Nabokov in America (26 page)

Read Nabokov in America Online

Authors: Robert Roper

Postcard sent by Nabokov to Wilson from Wyoming, summer 1949

He was not a hack, warmly pandering. He was writing the book that had come to him that he felt the need to write. While he wrote, his Russian memoir appeared, and despite its rollout in the

New Yorker

and other magazines,

Speak, Memory

was another “dismal flop” in the market, bringing him “fame but

little money

52

,” he told his sister.

To reach

53

America’s mythic mass audience might have begun to seem impossible.

America contributed a cathexis as well. In France in the fall of ’39, when he wrote

The Enchanter

and then read it one night to four friends, a pedophile’s story, complete with description of desperate flight with child, did not live on the page. In America, the resonance was different. Like the author of a story about bulls and capes who changes the setting to Spain, Nabokov inherited a stage, and the sad, abbreviated flight in

The Enchanter

became as large as he was able to make it. Mark Twain, another writer he hardly deigned to notice (“

in the matter of

54

the American Academy …,” he wrote Wilson at about this time, “I know nothing whatsoever … and at first confused [the Academy] with a Mark Twain horror that almost obtained my name”), was the acknowledged master of

that

literary domain. Twain wrote within a tradition of slave narratives, as well as the genre of Indian abduction accounts, stories of frontier settlers taken and carried away. The white captives were often female. The first popular book of the kind was Mary Rowlandson’s

The Sovereignty and Goodness of God

, about a Massachusetts wife taken by Narragansett Indians during King Philip’s War (1675–78). It became the

first American bestseller

55

and appeared in

thirty editions

56

over the next 150 years. By 1800,

seven hundred

57

captivity narratives had been published, and early American novelists, such as Susanna Rowson and Charles Brockden Brown, worked the theme ingeniously. Sexual exploitation was always a subtext. Nabokov’s interest in such accounts—at any rate, his acquaintance with the genre—follows from his reading of Pushkin, who in 1836 wrote a long,

enthusiastic review

58

of the French translation of a book called

The Narrative of John Tanner

(a.k.a.

The Falcon: A Narrative of the Captivity and Adventures of John Tanner during Thirty Years Residence among the Indians in the Interior of North America

). Writing in a Russian journal he co-edited, Pushkin told the story of an American child abducted by Shawnee at age nine, then sold to an Ottawwaw woman whose son had died. The “absolute

artlessness

59

and humble simplicity of the narrative vouch for its truth,” Pushkin said, and he liked especially the description of an animal called “the

moose

60

,” which he identified as “the American reindeer.”

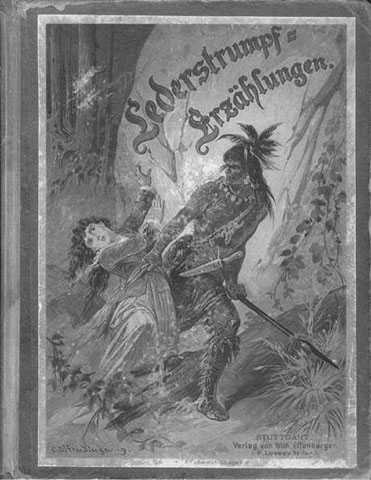

The Leatherstocking Tales, cover art by C. Offterdinger

Nabokov’s

immersion in Pushkin was lifelong but

reached its height

61

in the years when he worked on

Lolita

, when he was also translating

Eugene Onegin

. He might have read Fenimore Cooper’s

The Last of the Mohicans

, the best of the Leatherstocking Tales, as

Pushkin had done

62

; like Mayne Reid, who wrote a novel called

The White Squaw

(1868), Cooper embroidered the female abduction theme. Probably Nabokov’s path to channeling this mode is best explained, however, not

by examining literary influences but by invoking the imponderables of inspiration. As quick as he was to pick up American slang, or to become knowing about American locales, he was intuitive and subtle in knowing

what tale to tell

63

—a very old tale, as it happened, provocative, formally simple, and outward-facing, toward the American vastness.

Summer of ’49, he traveled to Salt Lake City to take part in a writers’ conference. His fellow panelists included Wallace Stegner, the Western novelist best known for

The Big Rock Candy Mountain

(1943), and Dr. Seuss (Ted Geisel), former political cartoonist and author of

And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street

(1937) and

Bartholomew and the Oobleck

(1949). John Crowe Ransom, editor of the

Kenyon Review

, was also there; Nabokov

found him smart

64

and likable, and he was taken also with Dr. Seuss. The Nabokovs stayed at a sorority house on the University of Utah campus. They had driven west in their own car, a ’46 Oldsmobile, their first cross-country drive since the trip to Stanford. Véra had taken lessons in Ithaca. She was nervous about driving across herself, so they hired one of Nabokov’s Cornell students, a nineteen-year-old named Richard

Buxbaum

65

, to spell her at the wheel.

