My Life So Far (83 page)

Once again I seemed to have become someone new because of a man. But beneath the surface I felt a continuity in core values. With Ted I felt I could achieve the true, deep soul connection that had eluded me. Ted was not intimidated by me. I loved him. I loved his smell, his skin, his playfulness, his worldview, his transparency—and I knew that I was finally ready to do the needed work on myself to overcome my fear of intimacy. I wanted this to work and I was prepared to put some parts of myself (moviemaking, mostly) to bed, believing that other parts (my heart) would be waking up. Ultimately I was right, though it didn’t end up the way I thought it would.

My fear of intimacy had yet to be conquered, so I wasn’t able to see that Ted himself wasn’t capable of really showing up in a relationship. I didn’t even notice his absence until I began to heal myself. Still, I

did

heal, and I learned so much from Ted on so many levels that I don’t regret throwing myself wholeheartedly into trying to make it succeed. Even so, there were days when I was overcome with the feeling that I was making a big mistake and could lose my children and my life.

Nonetheless, I sold my home in Santa Monica as well as Laurel Springs Ranch, packed my belongings, moved all my furniture into Ted’s various houses, and migrated south.

I’d never been in the South long enough to get to know it, and immediately I was struck by people’s friendliness. Never in all my travels had I been in a place where people came up and said, “Welcome, we’re so glad you’re here.” I knew, of course, about the political conservatism. And some of Ted’s acquaintances were less than happy about my appearance on the scene. Ted would say, “Jane was right about Vietnam. I was wrong.” He was ready to stand beside me.

The South took some adjusting to. It forced me to slow down, shift gears, and pay close attention. There were so many otherances: the yes-ma’am-no-sir culture, for instance.

My women friends in the West had been feminists; their relationships with their partners were democratic—shared child care, housekeeping, and cooking, working outside the home, holding independent political opinions. Therefore I was surprised at what I first perceived as subservience, a high importance placed on tradition and propriety among many southern white women. (I found this

not

true of most of the black women I met, perhaps because, from childhood, many black women have been taught that they have to take care of themselves.) As I got to know them, however, southern white women turned out to have plenty of starch in their spines, much more than had been apparent at first blush, and I have, over time, given much thought to why there is that misleading first impression.

The South was an agrarian culture for much longer than the industrialized North: Families lived on farms, some on plantations; it was a culture of property, including humans

as

property. The institution of slavery condoned one

race-

based group of humans serving as commodities to enhance the social and economic power of the other. This made the

gender-

based subservience

within

the patriarchal family seem more normal and acceptable. Add to this the fact of living in isolated rural communities, where it was difficult for women to know there was any other way and no place to go to if they were cast out because of their uppity behavior. Church life was the South’s central social outlet, and there, too, hierarchy and conformity rule. Seeing it from this historical perspective made it easier for me to embrace my less uppity southern women friends.

One more obvious difference:

church.

In California, the only people I knew who regularly went to religious services were my Jewish friends. Now, suddenly, I was getting to know—and like—smart, progressive, funny, not-uptight practicing Christians. Some were not famous; some were—President Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter, Ambassador Andy Young, and others with whom my relationship with Ted brought me in regular contact.

I was still experiencing a feeling of being “led”—watched over—but I viewed it as a secular phenomenon, and the deep faith of my new friends was a source of fascination to me.

Could it be,

I wondered,

that what is leading them is what is leading me?

Whenever I was with my Christian friends, I would always ask them questions about their faith.

N

ot since my early years in Greenwich, Connecticut, had racial issues been so much in evidence as when I moved south, though I don’t know to this day whether there actually

is

more racism in the South. It may just be more hidden elsewhere. Early on, Lulu (who is dark-skinned) made me aware of differences in

how

racism in the South has been internalized by African-Americans. Asked how she felt about living in Atlanta (where she moved a few years after I did), she said, “I have felt more discriminated against by

blacks,

especially light-skinned blacks, down here than I ever did by whites in the North.”

A

n important part of the new world that I stepped into were Ted’s five children: Jennie, the youngest, was a student at Georgia State; Beauregard (Beau), the youngest of the three boys, was in his second year at the Citadel in South Carolina; Rhett, the first child from Ted’s second marriage, to Janie Smith, was a cameraman with CNN in Tokyo; Teddy, the eldest son from Ted’s first marriage, to Judy Nye, was working with a country music cable network; and Laura, the firstborn, ran her own clothing store in Atlanta’s fashionable Buckhead district and had just started dating a man with the wonderfully southern name Rutherford—Rutherford Seydel II—whom she would soon marry. I’m glad that I came into Ted’s life in time to see two of the children graduate, all of them marry, have babies, and grow into adulthood.

