Napoleon in Egypt (53 page)

Napoleon was convinced that all this could take place “regardless of the loss of his fleet,” for it was to be an overland expedition in the footsteps of Alexander the Great; indeed, preparations for this “march on India” had already been set in motion. According to Napoleon, “He had intelligence from Persia, and was assured that the Shah would not oppose the passage of the French army through Basra, Shiraz and Mekran.”

†

13

All this may appear to be little more than the grandiloquent dream of hindsight, but as we have seen (and shall see), there is a wealth of evidence to support the fact that Napoleon believed he could actually achieve this. Several of his generals mention in their memoirs his preparations for an invasion of India, echoing the figures and dates that appear above, and Bourrienne, although admittedly not always reliable, appears to confirm these preparations with his claim that even “before taking the decision to attack the avant-garde of the Turks in the valleys of Syria, he knew for a fact . . . through agents sent to the spot that the Shah of Persia would consent, in return for a payment made in advance, to let him establish at designated locations military depots of supplies and equipment.”

14

It now becomes clear why Napoleon was leaving behind so few forces to defend Egypt: he was gambling his all on this “Syrian campaign.” Indeed, he was arguably playing for bigger stakes than he would ever play for in his entire life. All this would account for why he also brought with him so many members of the Institute, as well as a large number of lesser savants. These included the inevitable Monge and Berthollet (who would again be allowed to travel by carriage), along with mathematicians, physicists, biologists and Orientalists—so many, in fact, that a notice appeared in

La Décade

to the effect that for the time being there would be no further meetings of the Institute. Several of the savants were to undertake important tasks. The geographer Jacotin was to go to work “surveying on foot and by compass the distance covered on each day’s march and the positions of the army’s pitched camps, and in this way putting together a map of the invaded territory”;

15

while the naturalist Savigny would be “employing his time collecting any insects he found in the desert.” The indefatigable Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, who had already completed his survey of the fauna of the delta, would seek to trap any lizards, snakes and quadrupeds he came across, and bring them back for the Institute’s menagerie.

In this too, Napoleon’s Syrian expedition would be following the example of Alexander the Great, who sent back to Aristotle in Greece examples of flora and fauna which his expedition found on the way to India. The main difference here was that Napoleon took his savants with him; besides describing and collecting what they found, they would also be purveyors of French culture, of European science and knowledge, as well as being founder members of further Institutes to be established in the Orient.

Other indications that the Syrian expedition was intended as the first step in a much grander project can be seen in the fact that Napoleon insisted upon bringing along a number of Egyptian notables. These included the Turkish official he had nominated as Emir el-Hadj in place of Murad Bey, as well as the

cadi

, the high judge of Cairo, and fifteen sheiks, “each of whom brought along three tents which were fitted out with every Asiatic luxury.”

16

These notables were intended to show that Napoleon had the support of the Egyptian people, and was also a friend of Islam. They would prove useful as ambassadors, and might be helpful in any negotiations with Arabic or Islamic leaders. More important, they could be instrumental in the establishing of a French regime that took account of the religious susceptibilities of the local inhabitants, much as Napoleon liked to think he had done in Egypt.

El-Djabarti too noticed that Napoleon’s expedition seemed to be taking along more than was required for a simple punitive campaign against Djezzar. “The soldiers took with them a great deal of luggage, including beds, mattresses, carpets, as well as large tents for their wives and the White, Black and Abyssinian slaves they had taken from the mansions of the Mamelukes. All these women had adopted French costume.”

17

Officers were evidently permitted to bring along their wives, or such mistresses as they had acquired in Egypt. There was however one notable exception: Pauline Fourès was left behind in her pavilion in the grounds of Elfi Bey’s palace. Napoleon seemingly wished for no distraction whilst he set about fulfilling his great ambition. Far from being just a simple campaign, this looked much more like an entire expedition in itself.

