Native Seattle (38 page)

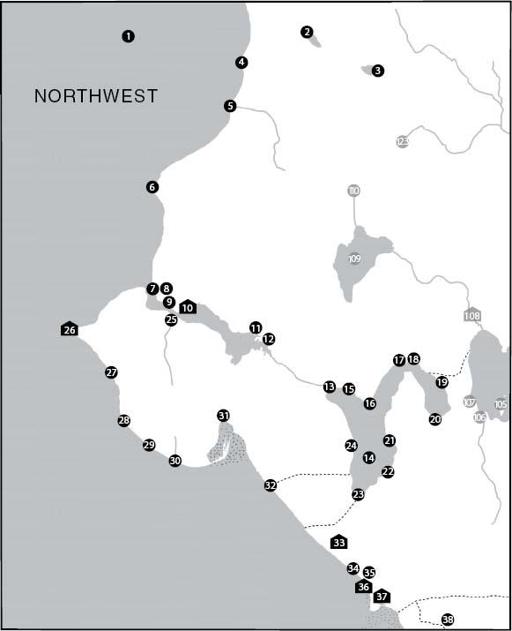

Map 1: Northwest

The four European compass points were not necessarily the most important directions in Puget Sound indigenous life. While indigenous people recognized east and west as the places the sun rose and set, and north and south as places that sent different kinds of weather, orientations such as landward, seaward, downriver, and upriver were just as important, if not more so.

9

Similarly, early settlers on Puget Sound had a sense of direction quite different from that of modern residents. Like indigenous people, the first generation of settlers experienced this region from the water, and so, for them, traveling south to Olympia meant going

up

the Sound, while returning to the north meant going

down

-Sound. Imagine, then, that we are on a landward journey up the Sound, visiting first the territory of the Shilshole people and then moving into the outlying lands and waters of the Duwamish proper.

1

Salt Water

XWulcH

Theodore Winthrop's 1862 travel narrative

The Canoe and the Saddle

used the anglicized form of this word to denote both “Indian Whulgeamish and Yankee Whulgers” who lived along the Sound (correctly using the Whulshootseed change of

cH

to

j

before vowel-initial suffixes). In the century and a half since, this word for Puget Sound, spelled in various ways, has occasionally resurfaced, most notably in the well-known series of guidebooks profiling hikes and other excursions around the Sound published by The Mountaineers.

10

2

Blackcaps on the Sides

cHálqWadee

This place-name refers to the blackcap (

Rubus leucodermis

), a native fruit whose berries and shoots were harvested around the shores of this small lake. Now known as Bitter Lake, Blackcaps on the Sides was also a refuge for the Shilshole people during raids by northern slavers.

3

Calmed Down a Little

seesáhLtub

Haller Lake's original name likely refers to its role as another refuge during slave raids. Projectile points have been found nearby, suggesting that

the lake was also a hunting site. Trails likely connected Calmed Down a Little to other upland sites like 110 and 123 below.

4

Sharp Rocks

XWééXWutSeels

Like many Whulshootseed place-names, this name for the sharp bluffs just south of Spring Beach is straightforward and descriptive, aiding travelers on the Sound in identifying the landmark. Like many other rocks along the coastline, these may have been blasted away.

5

Dropped Down

qWátub

Piper's Creek runs through a deep canyon here in an otherwise gently sloping landscape, which may explain the name. Once the site of large salmon runs, the creek has been restored after decades of neglect.

6

Canoe

Qéélbeed

Most likely, Meadow Point (today's Golden Gardens Park) was used as a storage area for saltwater canoes since at low tide there was not enough water for the people of the nearby Shilshole (today's Salmon Bay) to have access to or from their village.

11

7

Lying Curled Up

CHútqeedud (lit. ‘tip brought up to the head’)

Waterman's informant described this small sandspit at the site of the Shilshole Marina as “lying curled like a pillow” and noted that it was well known as a place for gathering fine clams.

8

Hanging on the Shoulder

KeehLalabud

Like many of the place-names around Seattle and throughout Puget Sound, this one, for the knoll at the north end of the railroad crossing of Salmon Bay, uses language of the body to describe the land.

