My Life So Far (84 page)

Then there was fly-fishing. The sport is so hard to master; my week at the Orvis Fly Fishing School notwithstanding, I often ended a day in despair, throwing myself screaming onto the banks. But since Ted was spending an average of a hundred days a year wetting a line, I felt I had to get good at it.

Fly-fishing is endlessly humbling. Every time I thought I’d graduated to the next level, Ted would buy a new ranch with harder-, faster-flowing water and smarter, bigger fish. But I learned why the sport is so important to him: It requires total Zenlike focus, and it is silent. You won’t catch much if you don’t want to be there or if you have other things on your mind. For Ted—who doesn’t handle stress well and is hard of hearing—fly-fishing is a balm. The sport requires you to be fully tuned in to every aspect of the natural world around you: the insects that may (or may not) be rising over the water, the position of the sun, where your shadow is being cast. Then there’s the underwater world you have to try to penetrate.

There’s something sensual about this world. In his book

Fly Fishing Through the Midlife Crisis,

Howell Raines describes its magic this way: “Imagine that cells scattered throughout the bone marrow—and particularly in the area of the elbows—are having subtle but prolonged orgasms and sending out little neural whispers about these events.” Maybe

that’s

why Ted loves the sport so much!

W

ithin a few years Ted had four ranches in Montana within two-hour drives of one another, each offering a different fishing experience. It was not unusual in the summers for us to have breakfast and early morning fishing at one, then drive two hours to another, where we’d have lunch and afternoon fishing, then drive to the third for dinner and evening fishing. My dear friend Karen Averitt, who had run one of my Workout studios in California and then my health spa at Laurel Springs Ranch (and then married Jim, my ranch hand/musician), had now, at my urging, moved with her family to Montana to cook and look after Ted’s houses. For those long summer months I marveled at how Karen managed to pack and unpack coolers, load them into her truck, and have the three meals ready in three different places—all in one day. It’s still going on, I might add. When Ted and I separated, Karen came to me and said, “Jane, you know I love you and always will, but Ted needs me more.” No kidding!

By the way, if you eat at one of Ted’s Montana Grills around the country (which I strongly recommend), you’ll see items like Karen’s “Flyin’ D” Bison Chili on the menu.

S

ome of the most precious memories I have of my time with Ted are those of the predawn hours, rowing with our dogs out to a duck blind in the ACE Basin of South Carolina, past the falling-down old rice mill and cabins from the days of rice plantations and slavery; waiting in the blind for the sun to come up; listening to the dogs’ teeth chatter, partly from cold and partly from excitement; the sounds of the forest coming to life behind us; the gray mists lingering in the tall pines; and the pale pinks and mauves of dawn reflected in the shallow marsh waters. I remember during morning quail hunts in the woods at Avalon how the sun shone through the beads of dew that hung on spiderwebs, turning them into glimmering tiaras and the sulphur butterflies fanning the velvet air and alighting briefly on spires of lespedeza; Ted rowing me slowly through the Tai Tai canal through the swamps at Hope Plantation in South Carolina’s ACE Basin, where the swampy, brackish water was so dark and still that in my photographs I couldn’t tell which was real and which was the reflection of reality; Ted knowing that the orange streak that had just gone by was a summer tanager; Ted knowing where the pair of bald eagles was nesting (he had a pair on every property, it seemed).

It was as though all the critters knew that the land was in the hands of someone who cared about them, so they came. A pair of sandhill cranes made their nest on an island Ted had created in the lake in front of our house on the Flying D Ranch. One morning we woke to a shrill cry and immediately Ted sat up in bed and said, “It’s the crane! Her egg has hatched.” He was right, and I loved him for his knowing. He knew his animals, especially his birds. No matter which part of the country we were in, Ted could always recognize every bird on the wing—and he knew their mating and nesting habits. He wasn’t as conversant in wildflowers, so I decided I would become the expert in that field. I spent our first years together with eyes focused earthward or with my nose in one of my many flower books, picking, pressing, and identifying every new one I found. Within three years I had hundreds of them mounted, some very rare, and as we rode our horses through the ever changing landscapes I relished being able to identify them for him. I had found a wonderful way to do “my thing” within the context of Ted’s life.

Another creative project I took up was photographing his properties. I wanted to become deeply familiar with all of them, so I decided I would try to capture the essence of each one and then create albums called

Homes Sweet Homes

for Ted and each of his children. Within a few years, as the properties began to expand in number, what I thought would be a one-album-per-person job became a five-album-per-person travail.

Every one of my projects caused friction with Ted. He felt abandoned, said it was a way for me to avoid intimacy (he was partly right), and called me a workaholic—while I thought of myself as needing a creative outlet and felt, as Mark Twain once said, that “really a man’s own work is play and not work at all.” I tried hard to understand Ted’s neediness, so I’d reluctantly cut back. But I refused to give up my pastimes entirely, especially since (unbeknownst to him, or to me at the time), I had given up things far more important. Like my voice.

T

ed is the only person I know who has had to apologize more than I have. He has apologized to Christians, Catholics, Jews, African-Americans, the antichoice people, and the pope. He’s an equal opportunity offender. He can’t help himself; like a child, he often seems at the mercy of his impulses. It’s a rare occurrence when something enters his head that doesn’t come out of his mouth.