XXI

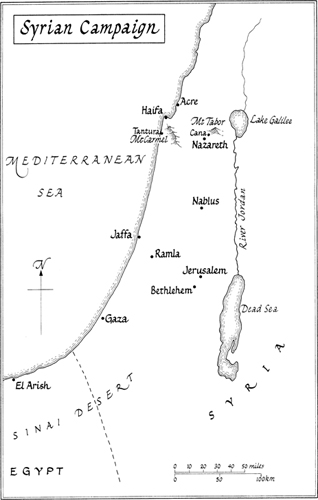

The Syrian Campaign

L

EAVING

General Dugua in charge, Napoleon set off from Cairo with the divisions commanded by Bon and Lannes on February 10, 1799, intending to catch up with the divisions of Reynier and Kléber, which were already setting off from Katia for El-Arish. Kléber, once again in charge of a field division, was back to his formidable ebullient self, an indication of which can be judged from Nicholas Turc’s description of him as “a man of high stature, an imposing presence and a voice of thunder.”

1

In Napoleon’s latest report to the Directory, dictated to Bourrienne just an hour before he set off, he confidently predicted, “By the time you read this letter, it is possible I will be standing at the ruins of Solomon’s Temple [i.e., in Jerusalem]”; but to begin with, he told them, “we must spend nine days crossing the desert devoid of water or vegetation.”

2

Yet despite his divisions being accompanied by no fewer than 3,000 package camels and 3,000 laden mules, the expedition seems to have started out ill-prepared. Part of the blame for this doubtless lay with Napoleon’s chief of staff, General Berthier, who was still pining for his beloved Countess Visconti back in Italy. Initially, this had been a source of some ribaldry to Napoleon and his staff, but of late the forty-five-year-old Berthier had gone into such a decline that Napoleon had given him permission to return to Europe on the first available boat. On arriving at Alexandria Berthier had been overcome by conscience and hurried to catch up with Napoleon, but by now the damage had been done: a full-scale military campaign is best not organized by a lovesick chief of staff.

The crossing of the Sinai desert north to El-Arish proved a disorganized shambles. According to Bourrienne, who traveled at Napoleon’s side: “The exhaustion of the desert and the lack of water provoked violent murmurings amongst the soldiers. When an officer passed beside the men on his horse they would give vent to their discontent . . . [with] the most bitter sarcasms . . . their more violent remarks being against the republic, and against the savants who were considered responsible for the [entire Egyptian] expedition in the first place.”

3

Those marching east from the coastal cities fared differently, but little better. Private Millet, who had recovered from the plague and was with the contingent marching from Damietta, recalled: “While we marched close to the sea, we had to weather it out through heavy rain. . . . The nights were very cold, the days were very hot.”

*

4

General Damas noted in his journal:

The cold weather mixed with rain has lasted for 15–20 days, and according to the locals will last another month yet in this region, and will be worse in Syria. This holds out the prospect of some arduous marches across the desert and makes one fear that there will be outbreaks of sickness amongst the soldiers, who are badly equipped for the weather and the terrain; they are lightly dressed in tunics, trousers and cloaks, all of linen, which are insufficient to protect them against the cold nights and the frequent rain.

5

In a classic military mix-up, the men had by now been issued with new lightweight uniforms, manufactured in Cairo and suitable for the Egyptian climate, but not for that prevailing along the Mediterranean coast in midwinter. The animals fared little better. Captain Doguereau of the cavalry was soon complaining: “Our horses went three days without eating anything but date palm leaves. . . . Our camels had to search for themselves for victuals. They were given nothing to eat and we feared we were going to see them perish without being able to replace them.”

6

All this would appear to be something more than the teething troubles that beset any large-scale logistic operation, and the blame should not be placed entirely on Berthier’s shoulders. The root of the problem was almost certainly financial. By this stage Controller-General Poussielgue was finding it extremely difficult to balance the French administration’s budget. Tax revenue was proving scarce, and in order not to let the soldiers’ pay slip further into arrears, he had been forced to borrow against generous estimates of the tax receipts for next season’s harvests, whose quantities were of course still uncertain.