9

Mouth of Shilshole

sHulsHóólootSeed

The narrow mouth of Salmon Bay takes its name from the indigenous community at entry 10. One of Waterman's informants described the passage through here as “like shoving a thread through a bead.” This statement probably reflects the lack of navigable water; longtime Ballard families report that prior to the building of the locks, one could wade through the water at the mouth of Salmon Bay at low tide.

12

10

Tucked Away Inside

sHulsHóól

This large village was the home of the Shilshoolabsh, or Shilshole people, who had two large longhouses here, each 60 by 120 feet, and an even greater “potlatch house.” Devastating raids by North Coast tribes in the early nineteenth century may explain both the name (which Harrington described as “going way inland”) and the village's location inside Salmon

Bay. Despite settlement by non-Indians, some Shilshole people remained here until the construction of the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks in the early twentieth century, while others became part of the community of Ballard or moved to area reservations. Relatively little is known about this settlement, as construction of the locks destroyed most of it in the 1910s. In the 1920s, however, archaeologist A. G. Colley conducted an excavation of the western part of the site, where the wakes of canal-bound boats had been wearing away several feet of shoreline every year. He found tools made of antler, stone, bone, and even iron.

11

Spirit Canoe Power

butudáqt

The power that resided in this creek allowed indigenous doctors to reach the world of the dead to recover the souls of ailing or troubled people. Doctor Jim, who hung himself on Salmon Bay in 1880, likely was connected with the creek, which by then had been befouled by cattle belonging to Ballard's farmers.

12

Serviceberry

QWulástab

Waterman's “small bush with white flowers and black berries” is a clear reference to serviceberry (

Amelanchier alnifolia

), whose wood was used for gaming pieces and whose berries were eaten either fresh or dried.

13

Outlet

gWáXWap (lit. ‘leak [at] bottom end’)

This was the outlet of a stream, known to settlers as Ross Creek, that emptied Lake Union into Salmon Bay and was the passageway of several runs of salmon (chum, pink, chinook, and coho).

14

Small Lake

XáXu7cHoo (lit. ‘small great-amount-of-water’) This is the diminutive form of the word used to denote Lake Washington (see entry 90), in keeping with the lakes’ relative sizes.

15

Thrashed Water

sCHaxW7álqoo

or

Covered Water

scHooxW7álqoo

People drove fish into this narrow, brushy stream by thrashing the water with sticks. The stream now flows in a pipe somewhere under the streets of the Fremont neighborhood.

16

Extended from the Ridge

sTácHeecH

Now the site of Gas Works Park, this point was described by Waterman's informants as leaning against the slope of the Wallingford neighborhood like a prop used to hold up part of a house.

17

Prairie

báqWab

This was one of several small prairies maintained in what is now Seattle; as such, it was likely an important site for cultivating and gathering roots and other foods that indigenous people propagated through burning and transplanting. The right to dig and burn on prairies typically passed down through women; the rights to this prairie likely belonged to women from entry 10 above and/or entry 108 below. Ancient tools made from obsidian have been found here; the raw material for the tools likely came from central Washington or perhaps as far away as central Oregon.

18

Croaking

waQééQab (lit. ‘doing like a frog’)

Perhaps this small creek on the north side of Portage Bay was known for its amphibious inhabitants, or perhaps it burbled in a way that reminded local people of frogs. The site might also have had religious significance; Frog was a minor spirit power that helped even the most common folk sing during winter ceremonies. A man named Dzakwoos, or “Indian Jim Zackuse,” whose descendants include many members of the modern Snoqualmie Tribe, had a homestead here until the 1880s.

13

19

Lowered Promontory

sKWíTSaqs

The “top” of Lake Union seems an odd place for a “low” name, but the word for this place most likely refers to the point's relationship to the surrounding, and much higher, landscape. Long before white settlers envisioned a canal linking Lake Washington and Lake Union, indigenous people used this corridor to travel between the backcountry and the Sound.