Buxbaum was brought along also to keep Dmitri company. The boys spent time talking about girls. At the conference, each proposed to pick out a girl “to have for the duration” of their stay in Salt Lake. Buxbaum drove more than Véra did, with Dmitri or Véra beside him in the front seat; Nabokov was always in back with his notebook. The route they took was direct,

resembling the route

66

taken by Humbert Humbert on his second long journey with Lolita, from the Northeast across Ohio, then “the three states beginning with ‘I,’ ” then Nebraska—“

ah, that first whiff

67

of the West!” Humbert enthuses, his ultimate goal being California, where he intends to spirit Lolita across the Mexico border. The

nonfictional travelers

68

stayed at motels, as do the fictional ones; the boys shared a room, the grown-ups another—the grown-ups, Buxbaum noted, preferring rooms with separate beds.

“We traveled very leisurely,” it says in the novel, and Nabokov and his party took eleven days to reach Salt Lake, a moderate pace at the time. Lolita “passionately desired to see the Ceremonial Dances” along the Continental Divide, Native American dances; unbeknownst to Humbert, she plans to escape there, into the custody of Quilty, her other pedophile suitor. They are welcomed to motels by signs that read,

“

We wish you

69

to feel at home while here. All equipment was carefully checked upon your arrival. Your license number is on record here. Use hot water sparingly. We reserve the right to eject without notice any objectionable person. Do not throw waste material of any kind in the toilet bowl. Thank you… . We consider our guests the Finest People of the World.”

Humbert recalled paying “ten for twins,” that “flies queued outside at the screenless door and … scrambled in,” that “the ashes of our predecessors still lingered in the ashtrays” and “

a woman’s hair

70

lay on the pillow.” Fictional ’49 probably resembled real, and vice versa; Humbert registers a contemporary change in roadside architecture, that “

commercial fashion

71

was [for] cabins to fuse and gradually form [a] caravansary, and … a second story was added, and a lobby grew in, and cars were removed to a communal garage.”

Buxbaum found Véra fascinating. She was a graceful woman with “

beautiful bones

72

—a lovely person, lovely.” Nabokov reminded him of other Eastern European gentlemen he had known, with savoir faire and languages. (Buxbaum’s family were German-speaking Jews who had arrived in ’39. His father was a doctor in Canandaigua, New York; he worked at a Mohawk reservation on the Quebec border.)

The conference over, the group headed for the Tetons, where Nabokov had some collecting he wanted to do. In advance, he had

conferred with Alexander B. Klots

73

, a lepidopterist at the AMNH; Klots sought to allay Véra’s fears of grizzly bear encounters, warning, though, that moose could be aggressive and “I would rather

meet ten bears

74

with cubs.”

South of the Tetons

75

, where the Hoback River joins the Snake, they traveled east and stayed at the Battle Mountain Ranch, where Nabokov busily collected. They stayed longer, for more than a month, at the Teton Pass Ranch, in Wilson, Wyoming, seven miles west of Jackson and south of the high mountains. Buxbaum left them here, to hitchhike back east, but first the two boys tried to climb Disappointment Peak, a subsidiary summit of the Grand Teton. They failed but had

an adventure

76

. They wore tennis shoes and began climbing the shattered rock of the mountain without mountaineering equipment. Somewhere short of the nearly twelve-thousand-foot summit, they were afraid to climb any higher but faced a jump from one ledge to a lower one in order to descend, with a misstep promising death. It took two hours for one of them to summon the nerve, the other then following.

Disappointment Peak, Teton Range, Wyoming

Buxbaum

sensed Nabokov’s anger when they emerged from the woods several hours late. Nabokov seethed but did not voice his anger. Both parents had been out of their minds with worry.

Nabokov wrote Wilson on August 18, “We have had some wonderful adventures … and are driving back next week. I have

lost many pounds

77

and found many butterflies.” They crossed into Canada on the way back, traveling just north of the Great Lakes. The previous spring, after a car trip with Véra, he had described to Wilson the “lovely

soft-bosomed

78

scenery” they saw between Ithaca and Manhattan; his wife had driven him “beautifully,” he said. They were Americans now, able to

go where they wanted

79

in their own car, when they wanted. Their automobiles—a 1940 Plymouth, never in very good shape; the Oldsmobile; a new green Buick Special bought in ’54; an “

amazing white [Chevrolet] Impala

80

” rented while they lived briefly in Los Angeles—became markers of periods in their lives and of their modest financial ascent. The Olds was the

Lolita

car, the one Véra parked in the shade of roadside trees when Vladimir wanted a quiet, upholstered place to write. The famous photo of him writing in a car, taken by Carl Mydans of

Life

, dates from ’58 and

is a staging

81

; the car is the two-door Buick, not the legendary Olds, and the location is a roadside near Ithaca.

During

their next trip west, in 1951, Nabokov was still constantly taking notes. His American

researches were extensive

1

. They bespeak a desire to get things right and also an anxiety about his subject; he recorded information on the habits and physiques of pubescent American girls, on the average age of menstruation onset, on attitudinal changes, on the proper method of inserting an

enema tip

2

into a rectum. He collected

girlish slang

3

from teen magazines, his Russianness, notwithstanding his long acquaintance with formal English, helping such phrases as “It’s a sketch” or “She was loads of fun” to emerge from colloquial invisibility.