The Syrian expedition had got off to an inauspicious start, and would show no signs of an early improvement. After Napoleon left Katia, he was annoyed to learn that El-Arish had not yet been taken. When Kléber and Reynier had arrived just a week previously, they had been surprised to discover that the reinforced garrison fort containing 1,800 Turks and Mamelukes had been further reinforced by 1,500 tough Albanian and Moroccan infantry swiftly dispatched from Acre by Djezzar. They had no alternative but to lay siege to it. According to Napoleon, after he heard this news, “he got on his camel, rode through the night, and arrived at El Arish at daybreak on 15 February.”

7

During that very night, Reynier had launched a surprise attack on the enemy camp, catching most of its inmates asleep. Four hundred or so of the enemy had been killed and around 900 taken prisoner. According to Napoleon’s report of the encounter: “Reynier lost 250 killed or wounded. The army grumbled about this, reproaching him for such losses. These reproaches were unjust; the general acted with initiative, just as the circumstances demanded.”

8

The enemy camp may have fallen, but this was in fact outside the walls of the fort, so the siege continued.

The situation quickly descended into farce. The besieging French soon began running out of what little food they had, and the eyewitness Malus recalled: “We were eating camels, horses and donkeys. We were reduced to the last extremity.”

9

A major woke up one morning to discover that during the night his men had eaten his horse. Meanwhile inside the fort the Turkish and Mameluke troops had all the food they needed, having recently been supplied by sea with a large quantity of provisions by a Greek merchant from Damietta, whose wares consisted largely of goods pilfered from French army stores and sold on the black market. However, the besieged garrison could not eat throughout the day, as the holy month of Ramadan had just begun and they were obliged to observe a fast between sunrise and sunset. No one now slept during the night, as those under siege cooked over their fires, and the mouth-watering smells wafted out over the vast number of starving besiegers.

After three days, Napoleon’s patience was at an end. He sent in an emissary under a white flag to offer surrender terms, but the Turkish commandant proved obdurate and negotiations quickly broke down. The French artillery now formed a ring around the fort and began a heavy bombardment. Indeed, this was so heavy and the fort so small that several cannonballs flew right over it and landed amongst the French artillery on the far side. Unfortunately, this artillery consisted only of light field guns, as all the larger siege guns remained at Damietta, waiting to be shipped up the coast to Acre. In the end it took the French artillery all day before a small breach was opened in the walls at one of the towers. Undercover of darkness, the French sappers attempted to move in close and detonate a larger breach, but as Major Detroye noted: “The tower under attack was soon demolished to half its height. The enemy showed extraordinary bravery, working on repairs and firing from the tower in the midst of our cannon balls and shells.”

10

The Syrian campaign was evidently going to involve a tougher enemy than the previous French battles against the Mamelukes.

At noon on the following day, Napoleon dispatched a further emissary, reminding the commandant that under the traditional rules of war, once the walls of a place under siege were breached those inside were required to surrender, or they could be slaughtered to the last man. This time the commandant decided to surrender. Most of the Mameluke prisoners were simply relieved of their valuables, disarmed and sent back to Egypt, but the other defenders received very different treatment. According to the official reports by Napoleon and his newly returned chief of staff Berthier, the surrendering garrison filed out, and were made to promise in the presence of the Koran that they would not take up arms against the French for the space of a year. They were then escorted almost twenty miles into the desert and ordered to march east to Baghdad. Malus gives the lie to this fairy tale: after the prisoners had sworn their oath and were permitted to march away on parole, “they were surrounded by Bon’s division, then dispersed thoughout the different divisions of the French army, where they were pressganged into serving with us.” But he goes on to reveal, “They all deserted later, as soon as they found the opportunity.”

11