Side by side with President Jimmy Carter at a Habitat for Humanity blitz in Americus, Georgia.

(Julie Lopez/Habitat for Humanity International)

Janice Crystal took this picture of Ted and me at the Flying D while she and Billy were visiting.

(Billy and Janice Crystal)

Like their father, they are survivors of complicated childhoods, and I grew to admire and love each of them for how they have coped and matured.

Because of the important role Susan had played in my adolescence, I knew how to be a stepmother, and saw right away that one important thing I could do was help bring Ted closer with the children. The five of them love and admire their father and embrace his values.

Ted embraces differences; he believes in putting his arms around everyone, including people with whom he doesn’t agree. He would say to me, “You catch more bees with honey than with vinegar.” I watched him practice what he preached and saw people change as a result.

I

changed as a result. I have met and become friends with conservative Republicans and Christians I would never otherwise have taken the time to get to know; I would thus have missed seeing the common humanity beneath the surface differences.

I’m someone who loves learning new things and facing challenges, and there were plenty of those in the new life I’d chosen. Besides Ted’s humor, sex appeal, and intelligence, he was offering me Paradise. Most of our time together, especially in the beginning, was spent on his various properties, riding, fishing, hiking, and exploring. Back then the properties numbered five, not counting Atlanta, and just as you start a jigsaw puzzle with the corners and edges, his “starter properties” ranged from his coastal island off South Carolina to Big Sur on the other edge, with Montana at the top. By our third year together, he had begun filling in the middle—two more in Montana, three in the Sand Hills of Nebraska, two in South Dakota, and three in New Mexico, one of which includes an entire mountain range, the Fra Cristobal just to the east of Elephant Butte Reservoir. Vermejo Park Ranch, on the northern border of New Mexico near Raton and overlapping into Colorado, comprises almost 600,000 acres—the largest privately owned, contiguous piece of property in the United States, nearly as large as Rhode Island (it starts in the Rockies and ends in the Great Plains). Besides these, Ted has two spectacular properties in Patagonia and one in Tierra del Fuego, for a total of something in the neighborhood of 1.7 million acres.

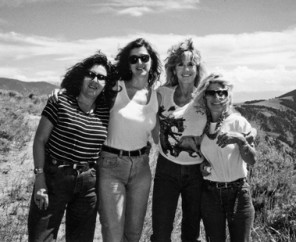

Left to right: Lois Bonfiglio (my producing partner after Bruce), Paula Weinstein, me, and Becky Fonda—visiting me on the Bar None Ranch.

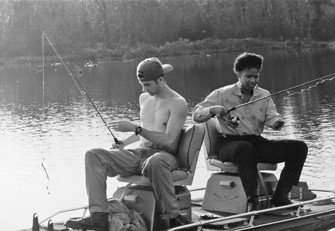

Troy and Lulu bass fishing at Avalon Plantation.

Once he got started with his bison, Ted decided to grow his herd for commercial purposes, knowing that this once almost endangered animal would never become more than an exotic trophy species in the United States unless it had market value. To grow a herd, you need to buy more land, and that was the underlying reason for most of his purchases of western ranches. At last count he had thirty-seven thousand head of bison, 10 percent of the entire U.S. herd.

The flagship ranch was and still is the Flying D, the one in Montana I told him not to buy. One afternoon Ted blindfolded me, drove me into the hills, led me out of the car, took off the blindfold, and said, “This is where we’ll build our home.” He pointed to a valley with a tiny stream running through it. “Right down there I’m going to create a lake that will reflect the Spanish Peaks. It will be our Golden Pond.” And that’s exactly what he did. He did the lake and I did the house. I wanted us to have at least

one

home that reflected me, with a ceiling under which no one before me had made love with him.

Hardly a day went by that Ted and I weren’t riding over the Flying D’s wide expanse of rolling green hills, through forests of aspens and herds of elk, hundreds at a time. By now I had brought my three horses from Laurel Springs Ranch: two Arabians and a palomino. I like riding Arabs—they’re hot-blooded, all nerves, heart, and endurance, like Ted. You can feel their spirit under you.