Napoleon in Egypt (58 page)

To what extent Desgenettes actually believed this last claim is not clear. The disease certainly appears to have been contagious, yet not so much as in the more virulent strains of bubonic plague; his main aim remained the avoidance of panic. Either way, his methods were at least accompanied by a containment of the disease for the time being. On April 10 he set up a hospital on the slopes of Mount Carmel to deal with plague victims amongst the 9,000 men now engaged in the siege of Acre. On opening, the hospital had just over 150 patients, and during the following fortnight men were admitted at the rate of around twenty a day, with fatalities running at around four a day. This suggests that men in the besieging army were catching the plague at one or two per hundred per week. Although such figures were not alarming, there is no doubt that both Napoleon and Desgenettes viewed them with concern. Although Napoleon had in mind to attract volunteers and new recruits, as yet the Army of the Orient remained a limited, and decreasing, force.

With their replenished stock of cannonballs, the French guns were soon pounding the walls of Acre once more, this time with a little heavy artillery support. In an attempt to alleviate these barrages, the defenders began making a number of increasingly bold and powerful sorties into the French lines. The sortie on April 8 was a veritable infantry charge, but the French were ready for them. As Napoleon recalled in his memoirs: “800 Turks were killed, amongst whom were 60 Englishmen. The wounded Englishmen were looked after as if they were French, and these prisoners camped in the midst of our army as if they were from Normandy or Picardy; the rivalry of the two nations had disappeared at this great distance from their homeland amidst such barbaric people.”

19

The French and English soldiers had instinctively understood the truth behind their presence here: in essence this was a war being waged by Europeans against the people of the Levant.

XXIII

The Battle of Mount Tabor

A

T

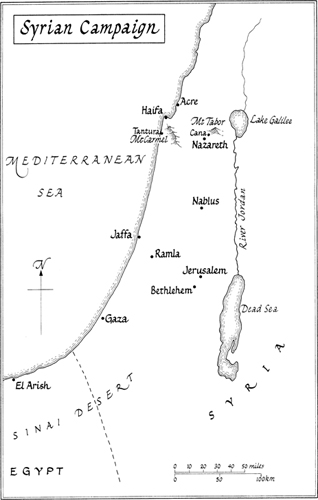

the outset of Napoleon’s invasion of Syria, Djezzar had appealed to the governors of Aleppo and Damascus for support, and as Napoleon marched towards Acre he had continued to monitor the situation to the north, receiving intelligence through the network of Christian communities. According to his memoirs it was now, at the beginning of April, that “secret agents from the north announced the departure of an army from Damascus, adding that it was innumerably large.”

1

Further intelligence reports soon indicated that this army was more than 30,000 strong, and had been joined by 7,000 men from the mountain tribes around Nablus, as well as attracting several thousand other Arab volunteers as it marched south.

Napoleon assessed his own situation: of the original army of 13,000 men who had set out from Egypt on the Syrian campaign, 1,000 had been killed, 1,000 were sick, 2,000 had been left behind to garrison El-Arish, Gaza and Jaffa, and 5,000 men would have to remain at Acre if the siege was to be maintained properly, with the artillery protected from enemy sorties. As he recorded in his memoirs: “This left only 4,000 at Napoleon’s disposal to track down and fight the Army of Damascus and Nablus which was 40,000 strong.”

2

He decided to dispatch three of his generals to investigate: General Vial’s division was sent up the coast towards Tyre, while Murat and Junot were sent inland towards the River Jordan and Lake Galilee with much smaller forces. Bernoyer recalled that: “Generals Murat and Vial returned several days later. In their reports they mentioned having seen nothing which would make them believe in the existence of large troop concentrations.”

