effectual, but, as it seemed, the best that could be done under the circumstances.

Nelson was very far from satisfied with this result, and describing it to Lord St. Vincent, he wrote—

" Captain Troubridge returned with information, that the French fleet were off Malta on

142 NELSON'S LADY HAMILTON

the 8th, going to attack it, that Naples was at peace with the French republic, therefore could afford us no assistance in ships, but that, under the rose, they would give us the use of their ports, and sincerely wished us well, but did not give me the smallest information of what was, or likely to be, the future destination of the French armaments.'*

The admiral had all the scorn of a man of instant action for the paltry hesitations of those who dared not when they would. It was his temper to say—

" that we would do

We should do when we would; for this * would' changes, And hath abatements and delays as many As there are tongues, are hands, are accidents."

And there were two women in Naples who held the same faith, and who had nothing but contempt for enforced treaties. While the council was taking place at Acton's house, Emma, who guessed how little it was really likely to effect, went in haste to the Queen, who was still in bed. Then ensued one of the dramatic scenes in which Emma delighted. She told the Queen that all would be lost if Nelson's fleet was not freely supplied, and thus enabled to follow the French. She fell on her knees and implored Maria Carolina not to wait on the hesitating action of the King or the Prime Minister, but to act for herself, and give an order in her own name "to all

Governors of the Two Sicilies to receive with hospitality the British fleet to water, victual, and aid them."

It is a little difficult to believe that the Queen of Naples needed all this dramatic persuasion to do what her own interests and inclinations dictated. However, that is how Lady Hamilton tells the story. The Queen consented, the order was written, and Emma departed, all joy and exultation. Troubridge and Hardy had landed at six o'clock in the morning; at eight the council broke up, and Emma joined them. On their way back together to the Palazzo Sessa she told them what she had done, " producing the order, to their astonishment and delight. They embraced me with patriotic joy. * It will/ said the gallant Troubridge, ' cheer to extacy our valiant friend, Nelson. Otherwise we must have gone for Gibraltar/ "

On the same day Lady Hamilton wrote to Nelson—

" MY DEAR ADMIRAL, —I write in a hurry as Captain T. Carrol stays on Monarch. God bless you, and send you victorious, and that I may see you bring back Buonaparte with you. Pray send Captain Hardy out to us, for I shall have a fever with anxiety. The Queen desires me to say everything that's kind, and bids me say with her whole heart and soul she wishes you victory.