Nabokov in America (31 page)

Read Nabokov in America Online

Authors: Robert Roper

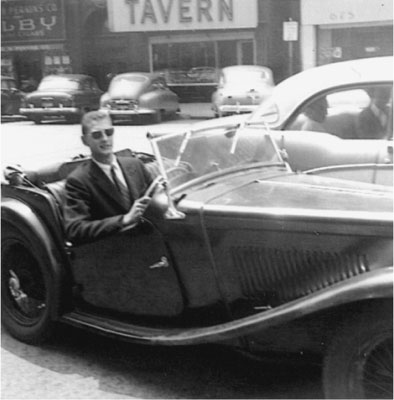

Dmitri, mid-1950s, in the first of two MG TCs

Melville throws many types of rhetoric at the world. There is Puritan sermon, scientific treatise, legal brief, and Miltonian thunder in his book, not to mention comedy, drama, and classical argument. His use of a rough sort of Shakespeare-speak achieves an earnestness beyond parody:

THE OLD MANXMAN

Sir, I mistrust it

78

; this line looks far gone,

Long heat and wet have spoiled it.

AHAB

Twill hold,

Old

gentleman. Long heat and wet, have they

Spoiled thee? Thou seem’st to hold. Or, truer

Perhaps, life holds thee; not thou it.

OLD MANXMAN

I hold

The spool, sir. But just as my captain says.

With these gray hairs of mine ’tis not worth while

Disputing, ‘specially with a superior, who’ll

Ne’er confess.

AHAB

What’s that? There now’s a patched

Professor in Queen Nature’s granite-founded

College; but methinks he’s too subservient. Where

Wert thou born?

OLD MANXMAN

In the little rocky Isle of Man, sir.

AHAB

Excellent! Thou’st hit the world by that.

Nabokov’s

parodies

79

are more sarcastic. But both novels record a failure to tame the world with words. They are incommensurate, words and the world: the analogy may be to Job’s feeble, pious prayers as against the voice out of the whirlwind, or the whirlwind itself.

Nabokov does not attempt Shakespeare-speak, but

Lolita

is spotted with Shakespearean allusions, and a device central to the novel is borrowed from

Hamlet

and

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

: the play within a play.

Boyd shows

80

that the novel’s play, a work by Clare Quilty, Humbert’s nemesis, in which Lolita wins a part, is unpersuasive; Quilty describes events that he could not possibly have known about, nor could he have known that Humbert would bring his captive child to the New England town of Beardsley, there to enroll her in a school that happens to be putting on the play in question. But never mind.

Lolita

’s story of a selfish monomaniac imposing a scheme on others that leads to general doom evokes Captain Ahab’s in its essence. Faulkner, whose Sutpen saga grows from a similar root, said of

Moby-Dick

,

The

Greek-like simplicity

81

of it: a man of forceful character driven by his sombre nature and his bleak heritage, bent on his own destruction and dragging his immediate world down with him with a despotic and utter disregard of them as individuals … a sort of Golgotha of the heart become immutable as bronze in the sonority of its plunging ruin; all against the grave and tragic rhythm of the earth in its most timeless phase: the sea.

What’s missing from

Moby-Dick

is an enchanting child. But

there

82

is

a child, and he

is

enchanting. Ahab’s grimness is tempered by his love for the ship’s boy Pip, who loses his mind from fear after being left awhile afloat in the open ocean. Like Lear’s fool, Pip speaks cracked wisdom, and Ahab adopts him, explaining, “

Thou touchest

83

my inmost centre, boy; thou art tied to me by cords woven of my heart-strings.”

One of

three blacks

84

(one African, two African American) aboard the ship of all men, Pip wonderingly strokes the captain’s hand, musing,

What’s this? here’s

velvet shark-skin

85

… . Ah, now, had poor Pip but felt so kind a thing as this, perhaps he had ne’er been lost! This seems to me, sir, as a man-rope; something that weak souls may hold by. Oh, sir, let old Perth [ship’s blacksmith] now come and rivet these two hands together; the black one with the white, for I will not let this go.

Ahab, along with everyone but Ishmael, will not escape his fate by this turn to fatherly love. But the novel escapes some of its grimness thereby. Ahab has set his course and will follow it, but his diabolical arrogance partly drops away. The grimness of a story of mechanical, three-times-a-day rape of a child was the great challenge to Nabokov, and he wrapped it in brilliant wordplay and other diversions, but finally there it was, unbearably, unmistakably. Like Melville, whose Greek-like tragedy was all too plainly built and dark, Nabokov added colors of the heart, facetiously or not, to his story, especially to its final act. We see the monster coming to love, treasuring the worn seventeen-year-old girl with her “adult, rope-veined narrow hands” when Humbert visits her in Coalmont, and his untrustworthy words need to be trusted, so that we, his readers, can feel the deepest pity stir in us:

Unless it can be proven

86

to me … that in the infinite run it does not matter a jot that a North American girl-child named Dolores Haze had been deprived of her childhood by a maniac, unless this can be proven (and if it can, then life is a joke), I see nothing for the treatment of my misery but the melancholy … palliative of articulate art.

*

Americans have historically spoken, thought, and written out of any number of texts, but especially religious ones, and most especially the Bible. A masterful piece of American rhetoric like the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech is continually allusive but unpedantic. The density of its culture may be hidden to American ears yet is a prime source of its power. Among the sources melded and worn plainly but veiled by familiarity in that speech are the American Negro spiritual (“Free at last”), the Gettysburg Address, the Declaration of Independence, “My Country, ’Tis of Thee,” Langston Hughes’s “Let America Be America Again,” Exodus, Galatians, Isaiah, Amos,

Richard III

, “This Land Is Your Land,” and W. E. B. Du Bois’s

Autobiography

(“this is a wonderful America, which the founding fathers dreamed”).