20

Marsh

spáhLaXad

The wetlands on the south shore of Portage Bay must have been a fine place for hunting waterfowl. Chesheeahud, or “Lake Union John,” owned several acres here from at least 1880 until 1906, a fact commemorated in a “pocket park” at the foot of Shelby Street by a plaque and depictions of salmon by an artist of the Puyallup Tribe.

21

Jumping over Driftwood

saxWabábatS (lit. ‘jump over tree trunk’)

The Lake Union shoreline was thick with logs here. A similar place-name, Jumping Down (

saxWsaxWáp

), was used for a Suquamish gaming site on Sinclair Inlet across Puget Sound; that name refers to a contest in which participants vied to see who could jump the farthest off a five-foot-high rock.

14

22

Deep

sTLup

This is a typically no-nonsense description of the place where the steep slope of Capitol Hill descends into the waters of Lake Union.

23

Trail to the Beach

scHákWsHud (lit. ‘the foot end of the beach’)

A trail from Little (or Large) Prairie (entry 33) ended here. An elderly indigenous man named Tsetseguis, a close acquaintance of the David Denny family, lived here with his family in Seattle's early years, when the south end of Lake Union was dominated by Denny's sawmill.

15

24

Deep for Canoes

TLupéél7weehL

Although this name is similar to Deep (entry 22), the difference matters. Such distinctions were critical to correct navigation and the sharing

of information. According to the maps created by the General Land Office in the 1850s, there was a trail near here that skirted the southern slope of Queen Anne Hill on its way to Elliott Bay.

25

Lots of Water

heewáyqW

This creek in the Lawtonwood neighborhood, now known as Kiwanis Creek and the site of a large heron rookery, was a reliable source of freshwater in all seasons.

26

Brush Spread on the Water

paQátSahLcHoo

Excavations for the West Point sewage treatment plant in the 1990s uncovered a history of settlement here that stretched back more than four millennia. Even as landslides, earthquakes, and rising sea levels transformed the point, indigenous people continued to use it to process fish and shellfish. Of particular importance are the trade items found here: petrified wood from the Columbia River, obsidian from the arid interior, and carved stone jewelry from British Columbia, all attesting to far-reaching networks of commerce. Although this deep-time settlement seems to have been forgotten by Waterman's twentieth-century informants, during the nineteenth century the site served as home to dispossessed Duwamish Indians. Waterman was told that the name described the act of pushing or thrusting one's way through brush, or the opening of leaf buds—apt similes for the way the point emerges from the thickly wooded bluffs that overhang it.

16

27

Spring

bóólatS

Harrington collected this name for waters that emerged from the Magnolia Bluffs. Springs like these, arising where water sinks through sand and soil and then reaches nearly impermeable clay, help lubricate the landslides that have destroyed a number of homes near here.

28

Cold Creek

TLóóXWahLqoo (lit. ‘cold freshwater’)

This is a small creek flowing off the Magnolia Bluffs that may have been a reliable source of freshwater for travelers on the Sound. There is some disagreement between Waterman and Harrington regarding

this site and that of entry 30 below; Waterman seems to have confused meanings and words, transposing this name to the other site but giving it that site's meaning. Such discrepancies attest to the imperfect nature of the process by which the two ethnographers gathered their data.

29

Covered by Covering

léépleepahLaxW

and

Rock

CHúTLa

Now known as Four Mile Rock, this massive glacial erratic sits at the foot of Magnolia Bluffs. The meaning of one of its names appears to refer to a story about the boulder. According to oral tradition, a hero named Stakoob once took a huge net woven of cedar and hazel and cast it over this rock from the far side of the Sound. The other name is purely descriptive, like the use of the word for ‘spring’ for various sites.

30

River Otter Creek

QaTLáhLqoo

The intermittent stream in today's Magnolia Park was probably once inhabited by

Lutra canadensis

; it now is mostly covered by a road descending into the park.

31

Mouth along the Side

seeláqWootSeed

When Dr. Henry A. Smith, the man who would eventually pen the first written version of Seeathl's famous speech, moved here in the 1850s, several indigenous families still lived in this place. The slopes above the salt marshes between Smith Cove and Salmon Bay were refuges during slave raids, but a large shell midden excavated nearby in 1913 suggests their importance during times of peace and prosperity as well.