3

Napoleon was worried. He felt certain that the enemy was out there, stalking him, and he was caught in the one situation he abhorred: he and his troops in front of Acre were immobile, as well as being vulnerable from the rear. He ordered Junot and Murat back into the field, dispatching Junot towards Nazareth and Murat towards Lake Galilee. On April 8 Junot encountered the enemy. According to Napoleon’s report: “General Junot with 300 men . . . has defeated 3 to 4,000 cavalry, inflicting 5–600 casualties. . . . This was one of the most brilliant military feats.”

4

A day later Napoleon dispatched Kléber with his division of 1,500 infantry to support Junot, and on April 11 Kléber came across 5,000 enemy near Cana, quickly putting them to flight. Four days later Murat heard that a large force of enemy soldiers had crossed the River Jordan north of Lake Galilee. Racing overnight to the scene with just two infantry battalions at his disposal, he arrived at dawn to discover 5,000 enemy cavalry. The men were undaunted and formed up in two battalion squares. They had seen the tents of the enemy camp on the other side of the river, and sensed that victory was liable to result in a rich haul of booty. In the words of the commissary Miot, who was accompanying General Murat: “Soon our troops were no longer marching, they ran and tumbled down the slope.” The enemy was caught completely by surprise: “As there was so little time between our appearance and our charge, this part of the Army of Damascus simply scarpered . . . not even having time to pack up their tents, their ammunition or their supplies.” General Murat and a cavalry detachment set off in pursuit, leaving Miot in command, and telling him to seize everything in the enemy camp:

But the soldiers beat me to it. Filled with joy at their success they scattered throughout the camp to make, with their usual care, a meticulous search of the tents. They found there such quantities of Damascus sweets and cakes, renowned throughout the Orient, that they filled their pockets, their haver sacks. . . . Instead of getting some rest they passed the night in celebration, dancing and singing and delivering the most heart-felt eulogies to the confectioners of Damascus as they gorged on their sweets. . . . At our headquarters we officers dined equally well and just as happily on pastries and delicacies of all kinds.

5

Where raw alcohol had turned men into monsters at Jaffa, sweets turned them all into children.

Napoleon could now be certain that he faced no major threat from the north, but this meant that the main body of the Army of Damascus had now probably outflanked him and crossed the River Jordan south of Lake Galilee, aiming either to attack his positions at Acre from the rear or to reach the sea and cut him off.

Napoleon had been in constant contact with his generals in the field, daily sending them detailed instructions. Kléber in particular had begun to chafe under such close supervision, and now at last saw a chance to make a name for himself on the battlefield for the first time on the Egyptian expedition. The enemy were evidently easy to repulse, and no match for disciplined French troops, no matter how heavily the French were outnumbered. When Kléber reached Nazareth on April 15, he received intelligence that the main body of the Army of Damascus was encamped below Mount Tabor. Taking the precaution of informing his commander-in-chief what he intended to do, but too late for him to countermand this action, Kléber and his division set about making a rapid march undercover of darkness around Mount Tabor, with the aim of launching a surprise attack on the rear of the enemy camp.

Unfortunately, Kléber underestimated both the distance and the terrain, and instead of surprising the enemy camp at two

A.M.

, his tired troops did not reach the plain below Mount Tabor until six

A.M.

, when the sun was already well risen. The element of surprise was lost, the enemy scouts had spotted his columns, and Kléber’s division of 5,000 men found itself confronted by a vast army which was awaiting his arrival. This consisted of 10,000 infantry and 25,000 cavalry, including Djezzar’s cavalry and the Mameluke warriors who had fled Egypt with Ibrahim Bey.