One

of Nabokov’s favorite spots to stay, with an inexpensive roof over his head, was Afton, Wyoming, a small Mormon town along the meandering Salt River. Here Vladimir and Véra spent some weeks in ’52 and ’56, in a motor court on the edge of town called the Corral Log Motel. East of town rises the Salt River Range, part of a national forest. In a chatty entomological paper called “Butterfly Collecting in

Wyoming, 1952

1

,” Nabokov remembered “spending most of August in collecting around the altogether enchanting little town of Afton,” which was reached by a paved road close to the Idaho state line.

The Nabokovs had their own unit with bath.

Gathered around a central space

2

, like encircling Conestoga wagons, the cabins were built in Broadaxe Hewn Log style, with compound dovetail corners (each log end extending beyond the meeting of walls). The logs were debarked and varnished, the chinks filled with mortar and covered with battens. Several creeks flow west from the mountains near Afton. Nabokov’s method was to follow the creeks upstream, taking specimens in the riparian brush. “

In early August

3

,” he wrote in his paper, “the trails in Bridger National Forest were covered at every damp spot with millions of

N. californica

Boisd. in tippling groups of four hundred and more, and countless individuals were drifting in a steady stream along every canyon.”

He had been working on

Lolita

at that point for three years. Most of that work had been preparatory, what he called “

palpating

4

in my mind,” with much note-taking. During his semester at Harvard in spring ’52 he might have

begun writing

5

a draft, but during that summer he in fact

wrote little

6

or nothing.

Corral Log Motel, Afton, Wyoming

He

enjoyed his usual vacation bloom of health. The years of work on the book were, on the whole, a time of health crises: dental dramas, and in ’50 a recurrence of intercostal neuralgia, a painful inflammation of the nerves of the ribs, which can make breathing torturous. He told Wilson,

I

spent almost two weeks

7

in a hospital and have been howling and writhing since the end of March when the influenza I caught at that somewhat dingy [

New Yorker

] party tapered to the atrocious point of intercostal neuralgia, the symptoms of which, the wracking, unceasing pain and panic, mimic diseases of the heart and kidney, so that for days on end I was experimented upon by doctors… . I am not quite well yet, had a little relapse to-day and am still in bed, at home.

When at home he was able to write undisturbed. Véra delivered his lectures in his stead, and other

annoying duties

8

temporarily dropped away.

Dmitri, who had faltered at Harvard—his freshman year “began

tempestuously

9

,” Nabokov told Wilson—soon righted himself. He was distractable but able “to

focus briefly

10

on a page [and have] it register photographically,” he later wrote of himself, and in the end he graduated with honors, to his parents’ delight. Nabokov told his sister that Dmitri was “interested, in

the following order

11

, in: mountain climbing, girls, music, track, tennis, and his studies.” Vladimir’s semesters at Harvard were for purposes of close monitoring as well as research; Véra

and he imposed a regime whereby Dmitri had to earn his own pocket money, and he worked as a dog walker, a mailman in Harvard Yard, and a “

partner for tennis

12

and French conversation to an odd, ruddy-faced Bostonian bachelor” who picked him up in a Jaguar.

He joined the Harvard Mountaineering Club. This organization has been

associated with ascents

13

of imposing mountains since its founding, in 1924, and Dmitri came to the club during a postwar golden age. Harvard

climbers went to

14

Alaska, Peru, Antarctica, the Himalaya, the Canadian Rockies, and western China. (A peak in the Amne Machin Range was rumored to be taller than Everest.) The most influential American climbers of the fifties were Harvard men. They included Charles Houston, leader of the 1953 K2 expedition, on which Art Gilkey died; Ad Carter, editor of the

American Alpine Journal

, the world’s leading mountaineering journal; and Brad Washburn, whose aerial photos of Mount McKinley and other peaks made accurate mapping possible. Dmitri

did not climb on a rope with

15

them, but he rubbed shoulders with these men, and he hungrily assimilated the club ethos, moving from beginner to leader on first ascents. In ’54 he

published an article

16

in the

Alpine Journal

, “Mt. Robson from the East,” describing a climb of the East Face of the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies, a two-day ascent that included sleeping out in a crevasse. On this same trip he led the

first ascent of Gibraltar

17

Mountain, in the Canadian Selkirk Range. His team drove into Canada in “

an elderly Packard

18

hearse whose motor we lovingly rebuilt … and which we equipped with bunks” and war-surplus B-25 tires.

“I

doubt if we shall ever

19

get used to it,” Nabokov wrote his sister Elena, referring to his son’s risk taking. Several Harvard

climbers died

20

. Dmitri was mad for speed as well as summits, and by September ’53 he had run “

his third car

21

into the ground,” his father reported, “and is getting ready to buy a used plane.” He “worked building highways in Oregon [in the summer of ’53] and handling a gigantic truck,” while his father and mother, traveling here and there to rendezvous with him,

often worried

22

.

For a while they lodged in the town of

Ashland

23

, Oregon. Like Afton, and like Estes Park and Telluride, Ashland sits in the lee of mountains, in this case the Siskiyous, with nearby streams, lakes, and marshy meadows. (“There is

no greater pleasure

24

in life than exploring … some alpine bog,” Vladimir told Wilson.) The town had a commercial district and

modest wooden houses

25

for rent. Ashland in the summer is full of blooming roses. Here Nabokov dictated much of

Lolita

in its final form.

Upon returning to Ithaca that September he told Katharine White that he had “

more or less completed” his “enormous, mysterious, heartbreaking novel,” a novel requiring “five years of monstrous misgivings and diabolical labors.” It had cast on him an “intolerable spell” and was “a great and coily thing

26

[with] no precedent in literature. In none of its parts will it be suitable” for her magazine.