Like the time he was making a very important appearance at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. Time Warner was represented on the Turner board of directors and was preventing Ted from buying a major broadcast network to add to his cable empire, and he felt this would keep him from competing with other media conglomerates like Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp, Disney, and Viacom. At the same time he was in major negotiations on a TBS merger with Time Warner: One false move and everything could fall apart. I was too nervous to sleep the night before. Not Ted. As usual, he hadn’t prepared and had made no notes; but like his hero Alexander the Great, he always slept well on the eve of battle.

On the day of the speech all the journalists who packed the hall were aware that it was a precarious time. So imagine their shock (and mine) when in the midst of the speech he said, “Millions of women have their clitorises cut off before they are ten or twelve years old, so they can’t have fun in sex. . . . Between fifty percent and eighty percent of Egyptian girls have their clits cut off. . . . Talk about barbaric mutilation . . . I’m being clitorized by Time Warner.” Some people laughed; others were too stunned. Many looked over at me. I simply slid down in my seat.

Hey, it wasn’t my idea.

Several years later Ted would give an unprecedented $1 billion to establish the United Nations Foundation. Over the years many large grants from the foundation have gone to stop FGM (female genital mutilation). You can’t say he doesn’t put his money where his mouth is.

C

ertainly the most public part of my new life with Ted was our attendance at the Braves games. In the fall of 1991, right before we got married, the Atlanta Braves played in their first World Series. I can’t remember ever being on such a protracted adrenaline high or so superstitious: If I had a Band-Aid on my index finger during a winning game, I’d make sure it was there for the next one. Same with underwear, earrings, and caps. I began a personal collection of winning Braves caps that people gave me, and for the Braves’ victorious 1995 World Series, I was wearing my all-time good-luck black-and-white coat made from bison hair. Plenty of things he’d done in his life justified his celebrity, but none guaranteed Ted’s standing as folk hero to Atlantans like his having stuck with the Braves and brought home a winner.

D

uring the first year of our going steady, besides traveling with the team during baseball season, we crisscrossed the globe constantly, visiting the Soviet Union, Europe, Asia, and Greece as Ted’s various undertakings demanded his presence. I had been in many of the places before and had had my own experiences there, but being on the arm of Ted Turner made it different. With a few noticeable exceptions the spotlight was always on him. He was the one who did the speaking and was feted and celebrated, and although people at CNN used to say that I was the first woman in Ted’s life who had a talking role, it was definitely a supporting one. Sometimes I would feel invisible and frustrated, as when he would give a speech about something that was important to both of us without having prepared and would, in my opinion, end up rambling.

Occasionally, though, the tables were turned, like the time we met with President Mikhail Gorbachev in his office in the Kremlin. During the half hour the three of us spent together, the president spent a good chunk of our time talking to me. As we left Ted whispered, “You know, that was a very unusual situation for me.”

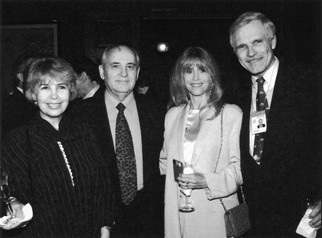

Ted getting carried away during “Auld Lang Syne” at the start of a Braves game. Left to right: Nancy McGuirk, Ted, me, President Carter, Jennie Turner, over the president’s shoulder, and Rosalynn Carter with her back turned.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

1995 in San Francisco at the State of the World Forum with President Mikhail and Raisa Gorbachev.

(AP/Wide World Photos)

“It’s not easy, is it?” I replied. “I know. I feel like a tagalong all the time these days and I’m not used to it, either. I’m willing to settle into this new role, but it must be hard when it happens to you, too.”

Fortunately we were getting better at talking about our feelings, so instead of pouting or pretending it hadn’t happened, Ted was able to regale listeners with the story of how he had spent twenty-eight minutes staring at Gorbachev’s back.

I was learning a valuable lesson: When you confront problems and work them through, what might have been a rupture becomes stronger at the broken place. It is analogous to bodybuilding: When you lift weights to build muscle, you cause microscopic tears to occur in the muscle tissue, and when the tears heal (it takes forty-eight hours) the torn places become stronger. Still, much of me remained a handmaiden to my insecurities. My long-standing fear of not being good enough kept me feeling that if he knew me fully, he couldn’t possibly love me. What this meant was that I was willing to forfeit

my

authenticity to be in a relationship with

him.

Often at business receptions I would stand silently by Ted’s side, listening to men in the highest echelons of power discuss how much better things were in, say, Brazil or some other less-developed country I had visited, and I would think, Haven’t they seen the favelas? The slums? People see what they need and want to see. I realized that these men, these makers of policy, designers of structural adjustments, and rationalizers for conflict, cannot allow themselves to see any consequences of their policies that might shake their certainty that they are doing the right thing. The bar girls, the boys and girls who prostitute themselves to feed their families, the women who earn $1 a day in U.S. maquiladoras in Mexico, the desperate gangs of youth, the garbage pickers, the displaced farmers—these brutal realities pass under the radar of liberal academe, of the economists and social scientists who sip their champagne and praise themselves about the great job they’ve done in Central and South America, or wherever.