Kléber’s men formed two defensive squares, which were soon being forced to defend themselves from wave after wave of Mameluke cavalry charges. The disciplined soldiers withstood these as best they could, cutting down swaths of Mamelukes in each charge, but for hour after hour the charges continued, and it soon became evident—to both sides—that the French could not last out like this indefinitely. As the sun rose in the sky and the heat intensified, Kléber’s supplies and ammunition began to run low. He realized that his only hope was to hold out until nightfall, and then somehow effect a swift and orderly retreat before the Mamelukes could regroup and give chase. But it quickly became clear to him that they could not last till then, and he was forced to consider a more drastic tactic. It was just possible that he could launch a breakout directly across the plain and attempt to take refuge in Nazareth. But by now things were desperate, as Private Millet recalled:

We had been on the go since six in the morning, and were beginning to run out of ammunition for our rifles as well as ammunition for our stomachs. We had been given so little bread . . . but we had no time to eat even this. And even when we did have time, we were not able to take advantage of it because we were so strung out with thirst and exhaustion that we could not even speak. On top of this we were exposed to the heat of the sun at its height. . . .We were close to a lake, but we had no way to get to it. We had to put up with all this whilst we stood waiting for what seemed like inevitable death.

6

Napoleon takes up the story in his memoirs: “Kléber was lost . . .he sustained and repulsed a great number of charges; but the Turks had taken all the foothills of Mount Tabor and occupied all the surrounding high ground. . . . His position was hopeless, when suddenly a number of soldiers called out: ‘Look over there, it’s the little corporal!’”

*

At first no one believed them. “But the old soldiers who had fought with Napoleon before, and were used to his tactics, took up their cries; they believed they could see in the distance the glint of bayonets.” When word reached Kléber in the middle of his square, he “climbed to a vantage point and pointed his telescope at where they were indicating . . . but he could see nothing; the soldiers themselves believed it to be an illusion, and this glimmer of hope vanished.”

7

In desperation Kléber decided to abandon his artillery and wounded, form his men into a column, and attempt a breakout with every man for himself. Meanwhile it became evident that the enemy was massing for a final grand charge to overrun and slaughter the French. It was now that the miracle took place. Kléber’s soldiers had not in fact been mistaken: Napoleon was indeed coming to their rescue, but for the moment his men were invisible as they moved forward across a slope covered with head-high wild wheat. Napoleon described how next “the commander-in-chief [himself] ordered a square to march up onto an embankment. The heads of these men and their bayonets were soon visible on the battlefield to friend and foe alike.” At the same time he ordered a salvo from his artillery. The Turkish forces were momentarily disconcerted, but were soon reassured by the stirring sight of the advancing Mameluke cavalry of Ibrahim Bey and the tough regiments of the Nablus mountain tribesmen. The Army of Damascus still had the upper hand.

It was now that Napoleon played another master-stroke. Moving his three squares between the enemy forces and their camp, he simultaneously dispatched 300 men in amongst the enemy tents, with orders to set fire to them and make a great show of requisitioning their supplies and their camels. This was a purely psychological tactic, and had an immediate effect on the Turkish forces, who felt themselves cut off. Their ranks were overcome by panic and they began to flee, at first in their hundreds, and then, as the panic spread, in their thousands. Kléber needed no signal, and at once acted in instinctive cohesion with Napoleon, ordering his men to break out—this time in an aggressive charge, rather than a frantic flight for their lives. Their blood was up, and Millet, who took part in the charge, described what happened next:

Remember, we were dying of thirst. Well, our thirst for vengeance had extinguished our thirst for mere water, and instead kindled our thirst for blood. . . . Here we were, wading up to our waists through the water of that lake which only a short time previously we had been craving to drink from. But now we no longer even thought of drinking, only of killing and dyeing the lake red with the blood of those barbarians. Just a short time previously they had been longing to cut off our heads and drown our bodies in that very lake, in which they were now drowning and filling with their bodies.

8

The vast Army of Damascus scattered in their tens of thousands. The cavalry headed into the mountains to the south, whilst the infantry scrambled towards the River Jordan, whose waters had risen due to the recent rains, and whose banks were a quagmire. Several thousand were drowned; French losses, on the other hand, were astonishingly light—if Napoleon is to be believed: “Kléber lost 250–300 men killed or wounded, while the columns of the commander-in-chief lost 3–4 men.”

9